Assessing Environmental Attitudes under China’s Accelerating Ecological Civilization: A Case of the Urban Green Infrastructure Project in Zhangjiagang Bay

Publication: Journal of Urban Planning and Development

Volume 149, Issue 4

Abstract

The planning and management of urban green infrastructure (UGI) are at the forefront of global biodiversity conservation. Building an environmental consensus rooted in environmental ethics and values is pivotal to the lasting success of UGI projects. Reflecting the specific classification into ecocentrism–anthropocentrism and Kellert’s typologies and the theoretical connections between environmental ethics and ecological civilization, this study upgrades the adapted ecocentric and anthropocentric attitude toward the environment (AEA) scale accordingly to assess environmental attitudes and applies it in a survey of the main stakeholders involved in Zhangjiagang Bay Eco-Park, an ecological restoration project in China included in the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDGs) Good Practice list. The paper unveils the diverse hidden value patterns of stakeholders and suggests new measures for sustainable UGI management. The authors argue that the AEA scale adapted and tested in this study connects well with the theories of environmental philosophy and is proven with good reliability, strong explanatory power, and potential value for UGI planning and management.

Practical Applications

In the policy-driven fields of urban practice, consensus building is one of the most important but, at the same time, most difficult processes to achieve. Without a good understanding of the diverse environmental perspectives of stakeholders, urban planning projects often die prematurely or gradually fade out due to unsustainable implementation or management in the long run. Drawing from the theoretical progress in environmental ethics, the authors adapted an AEA scale with two-tiered subscales that could indicate the general orientation on the spectrum of anthropocentric to ecocentric attitudes and reveal the specific motivations behind behaviors for better practical policy implications. The results of this case study indicate an overall weak-anthropocentric orientation and, more specifically, show the internal value conflicts of local officials and the significance of naturalistic and moralistic perspectives for the public. This study also pinpoints the value and urgency of ongoing environmental education on important ecological issues to enable the public to genuinely embrace the policy of ecological civilization that is currently imposed from the top down. With its strong power to explain value orientation, this AEA scale could be used to facilitate stakeholder participation from the bottom up and a process of crafting and communicating urban planning and management policies while building consensus.

Introduction

Urbanization places one of the greatest threats to global biodiversity (Seto et al. 2012). Urban green infrastructure (UGI) is considered a novel ecosystem in cities (Pickett et al. 2001) and is playing an increasingly important role in global biodiversity conservation, particularly through planning, design, and management (Aronson et al. 2017). The key challenge in UGI conservation, design, and management is to balance human perceptions and needs with the ecological requirements to preserve and enhance biodiversity (Aronson et al. 2017). The priority that it places on conservation planning and design is subject to social, cultural, and economic factors (Aronson et al. 2017), which is never an easy process to reach a consensus. Without a good understanding of the diverse environmental perspectives of the stakeholders, UGI projects often die prematurely or gradually fade out due to unsustainable implementation or management in the long run (EPA 2022; Hagemann et al. 2020; Thorne et al. 2018; Zuniga-Teran et al. 2020). The imminent and pivotal first step to success lies in environmental consensus-building rooted in the belief in environmental ethics and values (Parris et al. 2018).

Research relevant to environmental ethics and values remains primarily focused on the growing theoretical complexity of its classifications (Chang et al. 2011; Cocks and Simpson 2015; Thompson and Barton 1994) and does not fully translate this progress into the urban applied fields. The nature of UGIs provides potential in both ecocentric and anthropocentric perspectives in environmental ethics (Hagemann et al. 2020; Thorne et al. 2018; Zuniga-Teran et al. 2020). For this reason, UGIs are an ideal scenario to test the practical application of theoretical classifications using suitable environmental-attitude assessment tools (Hagemann et al. 2020; Thorne et al. 2018; Zuniga-Teran et al. 2020). Meanwhile, the Chinese resonant philosophy of ecological civilization shares the same theoretical roots of process philosophy with environmental ethics (Wang et al. 2020) and is widely acknowledged in both government and research circles in China. For this reason, the authors selected the Zhangjiagang Bay (ZJG Bay) Eco-Park project in the Yangtze River Delta of China, which is included in the UN’s SDG Good Practice list, as a UGI case study site.

This paper starts with a review of the literature to understand the interconnected relationship between environmental ethics and China’s top-down ecological civilization policies and the theoretical progress of the environmental assessment tools and their applications in UGI projects. This is followed by the discussion of implementing the UN’s SDG listed Good Practice of ZJG Bay Eco-Park project under the ecological civilization in China. Next, the authors examine different environmental attitude assessment tools and adapt the selected tool. Finally, the authors present the survey data of ZJG Bay Eco-Park, discuss the results, and draw conclusions based on the findings.

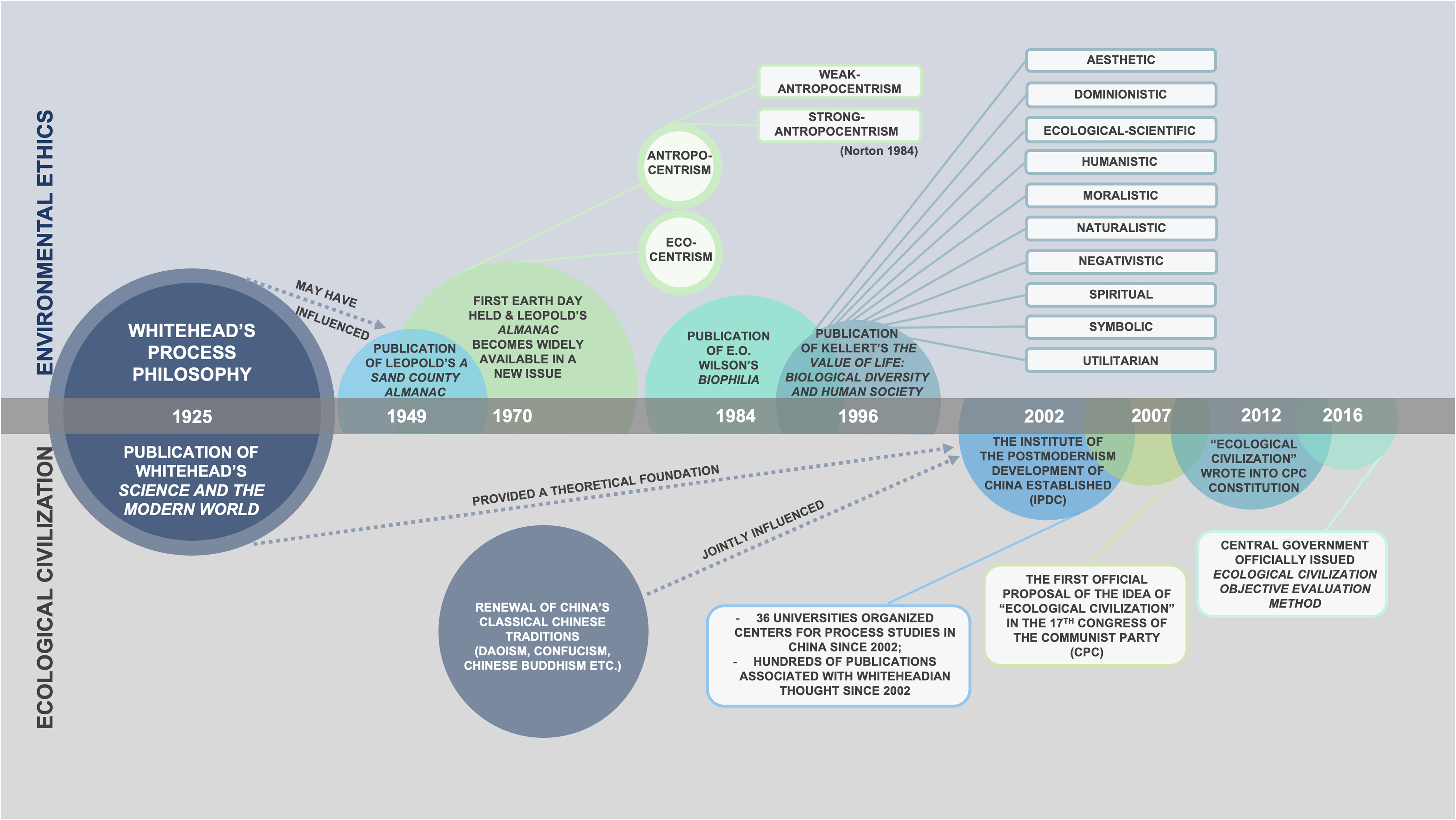

Environmental Ethics and Their Relationship with China’s Ecological Civilization

Whitehead’s philosophy anticipated the development of environmental ethics and may have influenced Leopold’s The Land Ethic from 1970 (Callicott 1980; Henning 2016). He is widely considered to be the founding father of environmental ethics. This means that process philosophers were the key contributors to the seminal discussions that constituted the field of environmental ethics (Henning 2016) (Fig. 1). In the view of pioneering environmental philosophers, there is no ethic in environmental ethics unless it recognizes the intrinsic value of the nonhuman (Cocks and Simpson 2015; Leopold 1949). Therefore, in the early discussions that constituted the field of environmental ethics, there were two major perspectives: ecocentrism, which celebrates the intrinsic value of nature, independent from its direct value to human beings (Cocks and Simpson 2015), and anthropocentrism, in which the nonhuman environment is measured by its tangible and intangible value to human beings (Norton 1984). Later, researchers started to further divide the anthropocentric perspective into strong anthropocentrism and weak anthropocentrism (Cocks and Simpson 2015; Norton 1984). In strong anthropocentrism, the nonhuman environment is considered to be a commodity or merely an object of use, while the weak anthropocentrism perspective measures the natural environment by its value to human beings, but the value is significantly expanded beyond the commodities associated with strong anthropocentrism (Cocks and Simpson 2015). Further, the biophilia hypothesis boldly asserts the existence of a biologically based innate human need to affiliate with life and lifelike processes. Wilson (1984) and Kellert (1996) refined a typology of environmental values that reflects a range of physical, emotional, and intellectual expressions of the attitudes toward nature, such as utilitarian, naturalistic, ecologistic-scientific, aesthetic, symbolic, humanistic” moralistic, dominionistic, and negativistic environmental valuations.

Almost a century later, Chinese intellectuals have been attracted to the philosophy of Whitehead, who called his thought the philosophy of organism (Henning 2016; Wang et al. 2020; Whitehead et al. 1978). Whitehead’s thoughts on process philosophy not only provided them with a theoretical foundation (Fig. 1) to shift from the celebrated achievement of modernism and economic growth in Chinese society to the more cutting-edge thought on the European postmodernism and also to the fulfillment of the dual commitments of the Chinese Government of ecological civilization and scientific ways of thinking. It joins the recent revival of traditional Chinese wisdom with China’s environmental movement (Wang et al. 2020). China has welcomed Whitehead’s thought and sees it as a way of clarifying and supporting the commitment to an ecological civilization, which has been strongly re-emphasized by President Xi (Wang et al. 2020).

Since 2007, China has continuously demonstrated its commitment to a much more harmonious relationship with the environment (Wu and Wallace 2014). There is plentiful evidence in this regard. The Communist Party formally drafted the goal of becoming an ecological civilization into its Constitution in 2012. Thirty-six universities have organized Centers for Process Studies in China, and Wang et al. (2020) documented hundreds of publications associated with Whiteheadian thought on ecological civilization since 2002. It has also launched a series of national and regional ecological-oriented mega-planning projects.

Despite US propaganda, which often criticizes China’s commitment as halfhearted (Wang et al. 2020), the real question appeared to be centered on whether the interest in the ecological civilization is solely a top-down process of the political leadership imposed on the people or is embraced and actively responded to by all levels of decision-makers and the general public in China. There is a lack of research from the bottom-up perspective to answer this question: are decision-makers at different levels also fully on-board in terms of the commitment to pursuing ecological civilization? The analysis of this information is very relevant because it is important to provide useful preliminary steps for understanding and influencing behavioral changes.

Environmental Assessment Tools and Their Applications to UGIs

A growing number of researchers have pointed out the pivotal practical values of environmental ethics theoretical classifications (Chang et al. 2011; Cocks and Simpson 2015; Thompson and Barton 1994) and have developed a variety of scales to assess environmental attitudes since the 1970s (Dunlap and Van Liere 1978; Maloney and Ward 1973; Weigel and Weigel 1978). Among all, the New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) scale has been recognized as the most well-known and widely applied scale because of its relatively high reliability and generality (Dunlap and Jones 2002; Hong 2006; Hong and Fan 2016; La Trobe and Acott 2000; Lalonde and Jackson 2002; Stern et al. 1995). It was first introduced in China by Hong (2006) and later became popular in Chinese academic circles and was applied broadly to environmental education and conservation behavior as well (Chang et al. 2011; Luo and Deng 2008; Wu et al. 2012; Wu and Zhu 2017; Yu 2014). With its broad scope, the NEP scale touches on diverse environmental theories and topics, such as anthropocentrism, human exceptionalism, ecological equilibrium, and so on. This tool is effective at capturing the environmental worldview but falls short of explaining the strong links between attitudes and actions (Thompson and Barton 1994; Wu and Zhu 2017). Ecocentric and anthropocentric individuals may, although not always, express positive attitudes toward environmental issues, with the difference in these two orientations translating into action that is absent from the NEP scale (Cocks and Simpson 2015).

In this regard, Thompson and Barton (1994) operationalized the Ecocentric and Anthropocentric Attitude toward the Environment (EA) scale and found that ecocentric attitudes were significant predictors of both self-reported and observed behaviors even after controlling for a traditional measurement of environmental attitudes. Later, Røskaft’s (2007) team in Norway used this EA scale to evaluate the belief–attitude relation among sheep farmers, wildlife managers, and research biologists toward carnivores. The results suggested that environmental beliefs might transform ecocentric values into negative or positive attitudes toward one specific environmental category based on the cognitive hierarchy model. Furthermore, Kopnina and Cocis (2017) adjusted the EA scale to better fit the field of environmental education, with a specific connection to sustainable development aims, and tested it on three groups of students in different majors. The results demonstrated that different environmental attitudes result in variations in motivations and choices of conservation behavior. For instance, ecocentric individuals are more likely to act on proenvironmental attitudes and engage in conserving behaviors. Typical examples of this can be found in environmental organizations.

Along with theoretical progress in environmental ethics, researchers continuously specify the typologies in environmental perspectives (Callicott 1992; Kellert 1996; Norton 1984, 1995). Inspired by Kellert’s environmental value typology (Diehm 2012; Kellert 1996; Wilson 1984), Delavari-Edalat and Abdi (2010) developed the Biophilia Tendency (BT) scale and conducted a survey on the two ethical groups of Asia and White British in an urban park in the United Kingdom, finding differences in negativistic, moralistic, and naturalistic values. Unlike the NEP and the EA scales, the statements in the BT scale focus specifically on talking about the perspectives toward trees. Perhaps partly due to its narrow focus, the BT scale is not used as widely as the other two. However, the detailed differential classifications based on the theoretical typologies of the BT scale make it possible to raise these environmental value distinctions to the conscious level, which helps understand the underlying motivations, which is particularly important in the applied fields of UGI planning and design, where environmental behaviors are constantly taking place.

UGI is urban green spaces that contribute to the biodiversity and conservation of ecosystems and the welfare of the population by forming part of a network of spaces that connect the city and nature (Cameron and Blanuša 2016). Since this requires a long-term environmental commitment and problem-solving in a complex environment, the planning and design of UGIs are highly relevant to the influence of different environmental attitudes. Previous studies have indicated its pivotal practical values in the realm of environmental education and the promotion of outdoor conservation programs (Chang et al. 2011; Cocks and Simpson 2015; Thompson and Barton 1994) by using different environmental attitude assessment tools. Some researchers have also begun to investigate the environmental perspective of UGIs of users after the fact (Chang et al. 2011; Luo and Deng 2008), but their orientations at an early stage that shapes the implementation process have not yet been assessed (Parris et al. 2018). It also calls for appropriate environmental orientation tools that can be applied to UGIs to proactively assess these orientations. On the one hand, such tools should better reflect the progress in increasingly more specific theoretical ethical classifications. For instance, it might work better to further differentiate strong-anthropocentric and weak-anthropocentric orientations on the EA scale to apply the theoretical progress in the urban-applied field of UGIs. On the other hand, to improve the policy implications of environmental assessment, which is particularly important in the practical fields of UGIs, tools should be better able to explain motivation and provide more detailed environmental perspectives. The BT scale, originally designed for detailed attitudes of trees, is a winner in this regard. To sum up, an early conscious understanding and evaluation of underlying attitudes can help craft messages tailored to different environmental perspectives and establish a consensus amid the constant conflicts between growth and protection over time, facilitating more constructive behaviors, careful maintenance, and long-term sustainable successes (Zuniga-Teran et al. 2020).

ZJG Bay in China: UN-Listed SDG Good Practice

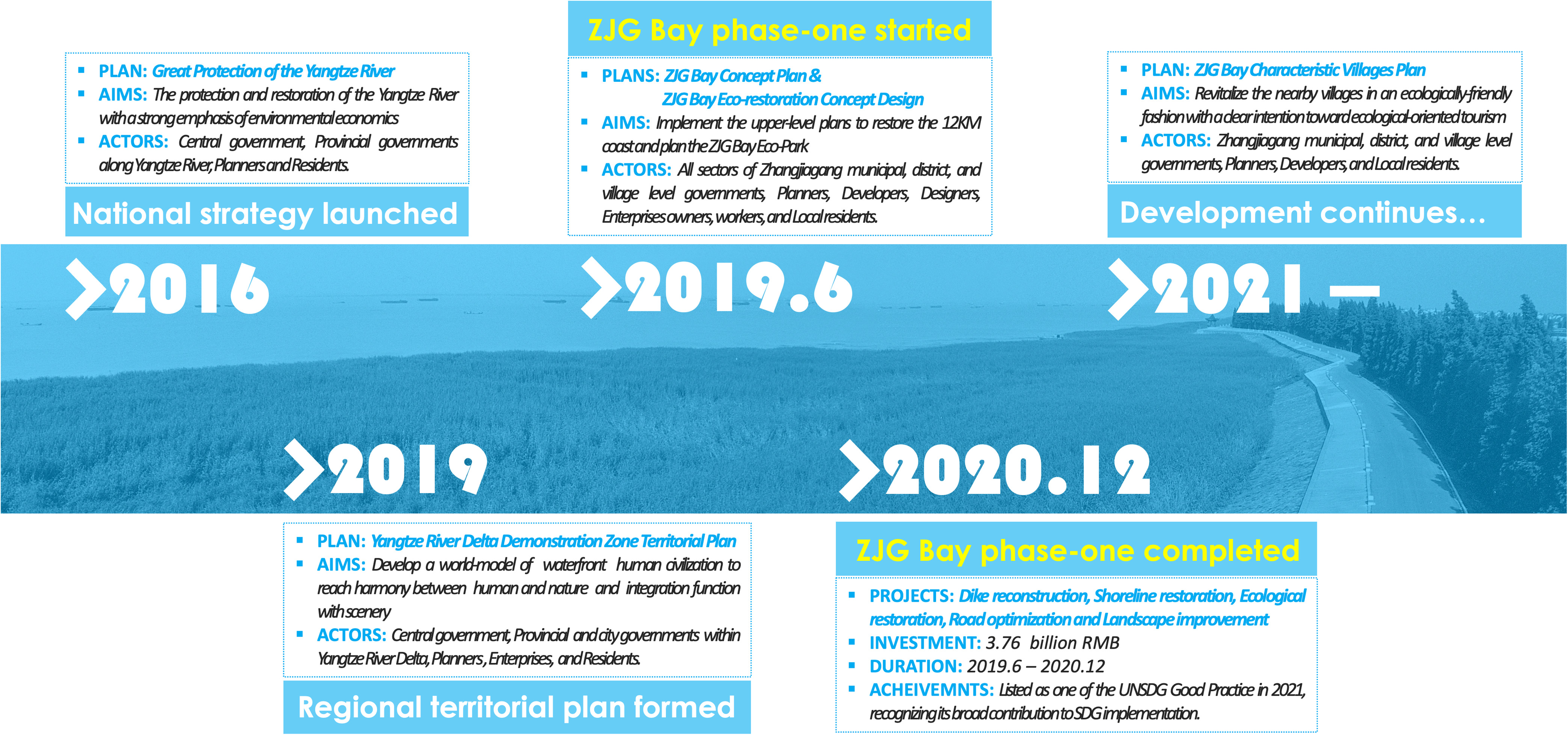

Following the imposed national strategy of ecological civilization, ZJG Bay Eco-Park was initiated by the local government as part of the ongoing mega UGI projects along the Yangtze River that involve collective efforts by different sectors and that are in different phases spread over a long period (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Timeline of ZJG Bay Eco-Park project planning and implementation.

(Image by Jing Lu.)

There are two main merits of studying the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project in this study. First, under the natural protection strategy and local government initiation, this large-scale project involves multiple critical aspects of removing polluting industries, restoring the ecological landscape, building green infrastructure, maintaining biodiversity, and ensuring public access to the eco-park (Fig. 3). Subject to a variety of consultations and collaboration with fishing farms, semioperational port enterprises, villages, local grassroots volunteer groups, professional planners, and construction companies (United Nations 2021), the project is ideal for studying the environmental perspectives of stakeholders at an operational level and for assessing the extent to which it aligns with the central government’s position on the ecocentrism–anthropocentrism spectrum and its impact on the project.

Second, implementing the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project will require tremendous effort in a complex and dynamic process, without guaranteeing long-term sustainable success. In other words, although being recognized as UNSDG Good Practice in its initial phase consolidates the results of its ecoactions, it still remains to be seen whether the project will continue its good practice to promote sustained effects. Right now, it presents a fleeting opportunity to understand the environmental perspectives of those who have contributed to the success of stage one of the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project, as well as the potential areas that are worth looking into and that could provide insights into the actions in its later stages. In this sense, the proactive nature of this study sets it apart from the previous studies on environmental attitudes, which mostly assess UGIs after the fact, and gives it the potential to monitor and influence both the building and continuity of consensus.

Adaptation of the Survey Instrument and Data Collection

Adaptation of the Survey Instrument

Referring back to the earlier discussions on the differences in environmental attitude assessment tools, the EA and BT scales outweigh the NEP scale with regard to the potential of showing the motivations behind behaviors for better practical policy implications. Comparing the EA and the BT scales, the former reflects a general orientation on the spectrum of anthropocentric to ecocentric attitudes, and the latter differentiates more detailed perspectives, which are particularly applicable to UGIs. As a result, the authors decided to adapt a new scale by incorporating both the EA and the BT scales to create a two-tier assessment tool. Since the statements in the EA scale are more universally applied than those of the BT scale, the authors mainly used the statements from the EA scale and incorporated some of the statements from the BT scale where needed. By simultaneously assessing the stakeholders' attitudes on both the EA and BT scales, as opposed to the original EA scale, the newly adapted EA scale will be able to assess both general orientation and specific typologies. For this reason, this paper refers to the adapted EA scale as the AEA scale. There were four steps in the process of adapting the AEA scale:

1.

Upgrade the EA scale to four subscales: To better reflect recent theoretical advances and societal changes, the authors further specify the strong anthropocentric and weak anthropocentric viewpoints in the EA scale according to the definitions outlined in Cocks and Simons’ (2015) study. This resulted in the four subscales of Ecocentrism, Weak Anthropocentrism, Strong Anthropocentrism, and Apathy in this upgraded EA scale (Table 2).

2.

Incorporate BT statements: Since there are only two original statements that relate to weak anthropocentric values in the existing EA scale, more statements in this subscale were needed, so the authors incorporated adapted statements from the BT scale. The authors selected the ecologistic and moralistic tendencies in addition to the utilitarian, negativistic, dominionistic, and naturalistic typologies already embedded in the EA scale. This adapted version now has six major subscales of the BT scale originating from Kellert’s (1991, 1996) typology definition listed in Table 1.

3.

Optimize the total number of statements: Previous researchers operated 22–33 statements of the EA scale in their questionnaire (Kaltenborn and Bjerke 2002; Kopnina and Cocis 2017; Thompson and Barton 1994). To optimize the length of the AEA scale and to balance out the statements in each subscale, the authors decided to add three adapted statements related to weak anthropocentric values from the BT scale and made it all-together five statements for the weak anthropocentric subscale, and consequently, the total number of statements add up to 20 with an equal number of five statements in each of the four EA subscales. A further statement selection procedure was carried out based on the criteria of “common selections among past researchers,” “diversity in environmental value tendencies,” “no ambiguity in definitions,” and “cultural relevance to China.” The conciseness of the final AEA scale makes it easier to apply in practice. The full statements and their association with the subscales are outlined in Table 2.

4.

Finalize the scale and adapt it to the Chinese version: Each statement in this AEA scale is assigned with the Likert scale from 1 to 5 selection options denoting strongly agree (1), agree (2), neutral (3), disagree (4), and strongly disagree (5). The full AEA scale was then translated into Chinese following the procedures of forward and backward translations to ensure the quality of the adapted Chinese version.

| Typologies | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Ecologistic | Interest in the ecological value of species and their relationship to the environment |

| Moralistic | Opposition to cruelty and harm toward species |

| Naturalistic | Interest in direct outdoor recreational contact with species |

| Utilitarian | Interest in the utilization of the species or subordination of their habitat for the practical benefit of humans |

| Negativistic | Fear, dislike, or indifference toward species |

| Dominionistic | Interest in the mastery, control, and dominance of the animals |

Source: Data from Kellert (1996).

| No. | Statements | Scales | Mean scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA scale | BT scale | Officials | Professionals | Residents | F-values | p | ||

| 1 | One of the worst things about overpopulation is that many natural areas are being destroyed for development | Eco | Ecol | 1.770 | 1.837 | 1.840 | 0.731 | 0.393 |

| 2 | We have a duty to save woodlands for the sake of all human beings | Weak-A | Moral | 1.070 | 1.033 | 1.160 | 2.616 | 0.107 |

| 3 | I enjoy walking in nature because I am amazed at and enjoy the individuality of beauty of trees and flowers | Weak-A | Natur | 1.110 | 1.077 | 1.210 | 4.616 | 0.033** |

| 4 | The worst thing about the loss of the rain forest is that it will restrict the development of new medicines | Strong-A | Util | 1.790 | 1.827 | 1.860 | 1.027 | 0.312 |

| 5 | It seems to me that most conservationists are pessimistic and somewhat paranoid | Apathy | Neg | 2.730 | 2.857 | 2.600 | 0.780 | 0.378 |

| 6 | I prefer wildlife reserves to zoos | Eco | Ecol | 1.350 | 1.637 | 1.660 | 1.007 | 0.316 |

| 7 | I do not think the problem of depletion of natural resources is as bad as many people make it out to be | Apathy | Neg | 3.210 | 3.633 | 2.870 | 4.877 | 0.028** |

| 8 | The thing that concerns me most about deforestation is that there will not be enough lumber for future generations | Strong-A | Util | 2.450 | 2.290 | 2.130 | 2.129 | 0.146 |

| 9 | I love being out in nature to find comfort when I am unhappy | Weak-A | Natur | 1.680 | 1.393 | 1.470 | 11.690 | 0.001* |

| 10 | Most environmental problems will solve themselves given enough time | Apathy | Neg | 2.340 | 2.367 | 2.130 | 1.160 | 0.282 |

| 11 | I do not care about environmental problems | Apathy | Neg | 4.440 | 4.583 | 4.520 | 1.104 | 0.294 |

| 12 | One of the most important reasons to keep lakes and rivers clean is so that people have drinking water | Strong-A | Util | 2.070 | 2.127 | 2.020 | 8.896 | 0.003* |

| 13 | It makes me sad to see natural environments destroyed | Eco | Moral | 1.140 | 1.190 | 1.240 | 1.024 | 0.312 |

| 14 | The most important reason for conservation is human survival | Strong-A | Dom | 1.390 | 1.343 | 1.320 | 3.907 | 0.049** |

| 15 | One of the best things about recycling is that it saves money | Strong-A | Util | 2.560 | 2.490 | 2.270 | 3.135 | 0.078 |

| 16 | I feel better about myself when I know more different type of trees and flowers | Weak-A | Ecol | 1.590 | 1.530 | 1.570 | 2.762 | 0.098 |

| 17 | Too much emphasis has been placed on conservation | Apathy | Neg | 3.550 | 3.453 | 2.960 | 0.325 | 0.569 |

| 18 | Nature is valuable for its own sake, independent of human interests | Eco | Ecol | 2.920 | 2.757 | 3.020 | 0.527 | 0.468 |

| 19 | I enjoy being out in nature because it is a great stress reducer for me | Weak-A | Natur | 1.340 | 1.367 | 1.430 | 2.349 | 0.127 |

| 20 | Humans are as much a part of the ecosystem as other animals | Eco | Ecol | 1.100 | 1.137 | 1.220 | 0.036 | 0.849 |

Source: Data from Delavari-Edalat and Abdi (2010), Kopnina and Cocis (2017), and Thompson and Barton (1994).

Note: AEA scale reliability test: Cronbach’s alpha of all variables (n = 20) = 0.76 (>0.7)

AEA scale validity test: Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy = 0.81(>0.8); Bartlett’s test of sphericity—p (sig.) < 0.01.

Officials, n = 71; professionals, n = 115; residents, n = 94.

Eco = ecocentric; Weak-A = weak-anthropocentric; Strong-A = strong-anthropocentric; Apathy = environmental apathy; Ecol = ecologistic; Natur = naturalistic; Moral = moralistic; Dom dominionistic; Util = utilitarian; and Neg = negativistic subscales.

*p < 0.01, **p < 0.05.

Sampling and Data Collection

In mid-October 2021, the questionnaire was distributed to the stakeholders listed in Table 3 using the widely used Chinese questionnaire platform WJX and received a total of 272 responses within 1 week. The breakdown of the final respondents was 26.1% local officials, 39.3% professionals, and 34.6% local residents. All of the collected data were imported into SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics versions 21 and 27) to verify the validity (Cronbach’s alpha test) and reliability (KMO and Bartlett’s test) of the adapted scale. The authors also calculated mean values by subscales and subgroups to understand the central tendency of probability distributions of each subscales and subgroups, conducted a categorical principal component analysis to analyze the relative impact of the subgroups on the subscales, and conducted a cross-subscale partial correlation analysis by group type to understand the strength of the relationship between each of the subscales.

| Stakeholders | Roles | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Local officials | Initiators | Municipal mayor offices, natural resources and planning bureau, environmental protection bureau, village committees, and so on |

| Professionals | Implementers | Urban planners, landscape architects and engineers, local volunteer groups, and construction personnel and managers |

| Residents | Influenced | The villagers and middle school students from the surrounding area, fishing farmers, and enterprise owners and employees who made their living from ZJG Bay before the establishment of the eco-park |

Data Analysis and Discussion

Data Analysis Results

The reliability of the AEA scale was acceptable, with Cronbach’s alpha values for all variables of 0.76, and the validity of the survey with KMO and Bartlett’s test was good (0.81, p < 0.01) (Table 2).

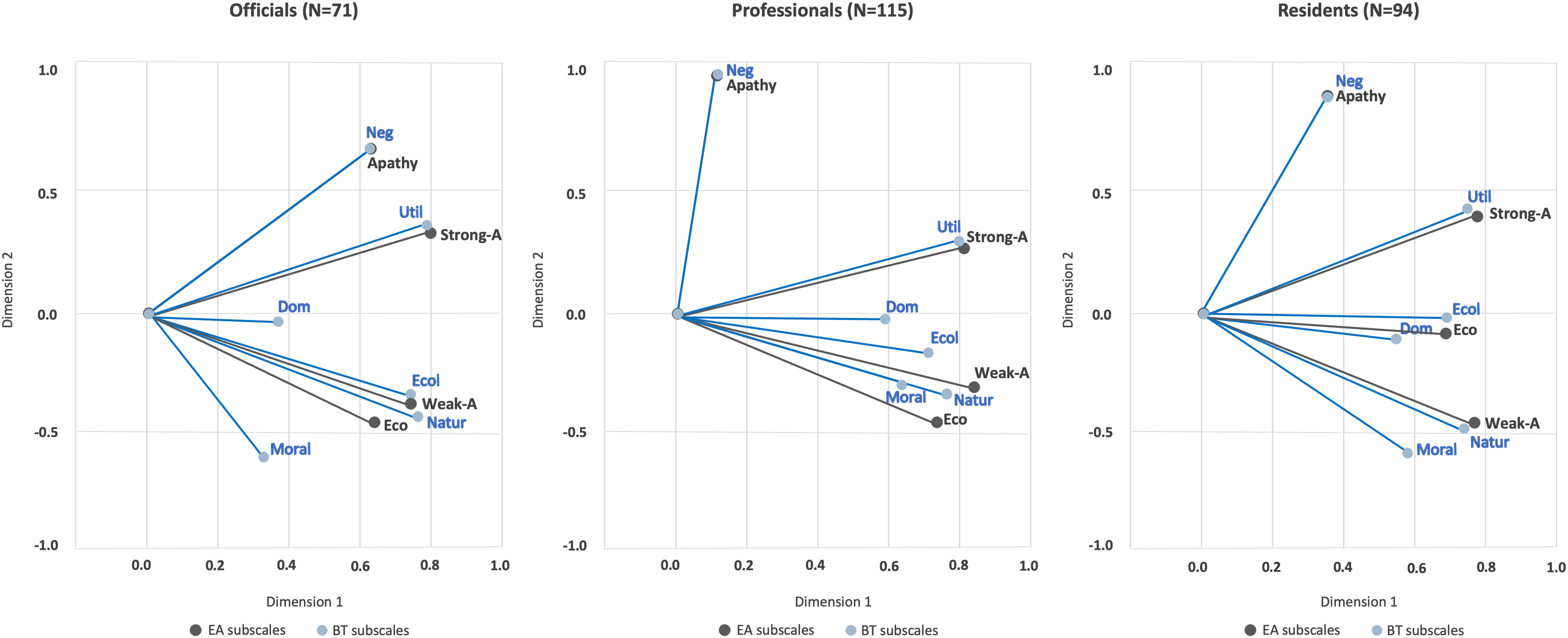

The general tendency of the stakeholders of the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project was coherent with the weak-anthropocentric orientation, considering the lowest mean value of all participants (1.33, closest to the Likert scale category of “1” as “strongly agree” to the statements) to be weak-anthropocentric (Table 4). However, strong anthropocentric orientations for all participants (Weak-A = 0.804, −0.372 and Strong-A = 0.789, 0.324) were almost equal competitors (Table 5). If we consider the EA scale as a spectrum with increasing ecocentric inclinations from environmental apathy, strong-anthropocentric, weak-anthropocentric, and ecocentric, the stakeholders in this study can be said to fall between the weak anthropocentric and strong-anthropocentric standpoints.

| Scales | Mean scores | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscales | Orientations | Officials | Professionals | Residents | All participants |

| EA scale | Eco | 1.66 | 1.71 | 1.80 | 1.73 |

| Weak-A | 1.36 | 1.28 | 1.37 | 1.33 | |

| Strong-A | 2.05 | 2.02 | 1.92 | 1.99 | |

| Apathy | 3.25 | 3.38 | 3.02 | 3.22 | |

| BT scale | Ecol | 1.75 | 1.78 | 1.86 | 1.80 |

| Natur | 1.38 | 1.28 | 1.37 | 1.34 | |

| Moral | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.20 | 1.14 | |

| Dom | 1.39 | 1.34 | 1.32 | 1.35 | |

| Util | 2.22 | 2.18 | 2.07 | 2.15 | |

| Neg | 3.25 | 3.38 | 3.02 | 3.22 | |

Note: The boldface values represent the lowest mean scores in each row. Eco = ecocentric; Weak-A = weak-anthropocentric; Strong-A = strong-anthropocentric; Apathy = environmental apathy; Ecol = ecologistic; Natur = naturalistic; Moral = moralistic; Dom dominionistic; Util = utilitarian; and Neg = negativistic subscales.

| Scales | Dimension 1, Dimension 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscales | Orientations | Officials | Professionals | Residents | All participants |

| EA scale | Eco | 0.629, −0.454 | 0.720, 0.046 | 0.657, −0.123 | 0.678, −0.191 |

| Weak-A | 0.746, −0.382 | 0.822, −0.315 | 0.772, −0.479 | 0.804, −0.372 | |

| Strong-A | 0.798, 0.324 | 0.815, 0.251 | 0.787, 0.378 | 0.789, 0.324 | |

| Apathy | 0.610, 0.688 | 0.126, 0.952 | 0.365, 0.868 | 0.317, 0.886 | |

| BT scale | Ecol | 0.748, −0.355 | 0.704, 0.019 | 0.660, −0.014 | 0.686, −0.138 |

| Natur | 0.750, −0.433 | 0.751, −0.330 | 0.731, −0.487 | 0.762, −0.387 | |

| Moral | 0.315, −0.612 | 0.630, −0.274 | 0.588, −0.578 | 0.542, −0.469 | |

| Dom | 0.360, −0.020 | 0.595, −0.037 | 0.548, −0.170 | 0.518, −0.050 | |

| Util | 0.776, 0.340 | 0.804, 0.264 | 0.763, 0.415 | 0.775, 0.360 | |

| Neg | 0.610, 0.688 | 0.126, 0.952 | 0.365, 0.868 | 0.317, 0.886 | |

Note: Eco = ecocentric; Weak-A = weak-anthropocentric; Strong-A = strong-anthropocentric; Apathy = environmental apathy. Ecol = ecologistic; Natur = naturalistic; Moral = moralistic; Dom dominionistic; Util = utilitarian; and Neg = negativistic sub-scales.

In terms of the cross-subscale orientations by subgroups, there were significant statistical correlations and rich diversity patterns (Tables 5 and 6 and Fig. 4). To begin with, surprisingly, officials with either ecocentric or strong-anthropocentric viewpoints also supported environmental apathy statements; the officials with ecocentric orientation correlated with environmental apathy and negativistic subscales (0.252, p < 0.05), which was not observed in the other two groups and was contrary to common sense (Table 6). This result was in line with officials' relatively high value of environmental apathy (0.610, 0.688) in the variable principal normalization pattern (Table 5 and Fig. 4). It revealed that local officials of the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project were possibly experiencing internal conflicts in environmental attitude values—two distinct values of ecocentrism and environmental apathy both seemed to appeal to them. Meanwhile, building on previous findings of the correlation between anthropocentrism and environmental apathy (Røskaft et al. 2007), this study indicated that officials with strong-anthropocentric perspectives had the highest correlation to environmental apathy (0.572, p < 0.01) of all stakeholder groups (Table 6). In addition, there are variations across groups, but generally, officials who acknowledged weak-anthropocentric viewpoints had the strongest correlation with naturalistic typologies (0.960, p < 0.01); the value of experiencing the natural environment appealed to them most (Table 6).

| Scales | EA scale | BT scale | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco | Weak-A | Strong-A | Apathy | Ecol | Natur | Moral | Dom | Util | Neg | |

| Officials (n = 71) | ||||||||||

| Eco | 1.000 | 0.484a | 0.305 | 0.252b | 0.944a | 0.494a | 0.465a | 0.144 | 0.295b | 0.252b |

| Weak-A | 0.484a | 1.000 | 0.405a | 0.199 | 0.655a | 0.960a | 0.400a | 0.205 | 0.390a | 0.199 |

| Strong-A | 0.305 | 0.405a | 1.000 | 0.572a | 0.359b | 0.428a | −0.113 | 0.407a | 0.982a | 0.572a |

| Apathy | 0.252b | −0.199 | 0.572a | 1.000 | 0.318 | 0.234 | −0.168 | 0.131 | 0.582a | 1.000 |

| Professionals (n = 115) | ||||||||||

| Eco | 1.000 | 0.503a | 0.275b | 0.115 | 0.977a | 0.444a | 0.287b | 0.270 | 0.291b | 0.115 |

| Weak-A | 0.503a | 1.000 | 0.362a | −0.088 | 0.531a | 0.913a | 0.634a | 0.376a | 0.329a | −0.088 |

| Strong-A | 0.275b | 0.362a | 1.000 | 0.341a | 0.291b | 0.253 | 0.323a | 0.522a | 0.991a | 0.341a |

| Apathy | 0.115 | −0.088 | 0.341a | 1.000 | 0.094 | −0.061 | −0.061 | 0.024 | 0.363a | 1.000 |

| Residents (n = 94) | ||||||||||

| Eco | 1.000 | 0.530a | 0.274 | 0.130 | 0.960a | 0.547a | 0.432a | 0.211b | 0.253 | 0.130 |

| Weak-A | 0.530a | 1.000 | 0.387a | −0.091 | 0.563a | 0.940a | 0.780a | 0.448a | 0.328b | −0.091 |

| Strong-A | 0.274 | 0.387a | 1.000 | 0.508a | 0.352a | 0.303b | 0.207 | 0.462a | 0.985a | 0.508a |

| Apathy | 0.130 | −0.091 | 0.508a | 1.000 | 0.183 | −0.127 | −0.184 | −0.084 | 0.530a | 1.000 |

Note: The boldface values are highlighted significant correlations. Controlled variables including education level, gender, age, park visit frequency, and park visit duration. Eco = ecocentric; Weak-A = weak-anthropocentric; Strong-A = strong-anthropocentric; Apathy = environmental apathy; Ecol = ecologistic; Natur = naturalistic; Moral = moralistic; Dom = dominionistic; Util = utilitarian; and Neg = negativistic subscales.

a

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tiered).

b

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tiered).

Second, the choices of professionals highly correlated to the definitions of these tendencies in both subscales, while simultaneously demonstrating diverse value orientations. For instance, professionals with ecocentric orientation scored the highest correlation with ecologistic tendency (0.977, p < 0.01), while those prone to strong-anthropocentric statements had the strongest correlation (0.991, p < 0.01) with utilitarian tendency (Table 6). Weak-anthropocentric professionals correlated to all of Kellert’s typology tendencies except negativistic ones. The variable principal normalization graph (Fig. 4) also clearly demonstrated this pattern of knowledge of professionals. Environmental apathy and negativism were the lowest (0.126) compared to the other two groups, indicating the strong proenvironmental inclinations of professionals due to their environmental knowledge (Table 6).

Finally, residents were more sensitive to moralistic statements despite having the lowest mean values toward ecocentric attitude. Residents with weak-anthropocentric viewpoints had the highest correlation with ecocentrism (0.530, p < 0.01) and had a stronger correlation (0.780, p < 0.01) to the moralistic view (Table 6). The variable principal normalization pattern not only coincided with the significance of the impact of moralistic statements on residents but also revealed that the dominionistic subscale was also relatively significant for residents. A similar pattern was also found for professionals but not for officials, whose moralistic and dominionistic components were much lower than other counterparts (Table 5 and Fig. 4).

Discussions

The adapted AEA scale, with its acceptable reliability and good validity, connects well with the more sophisticated theoretical classifications, aligns with the recent progress in environmental philosophy, and is shown to have a quality explanation and implication value for UGI planning and design. With the AEA scale better specifying the two-tier subcategories, the case study survey results of the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project effectively show the detailed environmental orientations of the stakeholders. It can further provide actionable policy implications to ensure ZJG Bay Eco-Park project’s long-term adherence to the UN SDG standards and also improve public participation and consensus-building in UGI planning and design practice beyond this study site.

First, it is important to conduct an AEA scale survey at the start of projects to better understand specific attitude orientations, which helps stakeholders understand their motivations and the motivations of others toward environmental conservation behaviors. This action would help all stakeholders to understand the underlying reasons and meaningfulness of other perspectives and facilitate consensus-building in proenvironmental actions of all sorts. In this study, conducted right after phase one of the project, we found similar standpoints for all stakeholders, with professionals slightly more prone to weak-anthropocentric than other groups. Such consensus might explain the success of phase one of the ZJG Bay Eco-Park recognized by UN SDG. At the same time, professionals working on the later phases and the long-term management of ZJG Bay Eco-Park should be aware of these differences in perspective. Of course, it would be even better, and it is suggested that future studies incorporate the AEA study findings from earlier stages to look at how the effect of these attitude differences in the long term. This is particularly important in these policy-driven urban fields, where the underlying motivations are of greater significance in creating communication and planning strategies that incorporate the desires of the different stakeholders. Urban and landscape professionals should therefore shift from their previous neglect (Parris et al. 2018) and pay more attention to the theoretical progress and practical applications of environmental ethics.

Second, by understanding the stakeholders’ tendencies, decision-makers could use multiple communication strategies tailored to their desires to motivate proenvironmental actions and improve awareness. Since the public better recognized moralistic statements that were possibly influenced by the Chinese classic philosophy of harmony of man and nature that resonates in China’s ecological civilization policies (Henning 2016; Wang et al. 2020), it makes sense to stress the importance of moralistic values while designing the policy messages to accelerate the process toward an ecological civilization, leading to greater gains with minimal effort. For instance, when framing the vision and positioning of policy actions or projects that are particularly ecological-civilization related, it might unite stakeholders more to emphasize the perspective of the moral duties to other species and the natural environment. Learning from this finding, the choice of the Whiteheadian process philosophy, which incorporates ecological civilization with Chinese classic philosophy well (Wang et al. 2020), is potentially shown to be a good choice in the sense that it is easier to reach a consensus in Chinese culture and society.

Third, the AEA scale could also inform planners and designers to better facilitate bottom-up participation from cradle to grave in the long course of planning, design, and management. Based on the results of this study, the naturalistic experience that promotes contact with nature and facilitates the nonmaterialized enjoyment of the natural space, such as psychological, mental health, aesthetics, and the like, would be best accepted by the stakeholders and should therefore be prioritized. This means that the planning, design, and management of the later phases of the ZJG Bay project could benefit significantly from research on the preferable naturalistic-oriented experience in ZJG Bay Eco-Park. By improving the sense of pleasure and increasing the possible uses of ZJG Bay Eco-Park, it would serve as a good alternative measure of environmental education provision and ecological civilization promotion. While places that rely more on volunteering from the bottom-up require consensus-building at the start and continuously throughout the process to make a project possible, evaluating attitudes is important for places like China to ensure long-term application and quality implementation.

Last but not least, in terms of long-term effects, ongoing environmental education about environmental knowledge and ecological civilization is highly necessary, particularly for government officials and residents. A better understanding of different attitudes, based on carefully designed education and publicity, can better facilitate bottom-up initiatives, ensure ongoing commitment and consensus, and foster spontaneous behaviors that reduce administrative costs. One of the more striking findings in this case study is the internal conflict of officials that was repeatedly revealed in the analysis. Such findings provide a good example that local governments and residents are made up of a complexity of different divisions and individuals that do not always share the same visions. Such complexity has been discussed in the theoretical debates in political ecology (Goldman et al. 2018; Roberts 2020). The internal conflict might be a result of suppressed waterfront development needs of the local officials, fish farmers, and semioperational port enterprise owners under the top-down state-imposed ecological civilization movements. Given the fact that the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project aims to restore the previously polluted environment, another possible explanation of such internal conflict might be due to the slow response of the locals from shifting the previous polluting practices to the more proenvironment mindsets. The specific reasons for the uneven power dynamics involving knowing and managing UGIs among state governments, local governments, professionals, and residents are still yet to be exposed with the help of follow-up qualitative studies.

However, what we can derive from current findings are that some of the local officials who contributed to the success of phase one of the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project might not have the same level of commitment to the national policy of ecological civilization, but they still managed to get their job done under the Chinese leadership system. Without a doubt, government officials are more exposed to the national policy of ecological civilization than the public with a series of relevant policy documents and ecological-oriented projects similar to the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project. However, unlike residents and professionals who still appeal to relatively plain beliefs with moralistic orientations, officials seem to be scientifically objective, with a highly ecologistic orientation, and somewhat indifferent, with a strong inclination toward strong environmental apathy. It seems that the existing ecological civilization education within the government system has spoken to sense but not to sensibility. This could be an alarming sign if internal resistance begins to gain momentum. In this sense, there are calls for immediate actions of bottom-up planning improvements and ongoing environmental education on important ecological issues to increase moral responsibility and make it possible for people to genuinely embrace the policy of ecological civilization that is currently imposed from the top down.

Conclusions

This study points out that environmental ethics and ecological civilization share the same theoretical roots in Whitehead’s process philosophy and demonstrates the importance of the theoretical development of environmental ethics in urban-applied fields. With its increased diversity and specificity, it can provide detailed explanations of motivation to help raise awareness of ecological civilization and facilitate consensus building. Aligning with the theoretical progress in environmental ethics, the AEA scale adapted in this study is a more fine-grained tool for assessing environmental attitudes, with strong explanatory power and potential value when applied to UGI planning and management.

The implementation and findings of this adapted scale in the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project provide an excellent example. The stakeholders involved have similar environmental attitudes of weak-anthropocentrism with slight inclination differences toward strong-anthropocentrism across subgroups. Importantly, it also unveils the potential hidden conflicts in the internal values of the local officials who align with two different orientations of ecocentric and environmental apathy. In addition, the public is more sensitive to moralistic statements, and the naturalistic experience appeals to them the most. The internal conflicts among officials and the knowledge gap between professionals and residents require ongoing environmental education and policies to raise awareness of important ecological issues instead of simply imposing a policy of ecological civilization from the top down.

With its strong perspective explanation power, this AEA scale could be used to facilitate bottom-up stakeholder participation and a consensus-building process of crafting and communicating urban planning and management policies. Urban and landscape professionals could use this AEA scale early in UGI projects to better understand stakeholders’ environmental value patterns and tailor their proposals and policies. This means that this scale can inform actionable policy implications not only for the future phases of the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project but also universally for projects outside China.

There are several potential lines of further study to expand the knowledge and understanding of environmental ethic theories for use in UGI planning and management. First, building on the quantitative analysis of this study, follow-up qualitative studies such as interviews with the stakeholders of the ZJG Bay Eco-Park could provide more in-depth insights to explain the underlying reasons for their environmental attitudes and sources of internal confusion and conflicts. Second, since the ZJG Bay Eco-Park project is still in progress, it would benefit from a longitudinal study to determine the stakeholders’ environmental attitudes and value changes over time to potentially understand the mutual impacts of implementing UGI projects like this one and to shape environmental attitudes and values toward an ecological civilization. Third, more comparative studies, such as across countries or subpopulations, could consolidate an expanded knowledge in this important field of study. Another potential for further study is inspired by a lesson learned while conducting this case study. This AEA scale is limited to 20 statements for easier practical implementation, which also reduces the number of Kellert’s typologies involved. Further studies might consider making the AEA scale longer to include more Kellert’s typologies to test and optimize the tool.

Data Availability Statement

All data, models, and codes generated or used during the study appear in the published article.

Acknowledgments

This project is funded by the University Research Centre for Urban and Environmental Studies of Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (UES-WJ-21032106) and Jing Lu's Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Grant No. 945139 (European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovative Programme) as part of her dissertation process. The authors thank Fundación Tatiana Pérez de Guzman el Bueno for their financial support, Susana Martín Fernández (Universidad Politécnica de Madrid) for all her help with the statistical analysis of this article, and the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

References

Aronson, M. F., C. A. Lepczyk, K. L. Evans, M. A. Goddard, S. B. Lerman, J. S. MacIvor, C. H. Nilon, and T. Vargo. 2017. “Biodiversity in the city: Key challenges for urban green space management.” Front. Ecol. Environ. 15 (4): 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1480.

Callicott, J. B. 1980. “Animal liberation—A triangular affair.” Environ. Ethics 2 (4): 311–338. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics19802424.

Callicott, J. B. 1992. “Rolston on intrinsic value: A deconstruction.” Environ. Ethics 14 (2): 129–143. https://doi.org/enviroethics199214229.

Cameron, R. W. F., and T. Blanuša. 2016. “Green infrastructure and ecosystem services—Is the devil in the detail?” Ann. Bot. 118 (3): 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcw129.

Chang, Y.-H., Y.-D. Lin, S.-L. Deng, and K.-C. Liu. 2011. “An explore of relationship between attitude of new environmental paradigm and responsible environmental behavior—An example of Chiayi Arboretum.” [In Chinese.] 林业研究季刊 33 (2): 13–27. https://doi.org/10.29898/SHBQ.201106.0002.

Cocks, S., and S. Simpson. 2015. “Anthropocentric and ecocentric: An application of environmental philosophy to outdoor recreation and environmental education.” J. Experiential Educ. 38 (3): 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825915571750.

Delavari-Edalat, F., and M. R. Abdi. 2010. “Human–environment interactions based on Biophilia values in an urban context: Case study.” J. Urban Plann. Dev. 136 (2): 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9488(2010)136:2(162).

Diehm, C. 2012. “Biophilia and biodiversity: Environmental ethics in the work of Stephen R. Kellert.” Environ. Ethics 34 (1): 51–66. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics20123415.

Dunlap, R. E., and R. E. Jones. 2002. “Environmental concern: Conceptual and measurement issues.” In Handbook of environmental sociology, edited by R. E. Dunlap and W. Michelson, 482–524. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Dunlap, R. E., and K. D. Van Liere. 1978. “The ‘New environmental paradigm’.” J. Environ. Educ. 9 (4): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1978.10801875.

EPA. 2022. “Overcoming barriers to green infrastructure.” Green Infrastructure. Government. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://www.epa.gov/green-infrastructure/overcoming-barriers-green-infrastructure.

Goldman, M. J., M. D. Turner, and M. Daly. 2018. “A critical political ecology of human dimensions of climate change: Epistemology, ontology, and ethics.” WIREs Clim. Change 9 (4): e526. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.526.

Hagemann, N., H.-P. Schmidt, R. Kägi, M. Böhler, G. Sigmund, A. Maccagnan, C. S. McArdell, and T. D. Bucheli. 2020. “Wood-based activated biochar to eliminate organic micropollutants from biologically treated wastewater.” Sci. Total Environ. 730: 138417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138417.

Henning, B. G. 2016. “Unearthing the process roots of environment ethics—Whitehead, Leopold, and the land ethic.” Balkan J. Philos. 8 (1): 3–12. https://doi.org/10.5840/bjp2016811.

Hong, D. 2006. “Measurement of environmental concern: Application of the NEP scale in China.” [In Chinese.] Society 26 (5): 71–92. https://doi.org/10.15992/j.cnki.31-1123/c.2006.05.003.

Hong, D., and Y. Fan. 2016. “Measuring public environmental knowledge: The development of an indigenous instrument and its assessment.” J. Remin Univ. China 30 (4): 110–121.

Kaltenborn, B. P., and T. Bjerke. 2002. “Associations between environmental value orientations and landscape preferences.” Landsc. Urban Plan. 59 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(01)00243-2.

Kellert, S. R. 1991. “Japanese perceptions of wildlife.” Conserv. Biol. 5 (3): 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.1991.tb00141.x.

Kellert, S. R. 1996. The value of life: Biological diversity and human society. Washington, DC: Island.

Kopnina, H., and A. Cocis. 2017. “Environmental education: Reflecting on application of environmental attitudes measuring scale in higher education students.” Educ. Sci. 7 (3): 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7030069.

Lalonde, R., and E. L. Jackson. 2002. “The new environmental paradigm scale: Has it outlived its usefulness?” J. Environ. Educ. 33 (4): 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960209599151.

La Trobe, H. L., and T. G. Acott. 2000. “A modified NEP/DSP environmental attitudes scale.” J. Environ. Educ. 32 (1): 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960009598667.

Leopold, A. 1949. A sand county almanac. New York: Oxford University Press.

Luo, Y., and J. Deng. 2008. “The new environmental paradigm and nature-based tourism motivation.” J. Travel Res. 46 (4): 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507308331.

Maloney, M. P., and M. P. Ward. 1973. “Ecology: Let’s hear from the people: An objective scale for the measurement of ecological attitudes and knowledge.” Am. Psychol 28 (7): 583–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034936.

Norton, B. G. 1984. “Environmental ethics and weak anthropocentrism.” Environ. Ethics 6 (2): 131–148. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics19846233.

Norton, B. G. 1995. “Applied philosophy versus practical philosophy: Toward an environmental policy integrated according to scale.” In Environmental philosophy and environmental activism, edited by D. Marietta and L. Embree, 125–148. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Parris, K. M., et al. 2018. “The seven lamps of planning for biodiversity in the city.” Cities 83: 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.06.007.

Pickett, S. T. A., M. L. Cadenasso, J. M. Grove, C. H. Nilon, R. V. Pouyat, W. C. Zipperer, and R. Costanza. 2001. “Urban ecological systems: Linking terrestrial ecological, physical, and socioeconomic components of metropolitan areas.” Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 32 (1): 127–157. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114012.

Roberts, J. 2020. “Political ecology.” In The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Felix Stein. Facsimile of the first edition in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.29164/20polieco.

Røskaft, E., B. Händel, T. Bjerke, and B. P. Kaltenborn. 2007. “Human attitudes towards large carnivores in Norway.” Wildl. Biol. 13 (2): 172–185. https://doi.org/10.2981/0909-6396(2007)13[172:HATLCI]2.0.CO;2.

Seto, K. C., B. Guneralp, and L. R. Hutyra. 2012. “Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109 (40): 16083–16088. https://doi.org/www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1211658109.

Stern, P. C., L. Kalof, T. Dietz, and G. A. Guagnano. 1995. “Values, beliefs, and proenvironmental action: Attitude formation toward emergent attitude objects.” J. Appl. Social Psychol. 25 (18): 1611–1636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb02636.x.

Thompson, S. C. G., and M. A. Barton. 1994. “Ecocentric and anthropocentric attitudes toward the environment.” J. Environ. Psychol. 14: 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80168-9.

Thorne, P. W., et al. 2018. “Towards a global land surface climate fiducial reference measurements network.” Int. J. Climatol. 38 (6): 2760–2774. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5458.

United Nations. 2021. “Zhangjiagang Bay: Practice of Ecological Restoration in China.” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. NGO. Accessed April 22, 2022. https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/zhangjiagang-bay-practice-ecological-restoration-china.

Wang, Z., M. Fan, and J. Cobb Jr. 2020. “Chinese environmental ethics and Whitehead’s philosophy.” Environ. Ethics 42 (1): 73–91. https://doi.org/10.5840/enviroethics20204217.

Weigel, R., and J. Weigel. 1978. “Environmental concern: The development of a measure.” Environ. Behav. 10 (1): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916578101001.

Whitehead, A. N., D. R. Griffin, and D. W. Sherburne. 1978. “Process and reality: An essay in cosmology.” In Gifford Lectures, edited by D. R. Griffin and D. W. Sherburne, 1927–1928. New York: Free Press.

Wilson, E. O. 1984. Biophilia. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Wu, J., F. Zi, X. Liu, G. Wang, Z. Yang, M. Li, L. Ye, J. Jiang, and Q. Li. 2012. “Measurement of new ecological paradigm: Revision and application of NEP scale in China.” [In Chinese.] J. Beijing For. Univ. 11 (4): 8–13. https://doi.org/10.13931/j.cnki.bjfuss.2012.04.022.

Wu, L., and Y. Zhu. 2017. “Revision of new ecological paradigm (NEP) scale in urban student groups in China and its reliability and validity test.” [In Chinese.] J. Nanjing Ind. Univ. 16 (2): 53–61. https://doi.org/1671-7287(2017)02-0053-09.

Wu, W., and G. Wallace. 2014. “A postmodern China in the making.” Process Stud. 43 (1): 68–74.

Yu, X. 2014. “Is environment ‘a city thing’ in China? Rural–urban differences in environmental attitudes.” J. Environ. Psychol. 38: 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.12.009.

Zuniga-Teran, A. A., C. Staddon, L. de Vito, A. K. Gerlak, S. Ward, Y. Schoeman, A. Hart, and G. Booth. 2020. “Challenges of mainstreaming green infrastructure in built environment professions.” J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 63 (4): 710–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1605890.

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Copyright

This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

History

Received: Jul 24, 2022

Accepted: May 8, 2023

Published online: Sep 19, 2023

Published in print: Dec 1, 2023

Discussion open until: Feb 19, 2024

ASCE Technical Topics:

- Bays

- Business management

- Case studies

- Coastal engineering

- Coasts, oceans, ports, and waterways engineering

- Construction engineering

- Construction management

- Ecological restoration

- Ecosystems

- Engineering fundamentals

- Engineering profession

- Environmental engineering

- Ethics

- Infrastructure

- Methodology (by type)

- Practice and Profession

- Professional practice

- Project management

- Research methods (by type)

- Sustainable development

- Urban and regional development

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Download citation

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.