Effect of Ruling Decision on the Outcome of Construction Litigation Cases

Publication: Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction

Volume 16, Issue 1

Abstract

Parties involved in architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) have an interest in understanding litigation trends. The AEC community is eager to find ways to prevent or mitigate litigation. There are multiple ways to resolve such claims, with litigation being the longest and costliest route. The ruling decision factor (RDF) is the key element in a given case that a court takes into consideration in reaching the outcome/judgement. In this research exercise, RDF was represented by evidence, a specific law article, preceding court opinion, or contract. Sixty-two construction and engineering cases from Arizona, California, and New Mexico, dating from 2008 to 2021 in the Court of Appeals were evaluated. These cases were analyzed for interactions of the RDF with different, case-specific variables to capture trends and provide an understanding of what drove the case. For example, if the defendant type was a government agency, or the cause of action (a legal term referring to the main reason behind litigation initiation) was an environmental concern, the RDF was evidence. If the cause of action was a warranty issue, the RDF was a contract.

Introduction

With the significant level of competition in the AEC industry, private and public companies have to lower their risk-mitigating markups to be more competitive (Awwad and Ioannou 2012). Understanding the litigation trends can guide the AEC industry to achieve a better-informed decision on whether or not to pursue litigation in a dispute as well as choose between a contract with a particular entity type or not.

Norton Rose Fulbright (AACE 2012), quantifies the trends in litigation in a wide range of businesses from financial institutions, to private technology companies, including construction companies. There was no evaluation or a specific study to understand what affected these trends. Further investigation was needed to better understand what was needed to isolate these trends based on different qualitative categories such as:

•

Defendant and plaintiff types (entity type of the defendant and plaintiff),

•

Cause of action (a legal term referring to the main reason behind litigation initiation),

•

Legal decision factor (the main factor the court took into consideration in reaching the outcome),

•

Legal fees responsibility (Firm or Court fees to be paid by the responsible party),

•

Judge’s gender,

•

Total years of experience in the legal field (years of legal practice, including but not limited to serving as a judge), and

•

Awarded party (plaintiff versus the defendant).

A data set was built by identifying and analyzing construction and engineering-related legal cases from various appeals courts throughout the United States. In this research, cases were collected from the Appeals Courts of Arizona, New Mexico, and California.

Literature Review

Pulket and Arditi examined multiple case outcome predictions modules and stated that the purpose of predicting construction litigation is to encourage settlements outside of court systems (Arditi and Pulket 2005). One model was predicting construction litigation outcomes using boosted decision trees (BDT). That model was built using 132 Illinois Circuit Court cases (In the state of Illinois Circuit Court is equivalent to Superior Court in the State of Arizona) filed between 1987 and 2000. BDT model yielded in 90% prediction rate (Arditi and Pulket 2005).

Another study by Pulket and Arditi used a universal prediction model (UPM) for construction litigation. The study was conducted by using 151 Illinois Circuit Court cases filed from the period 1987 to 2005. The UPM consisted of data consolidation, attribute selection, hybrid classification, and performance assessment. A program was written to automate the entire process in the Waikato environment for data analysis. UPM was proven to be versatile and scalable. The findings resulted in a higher prediction rate than those obtained in previous studies. The system proved to be quite robust and fast (Arditi and Pulket 2009).

Pulket and Arditi went on to examine outcome predictions using an integrated artificial intelligence model. An integrated prediction model (IPM) was used to predict the outcome of construction litigation. With aim, it would generate a higher prediction rate than the rates obtained by using artificial neural networks ANN, case-based reasoning CBR, and boosted decision trees (BDTs) in earlier studies. These studies were conducted by using the same 132 Illinois Circuit Court cases with slight variations in the case of the BDT and IPM studies filed between 1992 and 2000. A prediction rate of 91.15% was obtained, higher than the 66.67% in the ANN study, 83.33% in the CBR study, and 89.59% in the BDT study. IPM involves four processes, namely, data consolidation, attribute selection, prediction using hybrid classifiers, and assessment. The performance of IPM is comparable to the performance of ANN, CBR, and BDT (Arditi and Pulket 2009).

In claim practice, it’s known that the legal team examines the case history, the history of related cases, and the contract before identifying entitlement and responsibilities of their clients. (Niu and Issa 2014). Mahfouz and Kandil (2009, 2011) extracted and quantified impact factors from litigation cases by using multiple methods. Relationships between factors and cases were developed using machine learning methods and a multi-agent system was made to produce legal arguments. This system linked the impact factor and providing a solution to construction disputes using a logic algorithm to simulate legal discourse (Mahfouz and Kandil 2011). Niu and Issa examined the effect of natural language processing (NLP) methodology for semantically interpreting impact factors for construction claim cases. This research proved that NLP techniques provided an automated functionality to the conventional approach of claim outcome prediction (Niu and Issa 2014).

Research Importance

Parties involved in architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) have an interest in understanding litigation trends (Griego and Leite 2016). The AEC industry is eager to find ways to prevent litigation; and to plan for it. For example, the Construction Industry Institute (CII) commissioned a research team to understand how starting a project prematurely could lead to claims disputes (Griego and Leite 2016). The research targeted the parameters that lead to a premature project start, and the kinds of litigation or claims that resulted, and how to avoid them.

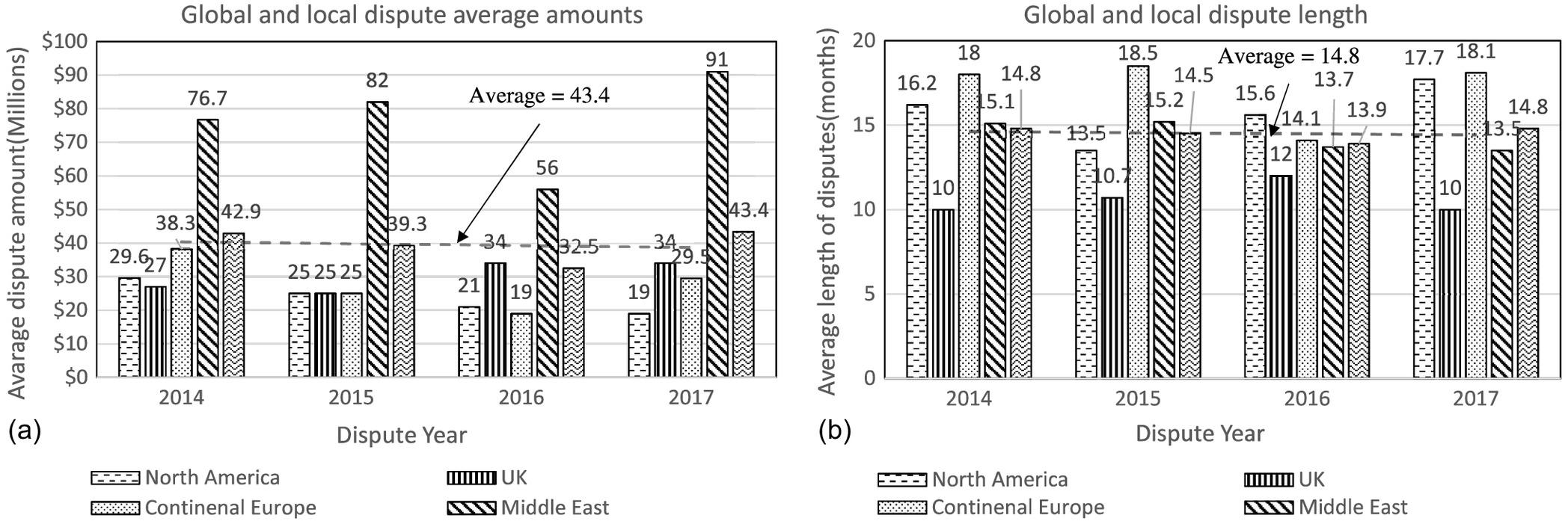

The Global Construction Dispute Report of Arcadis (Cooper et al. 2018) showed;

•

The global average value of a dispute was USD 43.4 million.

•

The global average length of a dispute was 14.8 months.

•

The North American average value of a dispute was USD 19 million.

•

The North American average length of a dispute was 17.7 months.

As shown in Figs. 1(a and b) and the preceding points, the money and time spent on construction litigation are important both globally and locally. Based on data published by the Global Construction Dispute Report of Arcadis (Cooper et al. 2018), if this litigation trend analysis research benefited one of the North American companies in mitigating a potential claim or lawsuit, then the saving will be estimated to be USD 19 million and 17.7 months in money and time spent. Arcadis is a global company delivering sustainable design, engineering, and consultancy solutions for natural and built assets. They publish annual global construction dispute reports based on in-house data; therefore, the average amounts and duration may be subjective and should be used as a point of reference only.

Gad and Shane (2012) researched the selection of construction and engineering claims resolution method through a panel of 11 international DRM experts. Even with the cultural differences that could affect international contracts dispute resolution methods, experts agreed that the most recommended DRM is arbitration.

Table 1 shows that the longest and most expensive dispute resolution method is litigation.

| Point of comparison | DRMs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litigation | Arbitration | Mediation | Adjudication | DAB | Expert determination | |

| Parties involved in the decision | Judges and courts | Arbitrators | Mediators and parties | Adjudicators | Panel of experts | An expert |

| Control level of parties | None | Minor | Full | Average | Average | Minor |

| Decision enforceability | Final and binding | Final and binding | Non-binding | Binding, if stated in court | Non-binding | Final and binding |

| Privacy | Public | Confidential | Confidential | Confidential | Confidential | Confidential |

| Relative duration | Very long | Long | Short | Short-set | Short | Short |

| Relative cost | Very expensive | Expensive | Less expensive | Average | Average | Not expert |

| Notes | Technical knowledge compromised | Technical knowledge not compromised | Solution may not follow contract | Decision can be appealed | DAB knowledgeable of project | Preferred in complex technical issues |

Source: Adapted from Gad (2012).

This study of litigation trends will give insight to decision-makers (lawyers, owners, contractors, and Engineers) to advise as to whether to go the litigation route or chose a dispute resolution method. This study was a statistical qualitative analysis using mosaic plots, as opposed to a quantitative analysis, to observe trends that could potentially be used to assist attorneys and parties to make informed decisions regarding bringing litigation to trial. This study is unique in shedding light on the effect of case variables that are easily identified, on the most probable RDF to be chosen by the court. Understanding the correlation between input and output case variables can drive the decision regarding whether to go the litigation route or chose a different route.

Research Methodology

It was understood that different case types might be governed by different laws and regulations. The purpose of this study was to shed light on the AEC cases regardless of the governing laws. The scope of this research was to study the trends in litigation in the AEC industry and trying not go too deep into the law or the legal system. Cases from three appeal court systems were examined. Cases were sorted by case year and the state where the cases were opened and appealed. The legal case must be appealed in the same judicial system it was started (Supreme Court of the United States Home, n.d.).

Qualitative analysis software (MAXQDA) was used to analyze the selected cases. Cases were taken from Arizona, New Mexico and California ranging from 2008 to 2022. The following keywords were searched in Nexus:

•

Construction.

•

Engineering.

•

Construction injury.

•

Construction contract.

•

Construction litigation.

•

Construction defect.

•

Construction error.

•

Structural engineer.

•

Structural defect.

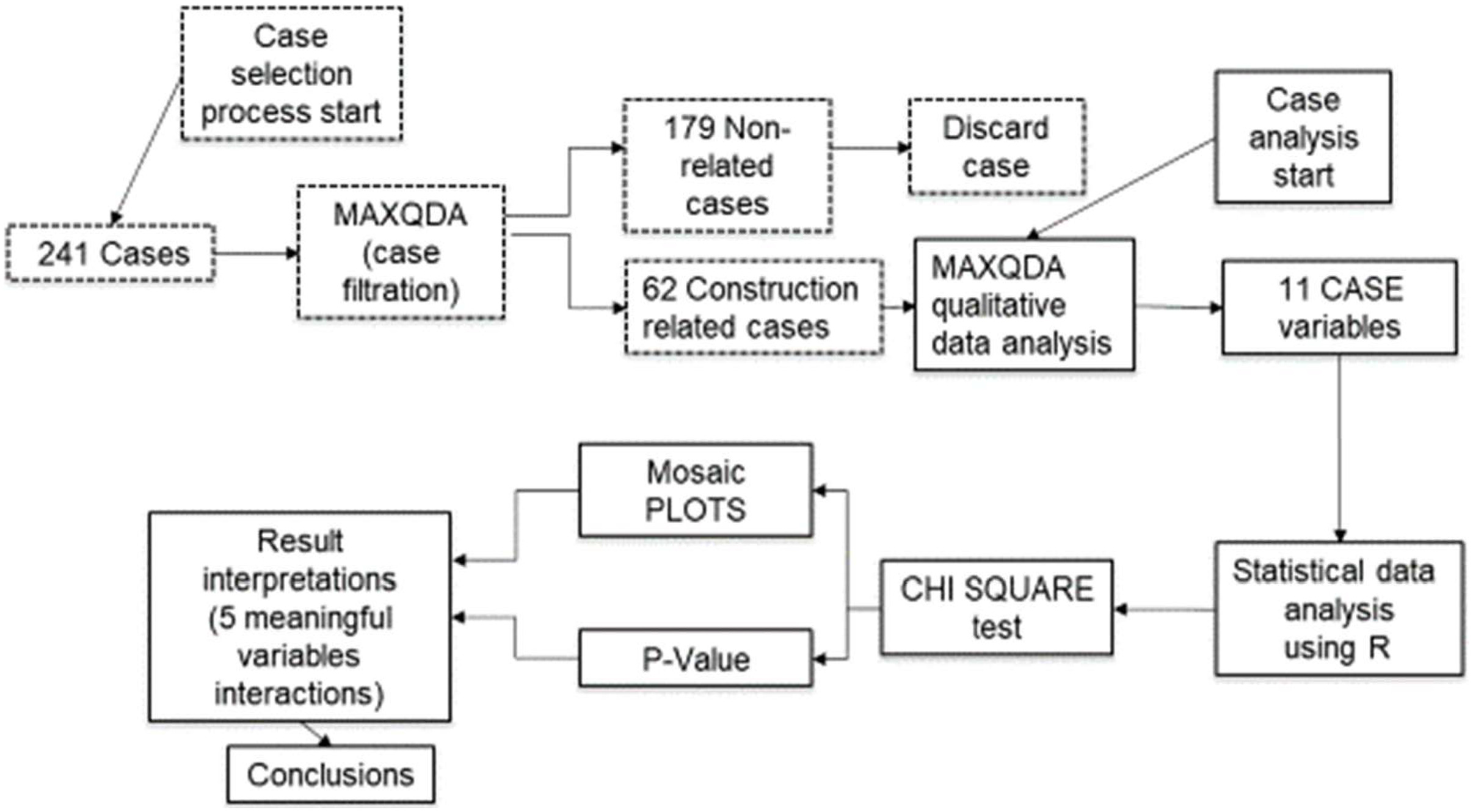

After the relevant cases were identified, they were screened again manually to ensure the remaining cases were of structural or construction-related nature. Fig. 2 illustrates the selection process.

Arditi and Pattanakitchamroon (2008) and Kululanga et al. (2001) based their work in claim prediction on the assumption that the existence of the impact factor should be manually interpreted and determined. Then the user needed to read the case and determine if that text contained a case impact factor.

MXQDA was used as the qualitative data analysis software. It has been previously used for the analysis of qualitative data (Pastrana et al. 2021; Saeidi et al. 2019). Case variables were derived from the documentation. There were seven input variables:

1.

Cause of action,

2.

Case state,

3.

Case year,

4.

Defendant type,

5.

Plaintiff type,

6.

Judge gender, and

7.

Legal practice range.

There were four output variables:

1.

Ruling decision factor,

2.

Case result,

3.

Legal fees responsibility, and

4.

Structural issue.

After analyzing the cases, the resulting data was used as the source for the statistical data analysis software, R.

In all the cases examined, the appeal courts have three judges that form a judge’s panel in reviewing cases. The judge who gave the opinion is the judge whose details were used for the corresponding case variables (judge legal practice and judge gender). The judge’s legal practice was taken into consideration via searching for the judge’s name and recording how many years of legal experience, both as a practicing attorney and as a judge, the judge possesses. This is public information published by the court of appeal they served in.

In statistical language, each case represented an incident that was a series of variables that have been captured using MAXQDA and was analyzed using R. The statistical data analysis software R was used to perform the chi-square test, contingency tables, mosaic plots, and calculated P-Values. Result interpretations were based on the mosaic plots and P-values graphs.

It is widely known in the research community that the traditioned P-value threshold used should be . This P-value can be traced to Fisher (1925), where Fisher published:

The value for which , or 1 in 20, is 1.96 or nearly 2; it is convenient to take this point as a limit in judging whether a deviation ought to be considered significant or not. Deviations exceeding twice the standard deviation are thus formally regarded as significant. Using this criterion, we should be led to follow a false indication only once in 22 trials, even if the statistics were the only guide available. Small effects will still escape notice if the data are insufficiently numerous to bring them out, but no lowering of the standard of significance would meet this difficulty. (Fisher 1925, p. 14)

There is no formal requirement to use a P-value of 0.05 in the research and scientific community. The selection of the P-value is left to the researcher to set a comfortable level of confidence (Di Leo and Sardanelli 2020).

In 2016, the American Statistical Association (ASA) published an article shedding some light on P-value meaning and other important warnings and guidelines (Greenland et al. 2016). In that article, the ASA stated that the P-value did not measure the probability that the studied hypothesis was true; nor scientific conclusions and business policies could be based only on a p-value passing a specific threshold; however,

Researchers should look at other affecting factors, derive scientific inferences, including the methodology, collection of the data sets and the way to analyze them, the quality of the measurements, the external evidence for the phenomenon under study, and the validity of assumptions that underlie the data analysis. (Wasserstein and Lazar 2016, p. 133)

Understanding Mosaic Plots

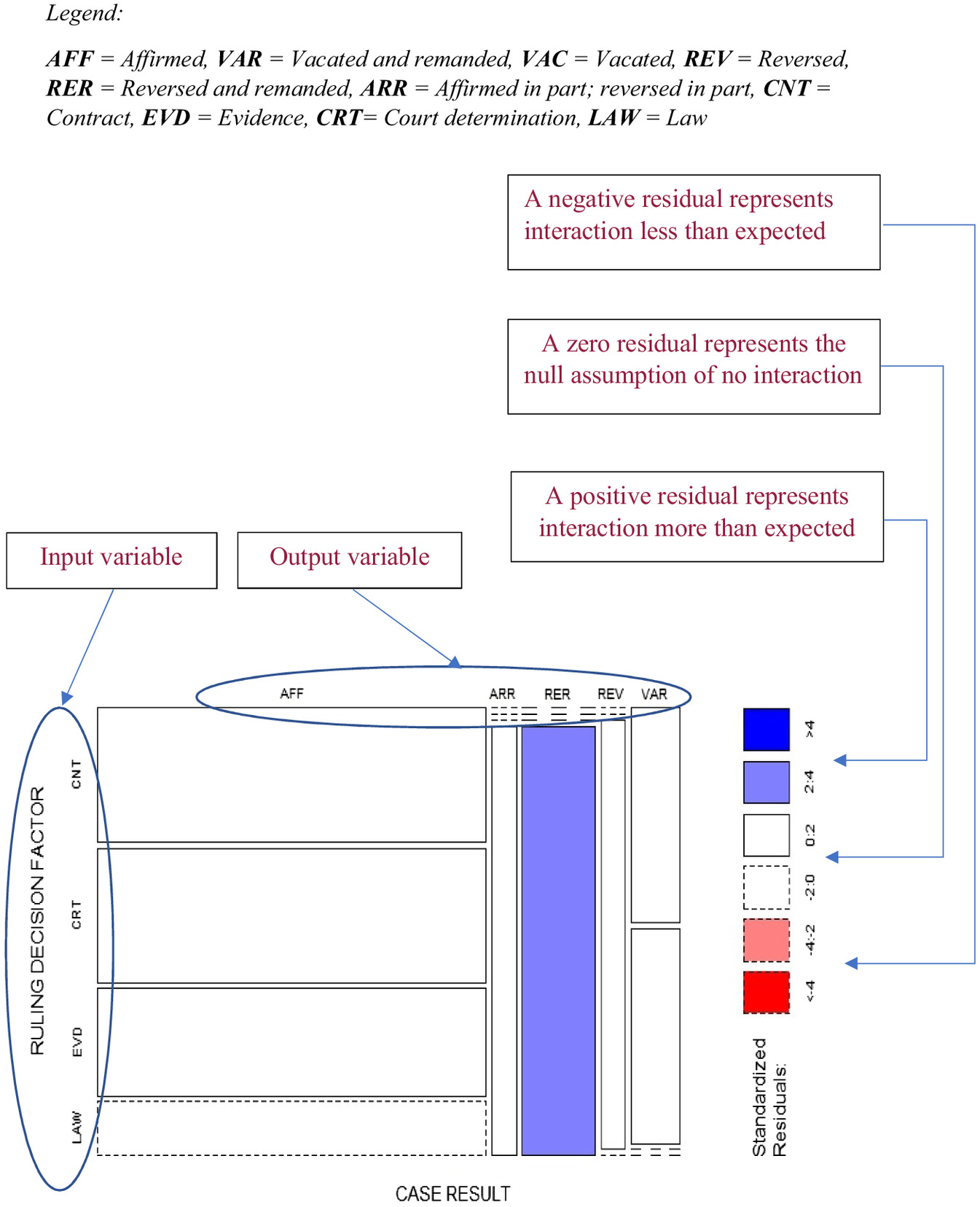

Mosaic plots represent visual interactions between two variables. Showing the deviation from the expected values of independence in a form of standardized residuals via color/shade. The expected values are a representation of independent variable values (i.e., no relationship between the variables) (Cran, n.d.). Mosaic plots have been used in research to study the interaction of two categorical variables. For example, Sanaz used mosaic plots to show the frequency of route choices under each experimental scenario (Saeidi et al. 2019).

Fig. 3 shows an example of a mosaic plot. The left vertical axis shows the input variable: in this study, it was the ruling decision factor (RDF). The horizontal top axis represents the output variables leading to the case result (CR). The shading of the tiles represents the standardized residuals. A positive residual means that there are more observations than the expected null hypotheses (positive correlation between two variables) and vice versa for the negative residuals. The standardized residual values between 2 and 4 means there are more observations in that cell (containing correlation between two variables) than the expected null hypotheses. Units are in standard deviations so a value of 2 represents a significant departure from the independence (no relationship between variables) (Zavarella 2018).

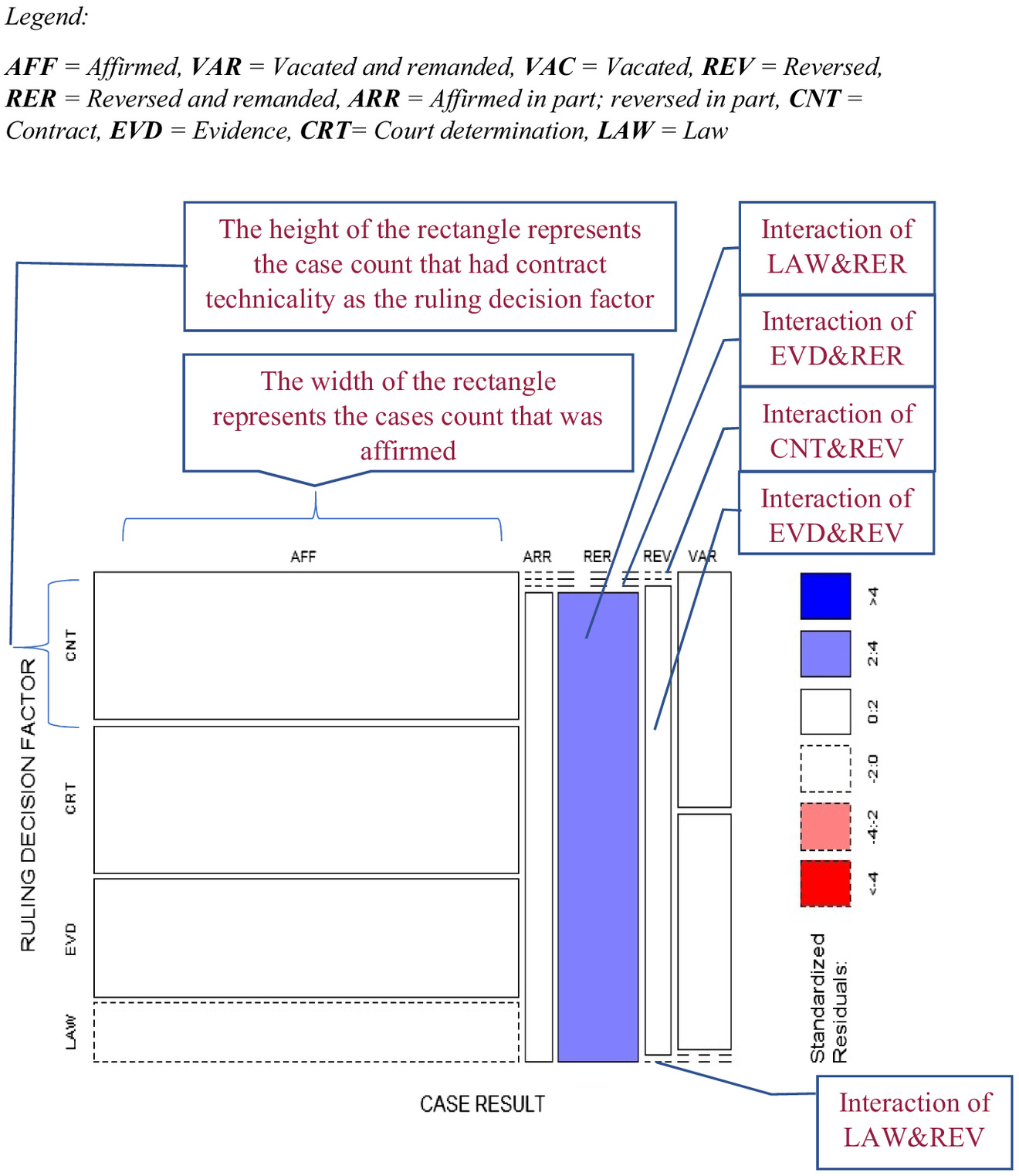

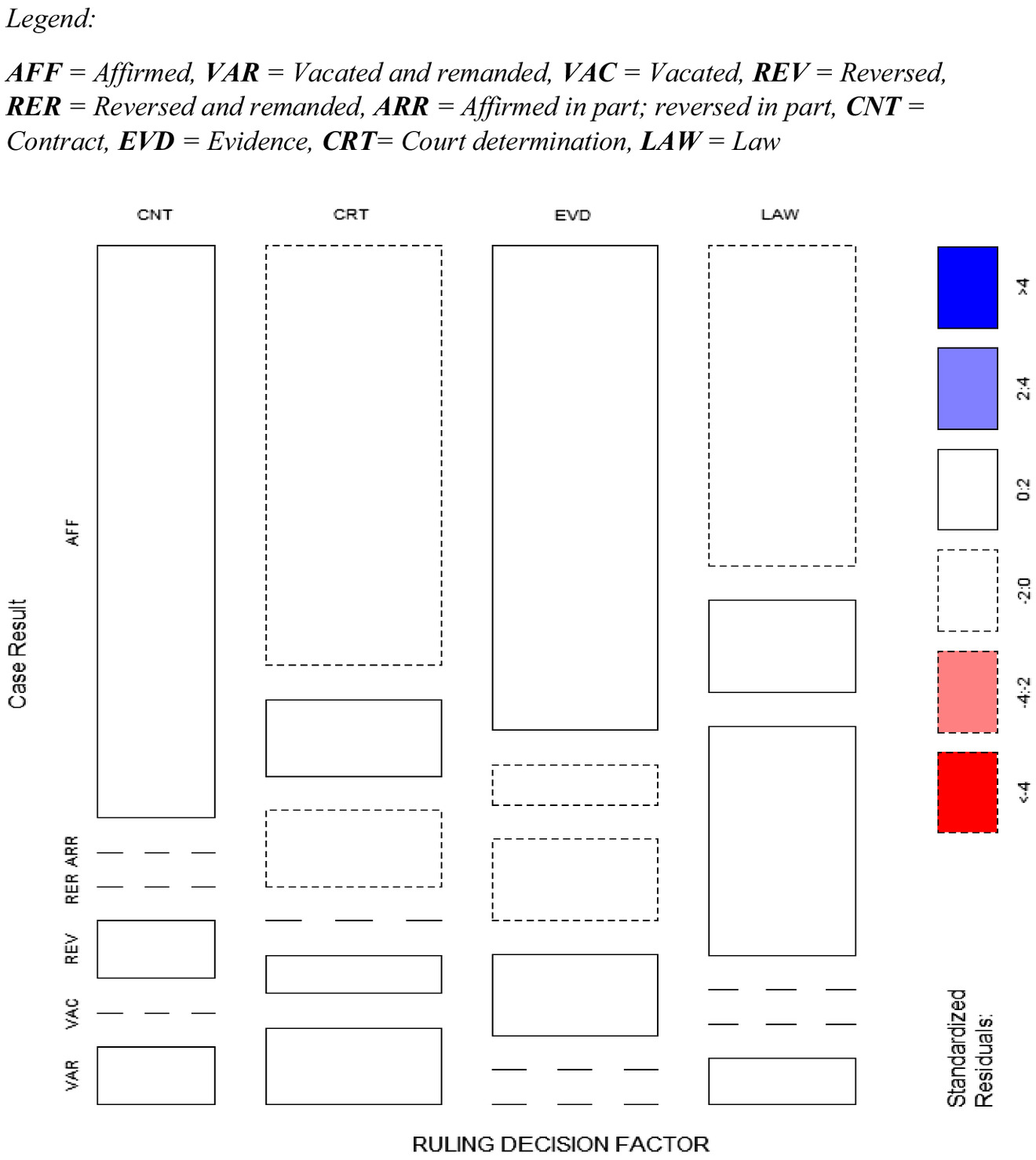

Fig. 4 shows the same mosaic plot as Fig. 3, with an explanation of the width and height of each tile. The height of the tiles represents the portion of the observation count for each input variable. The width of the tiles represents the portion of the observation count for each of the output variables. Notice the tile size of the LAW and RER versus the single dashed line tile of LAW and REV interaction.

In this study, the standardized residual values above or below were taken as significant interactions. The standardized residual units are in standard deviations, so a value of 2 represents a significant departure from the independence. Meaning, when the value of residuals is above or below , the two variables are correlating (Zavarella 2018).

RDF refers to the main factor the court took into consideration in reaching the outcome. Additional variables were not specifically included in this study, as they were either included within existing variables or were excluded for lack of data availability:

1.

Damages sought were included in defective construction (DEC) which is an input variable under cause of action.

2.

Delay was included in contract breach, which is under cause of action (COA).

3.

Procurement type can affect input variables in the future; however, it was not considered as that information was not published in the cases used for this study.

4.

Claim type: civil, structural, architectural, HVAC, etc. These input variables were not always available in the case studied, and most of the cases were directed to the contractor. The output variable of a structural issue (SI) was used to identify if a case had a structural issue that could have an effect on the ruling decision factor (RDF).

In this research, the factor could be:

•

LAW (Law): Application of specific law article.

•

EVD (Evidence): Proven tangible evidence considered by the court.

•

CRT (Court): Court determination of claim: meaning how the court interpreted the claims between the defendant and the plaintiff (court and Judge authority).

•

CNT (Contract): This means that the court depended on the contract between the two parties in reaching the final ruling in that case.

Barry (2023) explored how factors affect the decision-making of courts. Those factors were the psychological effects of group dynamics, numerical reasoning, biases, court processes, influences from political and other institutions, and technological advancement. This study focused on factors directly related to the case court interpretation and the application of law as stated in the ruling decision. The four ruling decision factors used in this study (law, evidence, court determination of claim, and contract) were derived from the cases reviewed depending on the final decision of the court as stated. For example, when the court decision discusses an evidentiary basis, the ruling decision factor was considered evidence (EVD), but where the court decision refers to a clause in the contract the ruling decision factor was considered contract (CNT).

Chi-Square Test Theory Summary

The chi-square distribution can be used to test whether observed data differ significantly from theoretical expectations. In other words, the chi-square test of independence is used to determine if there is a significant relationship between two nominal (categorical) variables. The frequency of each category for one nominal variable is compared across the categories of the second nominal variable. The data can be displayed in a contingency table where each row represents a category for one variable and each column represents a category for the other variable (Cran, n.d.).

A chi-square (X2) statistic is used to investigate whether distributions of categorical variables differ from one another

Or

Under the assumption of independence, these values roughly correspond to two-tailed probabilities

and that is a given value of [] exceeds 2 or 4.

In other words, residuals depend on P-value; if you have one you can closely estimate the other.

Results Discussion

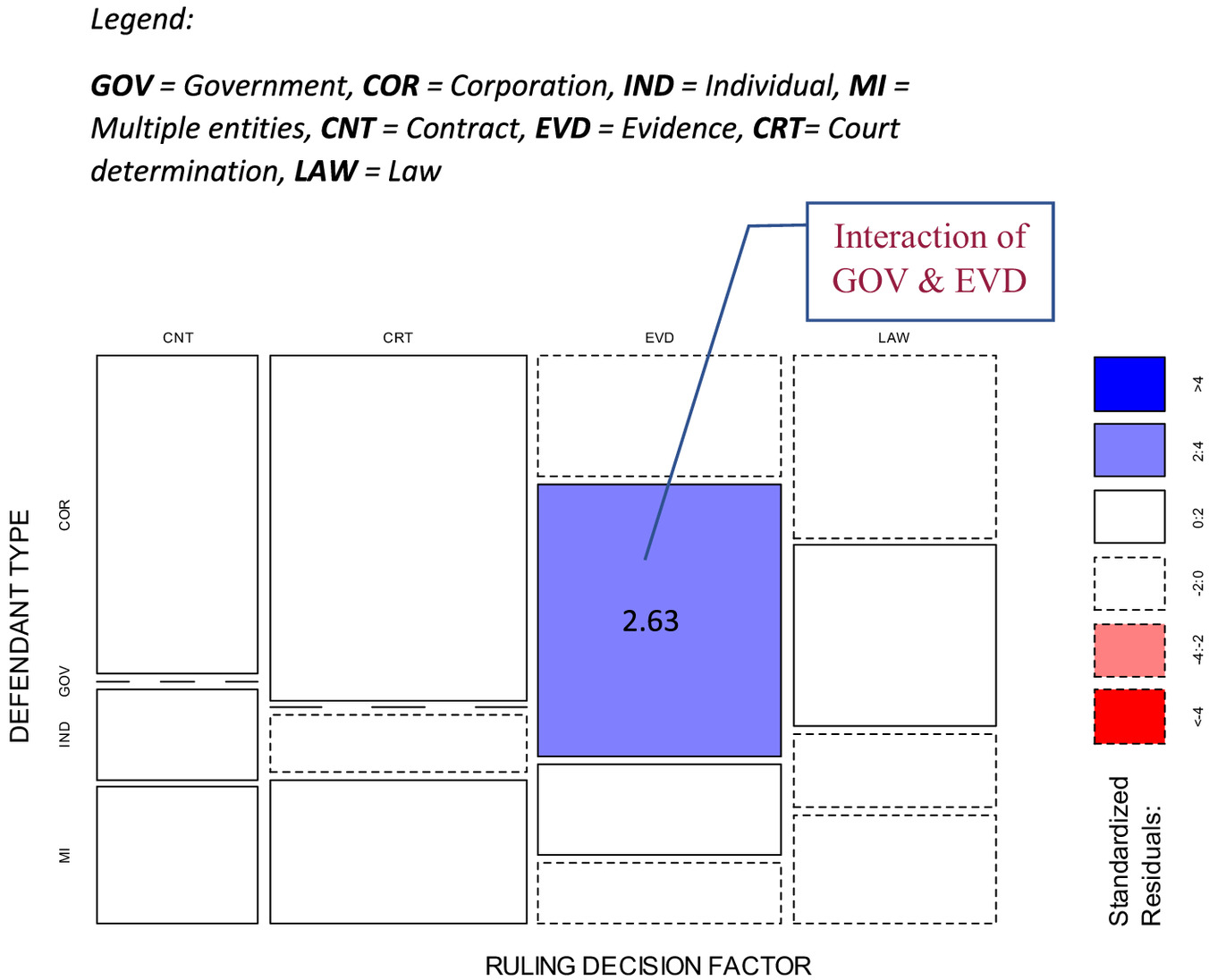

Fig. 5 is a mosaic plot that identifies the interaction between the defendant type (DT) and the ruling decision factor. From the standardized residuals, when the defendant type was government (GOV); the ruling decision factor was of an evidentiary (EVD) nature, which is shown by the presence of a standardized residual value of 2.63. This was an indication of more observations in that cell than the expected null hypotheses. Units were in standard deviations, so a value of 2.63 represented a significant departure from the variables’ independence assumption (Zavarella 2018).

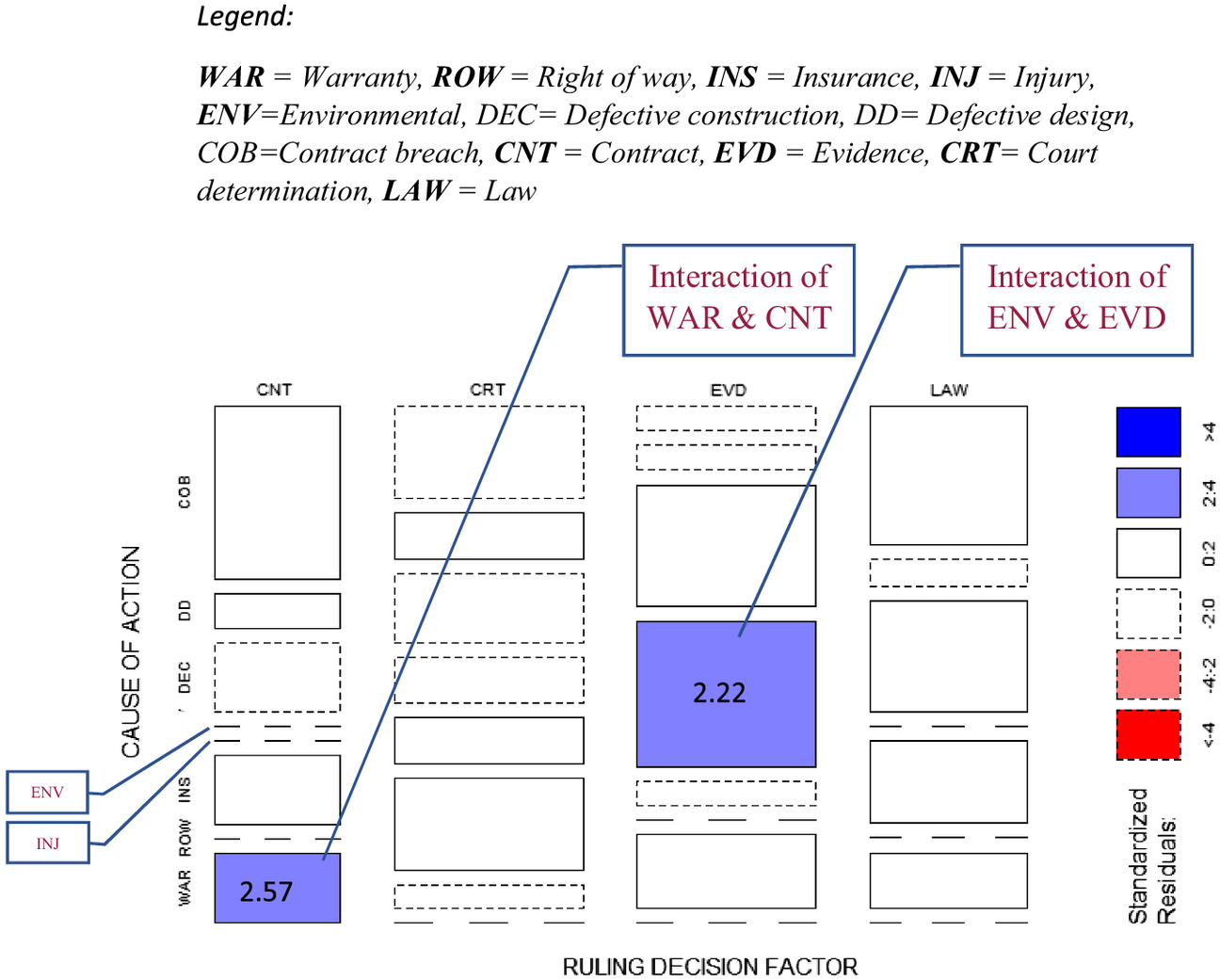

The analysis shown in Fig. 6 emphasized that when the cause of action was a warranty issue (WAR) the ruling decision factor was contract (CNT) with a residual value of 2.57. This meant the court based the judgment on the warranty contract between the defendant and the plaintiff (PLT) or owner and the warranty company. Another observation of this analysis was when the cause of action was an environmental concern (ENV) the court based the decision on evidence more than other factors, with shown interaction of ENV and EVD with a residual value of 2.22.

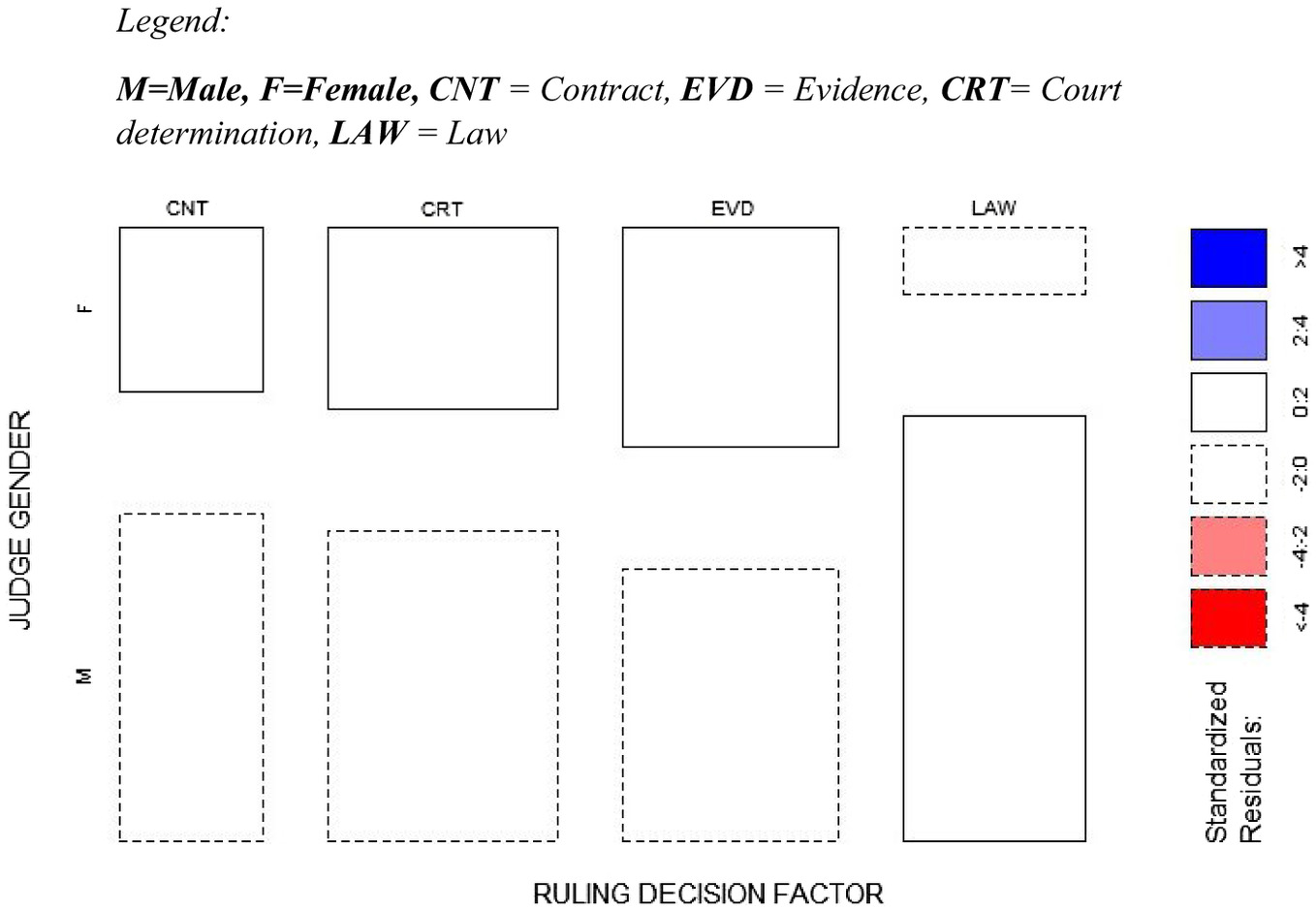

The analysis represented in Fig. 7 showed that the judge’s gender did not affect the ruling decision factor of a specific case. Male or female judges relied on similar decision factors. This type of mosaic plot showed a lack of correlation.

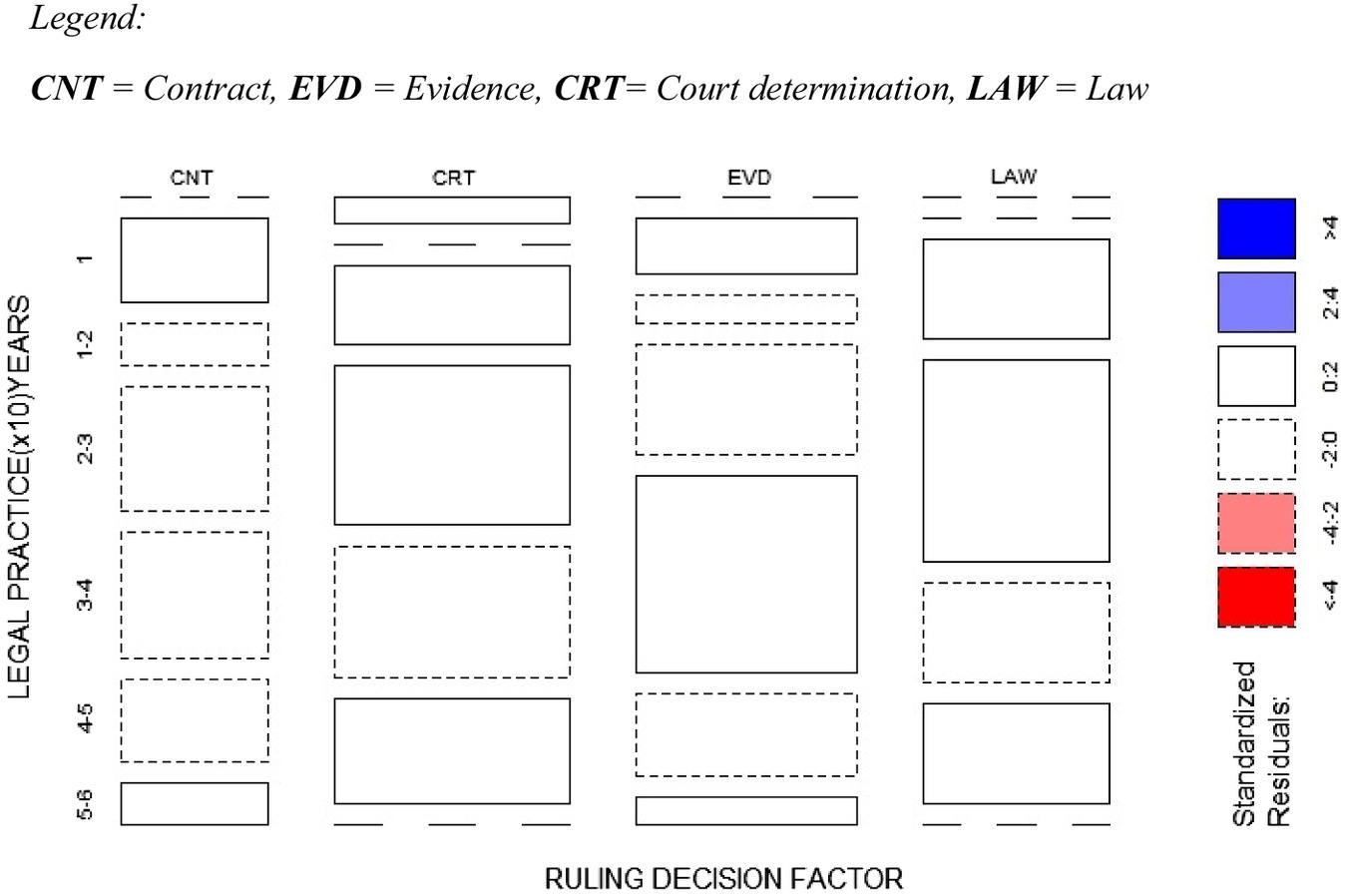

Fig. 8 showed there was no significant interaction between the judge’s total years of legal practice, both as a practicing attorney and as a judge, and the specific ruling decision factor (RDF). The amount of legal practice a judge has did not affect the direction of the judge’s opinions of the case. Given that every case was unique, and the true drivers was the characteristics and parameters of the case rather than the Judge’s total years of legal experience.

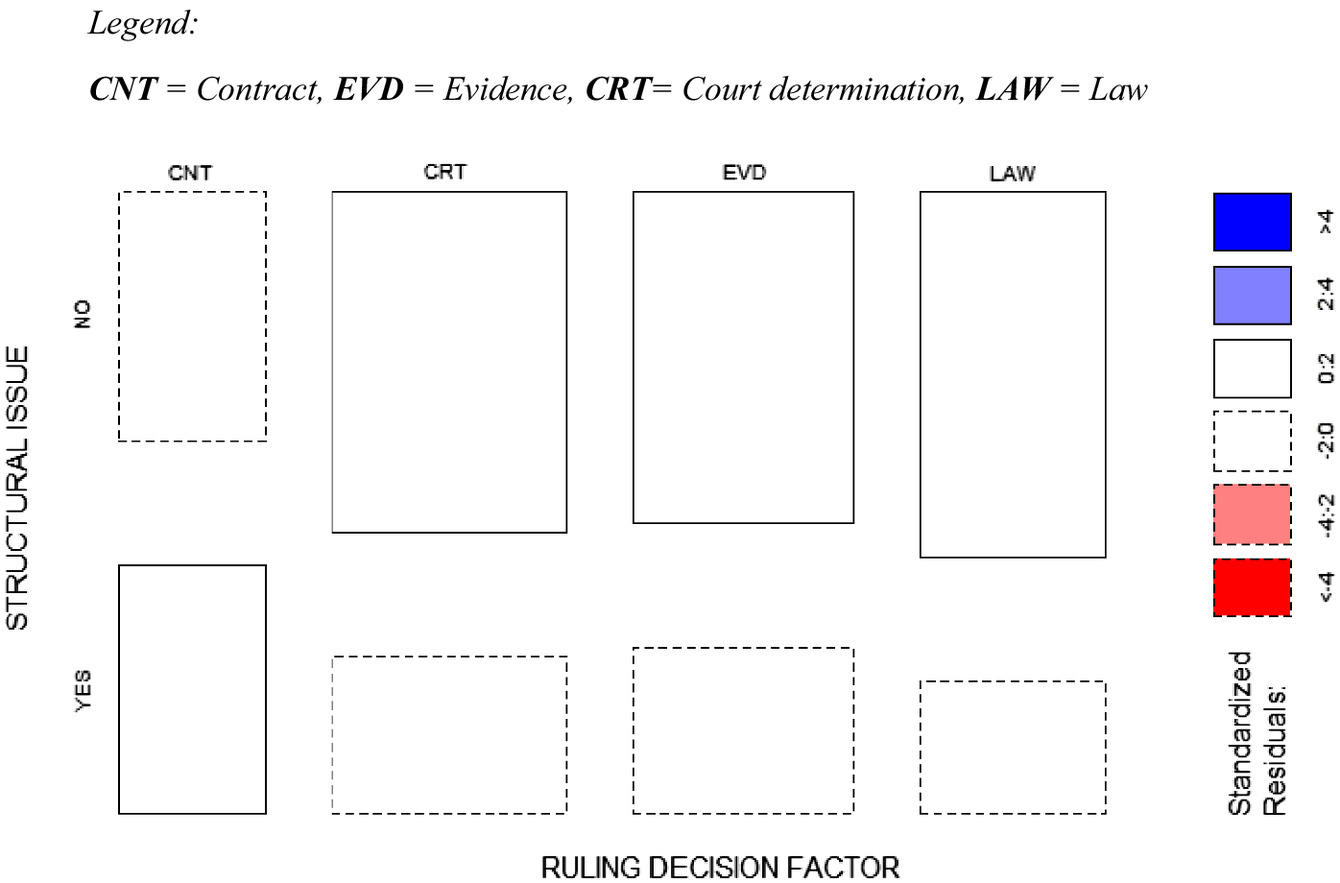

An unexpected observation is shown in Fig. 9, the case structural issue had no bearing on the ruling decision factor and thus no effect on the case result. For example, if the case had a structural issue, it did not push the court to rely on evidence (EVD), nor contract (CNT) as one would expect.

There was no significant interaction between the ruling decision factor (RDF) and the case result (CR), plaintiff type (PT) nor case year (CY). The case result did not depend on the ruling decision factor chosen by the court, shown in Fig. 10.

There was no significant interaction between the ruling decision factor (RDF) and the case state (CST). The case result did not depend on the ruling decision factor chosen by the court. There was no significant interaction between the ruling decision factor (RDF) and who won the case or ruled in favor (RIF) of. The winning party did not depend on or correlate with the ruling decision factor chosen by the court. There was an absence of significant interaction between the ruling decision factor (RDF) and the party responsible of the legal fees (LFR). The ruling decision factor chosen by the court did not affect whether or not the party is responsible for the legal fees. While not all interactions can be considered significant, it is beneficial to show the full residuals list between the RDF and other variables. These are shown in Table 2.

| Variable | Year | RDF (ruling decision factor) residuals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNT | CRT | EVD | LAW | ||

| CY (case year) | 2008 | 0.451 | 0.56 | 0.56 | |

| 2009 | 0.95 | 0.45 | |||

| 2010 | 0.77 | 1.05 | |||

| 2011 | 0.19 | 1.49 | |||

| 2012 | 0.25 | 0.77 | |||

| 2013 | 1.83 | ||||

| 2014 | 0.046 | 0.64 | 0.15 | ||

| 2015 | 1.39 | ||||

| 2016 | 0.195 | 1.49 | |||

| 2017 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 1.48 | ||

| 2018 | 0.55 | 1.29 | |||

| 2019 | 0.985 | 0.6 | |||

| 2020 | 1.54 | ||||

| DT (defendant type) | MI (multiple entities) | 1.62 | |||

| IND (individual) | 0.36 | 0.1 | |||

| GOV (government) | 0.86 | 0.03 | |||

| COR (corporation) | 1.12 | ||||

| PT (plaintiff type) | MI (multiple entities) | 0.305 | 0.63 | ||

| IND (individual) | 0.362 | 0.04 | |||

| GOV (government) | 2.634 | 0.87 | |||

| COR (corporation) | 0.77 | ||||

| COA (cause of action) | WAR (warranty) | 2.59 | |||

| ROW (right of way) | 1.05 | 0.45 | |||

| INS (insurance) | 0.77 | 1.71 | |||

| INJ (injury) | 0.19 | 1.28 | |||

| ENV (environmental) | 2.57 | ||||

| DEC (defective construction) | 0.59 | 0.33 | |||

| DD (defective design) | 0.03 | 0.45 | |||

| COB (contract breach) | 1.23 | 0.719 | |||

| JG (judge gender) | M (male) | 0.89 | |||

| F (female) | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.64 | ||

| LPR (legal practice range) | 1 | 1.86 | 0.19 | ||

| 1–2 | 0.44 | 0.76 | |||

| 2–3 | 0.2 | 0.65 | |||

| 3–4 | 1.08 | ||||

| 4–5 | 0.27 | 0.05 | |||

| 5–6 | 0.98 | 0.6 | |||

| SI (structural issue) | Yes | 0.844 | 0.01 | ||

| No | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.425 | ||

| CR (case result) | VAR (vacated and remanded) | 0.256 | 0.77 | 0.03 | |

| VAC (vacated) | 1.31 | ||||

| REV (reversed) | 0.55 | 1.29 | |||

| RER (reversed and remanded) | 1.912 | ||||

| ARR (affirmed in part; reversed in part; remanded) | 0.45 | 0.718 | |||

| AFF (affirmed) | 0.811 | 0.31 | |||

| CS (case state) | AZ | 0.249 | 1.23 | ||

| CA | 0.66 | 1.2 | |||

| NM | 0.55 | 1.495 | |||

| LFR (legal fees responsibility) | PLT (plaintiff) | 1.08 | 0.22 | ||

| DEF (defendant) | 0.2 | 0.18 | |||

| BP (both parties) | 0.12 | 0.6 | |||

Chi-Square Test Results and Explanation

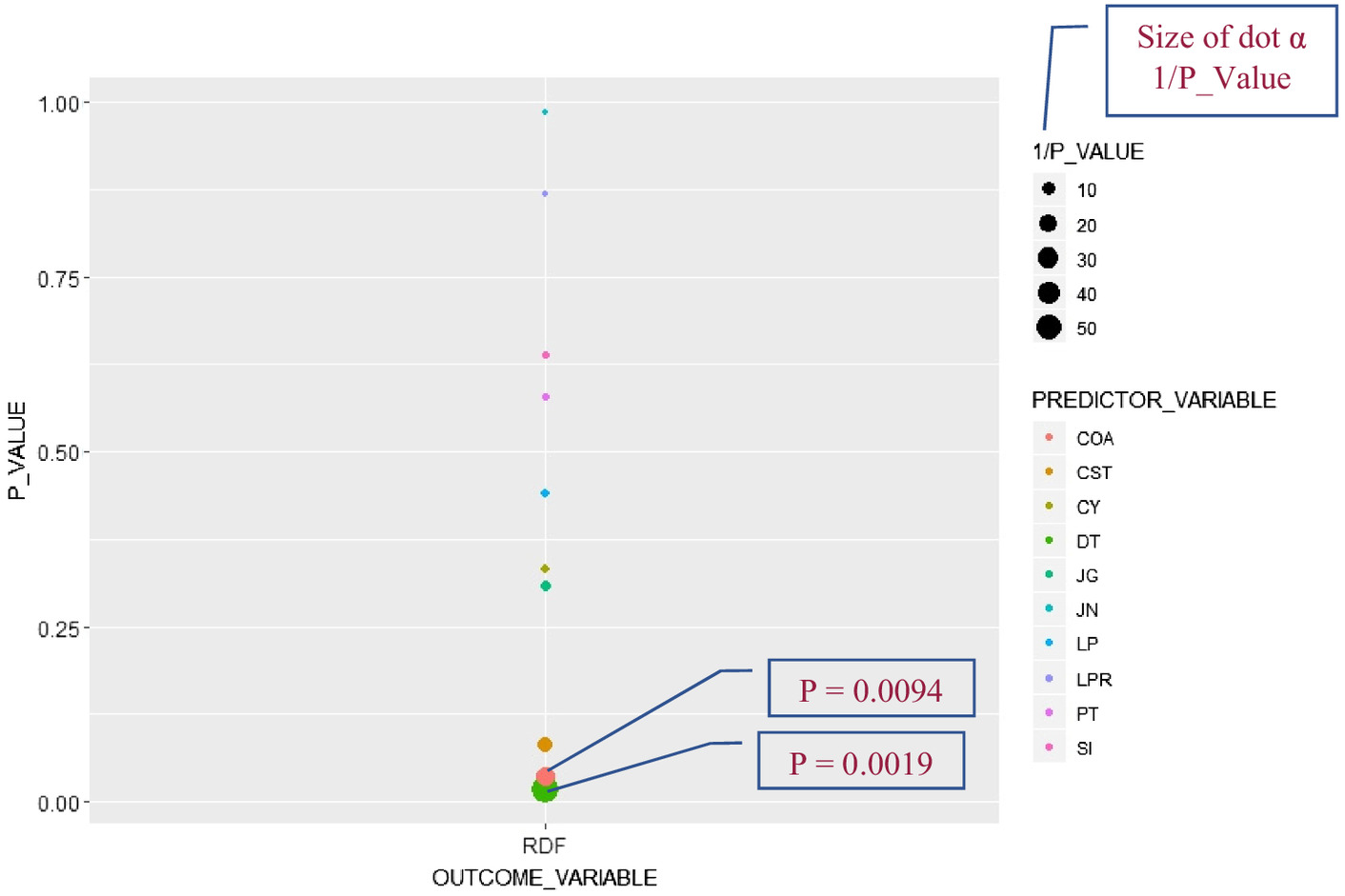

To verify the finding and interpretations of the mosaic plots, a chi-square test has been performed between one outcome variable and one predictor variable. Fig. 11 showed the outcome variable of RDF was correlating with the DT (defendant type) and COA (cause of action) with a P-value of 0.019 and 0.0094 respectively, for the cases examined. These p values proved the previous observations found in Figs. 5 and 6 respectively, where it was seen that the standardized residuals for the correlation between the RDF with defendant type and RDF with the cause of action were more than what was expected in the range between 2 to 4 standardized residuals. Thus, the null hypothesis (that COA and DT have no correlation with RDF) can be ignored for the preceding and the DRF was correlating with COA and DT as it was in Figs. 5, 6, and 11.

Conclusions

Two hundred and forty-one (241) cases were collected from the Courts of Appeals in Arizona, California, and New Mexico, containing AEC keywords. Sixty-two (62) of these cases were found to be related to the AEC industry. These cases were analyzed via qualitative analysis software to isolate eleven case variables (seven input variables and four output variables). A statistical analysis of the categorical variables was performed. The conclusions are listed as follow for these cases:

1.

When the defendant type was a government entity or agency, the ruling decision factor was evidentiary nature with a residual value (see Fig. 5). The evidence (EVD) ruling decision factor was correlated with the government (GOV) defendant type.

2.

When the cause of action was a warranty issue, the ruling decision factor was based on the contract with a residual value (see Fig. 6). The contract (CNT) ruling decision factor was correlated with the cause of action (COA) warranty (WAR).

3.

When the cause of action was an environmental concern, the court based the decision on evidence with a residual value (see Fig. 6). The evidence driving (EVD)the ruling decision factor correlated with the cause of action environmental (ENV).

4.

The gender of Judge did not affect the ruling decision factor of any specific case.

5.

The amount of legal practice/years of experience a judge had did not affect the ruling decision factor chosen by the court.

6.

Whether or not the case had a structural issue had no bearing on the ruling decision factor of a given case.

7.

The case results did not depend on the ruling decision factor (RDF) chosen by the court.

8.

The ruling decision factor (RDF) did not depend on the case state (CST).

9.

The wining party of a case; ruled in favor (RIF) of did not depend on the ruling decision factor (RDF) chosen by the court.

10.

The legal fees responsibility (LFR) did not depend on the ruling decision factor (RDF). The ruling decision factor chosen by the court did not affect whether or not the party is responsible for the legal fees.

When the cause of action was environmental in nature, the ruling decision factor tended to be of evidentiary nature. This is because the legal grounds for contract cases are different from wrongdoing (tort) cases.

The preceding conclusions provide an insight to the parties before or during litigations that shed light on the case parameters affecting or not affecting the way the court will likely choose the ruling decision factor of a given case. The research importance highlighted that understanding how the court will look at a case should affect the disputed parties’ decision whether to go through the process of litigation, or to choose other dispute resolution methods. The methodology separated four different factors that the courts took into consideration when making a ruling and showed how these factors impact the ruling decision factor. For example, if the reason for the case was warranty issue, the parties should refer to the contract and follow the terms laid out therein, because the court would follow the contract for such cases. A residual of 2.57 shows these two variables (warranty and contract) are highly correlated in a positive manner.

Future Research

This research should be expanded to track litigation trends nationally and globally. Future research can include cases that are settled in arbitration and mediation without entering litigation. Cases that settle are not made public (U.S.C, Title 9), as parties usually agree to close the case and often sign a mutual non-disclosure agreement.

Obtaining access to cases that do not enter litigation can help close the gap between alternative dispute resolution methods and litigation. In AEC arbitration cases, the arbitrator will be an individual with experience in the AEC industry, whereas in litigation, the judge might have experience in construction cases, but not likely as experienced in the AEC areas.

Limitations and Recommendations

The research was conducted using cases from Arizona, New Mexico, and California Courts of Appeals. Cases that reach this level of maturity go beyond cases of the district/superior court level. It is taken as understood that the findings and conclusions still apply to the superior/district court because the base of the appeal cases came from the superior and district courts.

Data Availability Statement

All data that have been used in this research were derived from the cases listed References (List of cases). All cases collected were available to the public via LexisNexis Legal Cases Data Base (n.d.) or other case database systems. All case data is available.

Models, or code generated or used during the study are proprietary or confidential in nature and may only be provided with restrictions. Professional software (MAXQDA) was used to analyze the data must be purchased to read the files.

References

List of Cases

Albano v. Shea Homes L.P. Supreme Court of Arizona June 30, 2011, Decided Arizona Supreme Court No. CV-11-0006-CQ (Albano v. Shea Homes L.P., 227 Ariz. 121, P. 1: 56). RSP Architects, Ltd.,) No. 1 CA-CV 12-0545 a Minnesota corporation) Plaintiff/Appellant, v.) Department C Five Star Development Resort Communities, LLC, an Arizona Limited liability company) Opinion Five Star Development Properties, LLC, an Arizona limited liability company; Five Star Development Group, Inc., an Arizona) corporation; Five Star Development Communities, LLC, an Arizona limited liability company, Defendants/Appellees. Appeal from the Superior Court in Maricopa County Cause No. CV2009-038240 (1 CA-CV 12-0545-168612, P. 1: 57).

Alvis v. County of Ventura Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division Six October 20, 2009, Filed No. B212337 (Alvis v. County of Ventura, 178 Cal. App. 4th 536, P. 1: 56).

Avalon Custom Homes, L.L.C., an Arizona limited liability company, Plaintiff/Appellant, v. Fidelis V. Garcia, Arizona Registrar of Contractors; Michael Proctor and Pamela Proctor, husband and wife, Defendants/Appellees. 1 CA-CV 08-0106 Department A Memorandum Decision Not for Publication–(Rule 28, Arizona Rules of Civil Appellant FILED 12-26-2008 Appeal from the Superior Court in Mohave County Cause No. CV 2006-1131 (1 CA-CV 08-0106-97161, P. 1: 257).

Beacon Residential Community Assn. v. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP Supreme Court of California July 3, 2014, Filed S208173 (Beacon Residential Community Assn. v. Skidmore, Owings & Merril, P. 1: 55).

Bottini v. City of San Diego Court of Appeal of California, Fourth Appellate District, Division One September 18, 2018, Opinion Filed D071670 (Bottini v. City of San Diego, 27 Cal. App. 5th 281, P. 1: 55).

C.W. Howe Partners Inc. v. Mooradian Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division Seven December 19, 2019, Opinion Filed B290665 (C.W. Howe Partners Inc. v. Mooradian, 43 Cal. App. 5th 688, P. 1: 55).

CANTEX Inc., a Delaware corporation, Plaintiff/Appellee, v. Giles Engineering Associates, Inc., Third-Party Defendant/Appellant. Nos. 1 CA-CV 15-0620 1 CA-CV 15-0631 (Consolidated) (1 CA-CV 07-0037-81818, P. 1: 216).

California Oak Foundation v. Regents of University of California Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division Three September 3, 2010, Filed A122511 (California Oak Foundation v. Regents of University of California, P. 1: 55).

Chonczynski v. Aguilera Court of Appeals of Arizona, Division One December 2, 2014, Filed No. 1 CA-CV 13-0728 [Chonczynski v. Aguilera, 2014 Ariz. App. Unpub. LEXIS 1430), P. 1: 58].

Cincinnati Indemnity Company, Plaintiff/Appellee, v. Southwester Line Constructors Joint Apprenticeship and Training Program, et al. Defendants/Appellants. No. 1 CA-CV 17-0238 (CV 17-0238, P. 1: 48).

Citizens for a sustainable Treasure Island v. City and county of San Francisco 227 Cal.App.4th 1036; 174 Cal.Rptr.3d 363 [July 2014] (Citizens for a Sustainable Treasure Island v. City and County o, P. 1: 1494).

City of Maywood v. Los Angeles Unified School Dist. Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division Seven July 18, 2012, Opinion Filed Nos. B233739, B236408 (City of Maywood v. Los Angeles Unified School Dist., 208 Cal. A, P. 1: 55).

City of Phoenix v. Glenayre Elecs., Inc. Supreme Court of Arizona May 10, 2017, Filed No. CV-16-0126-PR (City of Phoenix v. Glenayre Elecs., Inc., 242 Ariz. 139)), P. 1: 57) Northeast Phoenix Holdings, LLC v. Winkleman Court of Appeals of Arizona, Division One, Department E April 22, 2008, Filed No. 1 CA-SA 08-0011 (Northeast Phoenix Holdings, LLC v. Winkleman, 219 Ariz. 82 NR, P. 1: 58).

Construction 70, Inc., an) 1 CA-CV 10-0137 Arizona corporation, Department A Plaintiff/Appellee, Memorandum Decision v.) (Not for Publication - Rule 28, Arizona Rules of Bond Safeguard Insurance Company), Civil Appellate Procedure an Illinois corporation, Defendant/Appellant. Appeal from the Superior Court in Maricopa County Cause No. CV2008-014200 (1 CA-CV 10-0137-132092, P. 1: 252).

County of Los Angeles v. Glendora Redevelopment Project Court of Appeal of California, Sixth Appellate District June 15, 2010, Filed H032945 (County of Los Angeles v. Glendora Redevelopment Project, 185 Ca, P. 1: 56).

Damon v. StrucSure Home Warranty, LLC Court of Appeals of New Mexico August 19, 2014, Filed NO. 33,126 (Damon v. StrucSure Home Warranty, LLC, 2014-NMCA-116, P. 1: 55).

Damon v. Vista Del Norte Dev., LLC Court of Appeals of New Mexico July 12, 2016, Filed NO. 33,775 (Damon v. Vista Del Norte Dev., LLC, 2016-NMCA-083, P. 1: 56).

December 11, 2015, Opinion Filed F069953 (Vardanyan v. AMCO Ins. Co., 243 Cal. App. 4th 779, P. 1: 56).

Diana Glazer, Plaintiff/Appellant, v. State of Arizona, Defendant/Appellee. No. 1 CA-CV 16-0416 (2017-1-ca-cv-16-0416, P. 1: 48) Terry McGinnis, Plaintiff/Appellant, v. Arizona Public Service Company, Defendant/Appellee. No. 1 CA-CV 17-0486 (1 CA-CV 17-0486, P. 1: 216).

Digital Systems Engineering, Inc, Plaintiff/Appellee, v. John Moreno and Bernadette Bruce Moreno, Defendants/Appellants. 1 No. 1 CA-CV 16-0156 (2017-1-ca-cv-16-0156, P. 1: 48).

Du-All Safety, LLC v. Superior Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division Two April 18, 2019, Opinion Filed A155119 (Du-All Safety, LLC v. Superior Court, 34 Cal. App. 5th 485, P. 1: 53).

Enrique and Matilda Medina, Plaintiffs/Appellees v. Ocotillo Desert Sales LLC; Ocotillo Desert Construction, LLC, Ocotillo Desert Development, LLC; Brian L. Hall and Jane Doe Hall, husband and wife; Fred T. Hall and Jane Doe Hall, husband and wife, Defendants/Appellants 1 CA-CV 09-0650 Department C Memorandum Decision (Not for Publication Rule 28, Arizona Rules of Civil Appellate Procedure Appeal from the Superior Court in Yuma County Cause No. S1400CV200500643 (1 CA-CV 09-0650-121597, P. 1: 251).

Friends of Williamson Valley, Incorporated, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Yavapai County, a political subdivision of the State of Arizona; Carol Pinger, Thomas Thurman, and Chip Davis, in their official capacity as members of the Board of Supervisors for Yavapai County, Defendants-Appellees. 1 A-V 08-0512 Department E Memorandum Decision (Not for Publication–Rule 28, Arizona Rules of Civil Appellate Procedure) Appeal from the Superior Court in Yavapai County Cause No. CV 2007-0751 (1 CA-CV 08-0663-110137, P. 1: 257).

Gorman v. Tassajara Development Corp. Court of Appeal of California, Sixth Appellate District October 6, 2009, Filed H031196 (Gorman v. Tassajara Development Corp., 178 Cal. App. 4th 44, P. 1: 55).

Grady’s Quality Excavating, Inc., an Arizona corporation, Plaintiff/Appellant, v. Alliance Streetworks, Inc., an Arizona corporation; North American Specialty Insurance Company, a foreign corporation, Defendants/Appellees, Alliance Streetworks, Inc., an Arizona corporation, Counter - Claimant, v. Grady’s Quality Excavating, Inc., an Arizona corporation, Counter-Defendant. No. 1 CA-CV 16-0739 Appeal from the Superior Court in Yavapai County No. V1300CV201480119.

Grebow v. Mercury Ins. Co. Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division Five October 21, 2015, Opinion Filed B261172 (Grebow v. Mercury Ins. Co., 241 Cal. App. 4th 564, P. 1: 55).

In the Court of Appeals State of Arizona Division One (1 CA-CV 07-0037-81818, P. 1: 0).

Jeffrey Alan Oursland, an unmarried man; Security Lenders, Inc., an Arizona corporation, and Lawyers Title of Arizona, Inc., an Arizona corporation, formerly known as LandAmerica Title Agency, as Trustee under its Trust No. 10,002; Siegel Arizona Properties, LLC, a Utah limited liability company; Coyote Springs, LLC, an Arizona limited liability company, Petitioners, v. The Honorable David Mackey, Judge of the Superior Court of the State of Arizona, in and for the County of Yavapai, Respondent Judge, Arizona Public Service Company, an Arizona public service corporation, Real Party in Interest. No. 1 CA-SA 18-0100 (1 CA-SA 18-0100 - Oursland, P. 1: 216).

Jones v. P.S. Development Co., Inc. Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division Four September 3, 2008, Filed B198464 (Jones v. P.S. Development Co., Inc., 166 Cal. App. 4th 707, P. 1: 55).

Joseph M. Arpaio, et al. Plaintiffs/Appellants, v. Hines GS Properties, Inc., et al. Defendants/Appellees. No. 1 CA-CV 16-0781 (CV16-0781, P. 1: 216).

Joseph Painting Company, Inc. dba JPCI Services, an Arizona corporation, Plaintiff/Appellant, v. Larson Engineering, Inc, a foreign corporation dba Larson Engineering of Arizona, Defendant/Appellee. CA-CV 09-0327 Department A Memorandum Decision (Not for Publication–Rule 28, Arizona Rules of Civil Appellate Procedure) Appeal from the Superior Court in Maricopa County Cause No. CV 2006-016783 (1 CA-CV 09-0327-116442, P. 1: 257).

Lindemann v. Hume Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division Seven February 21, 2012, Opinion Filed B226106, B233273 (Lindemann v. Hume, 204 Cal. App. 4th 556, P. 1: 55).

Loranger v. Jones Court of Appeal of California, Third Appellate District April 23, 2010, Filed C061517 (Loranger v. Jones, 184 Cal. App. 4th 847, P. 1: 55).

MTR Builders, Inc., an Arizona corporation, Plaintiff/Counter Defendant/Appellee/Cross-Appellant, v. Jahan Realty Management Corporation, Defendant/Counterclaimant/Appellant/Cross-Appellee. No. 1 CA-CV 14-0650 (1 CA-CV 14-0650, P. 1: 219).

Martinez v. N.M. DOT Court of Appeals of New Mexico June 1, 2011, Filed Docket No. 28,661 Martinez v. N.M. DOT, 150 N.M. 204, P. 1: 55) Supreme Court of the United States, 2019.

Mary C. Boruch, an individual; et al. Plaintiffs/Appellants, v. State of Arizona ex rel. John Halikowski, Director of the Arizona Department of Transportation; the City of Mesa, an Arizona municipal corporation, Defendants/Appellees. No. 1 CA-CV 15-0534 Appeal from the Superior Court in Maricopa County No. CV2014-014115 (2017-1-ca-cv-15-0534, P. 1: 48).

McAllister v. California Coastal Com. Court of Appeal of California, Sixth Appellate District December 30, 2008, Filed H031283 (McAllister v. California Coastal Com., 169 Cal. App. 4th 912, P. 1: 55).

Meritage Homes of Arizona, Inc., an Arizona corporation Plaintiff/Appellee, v Bingham Engineering Consultants, LLC, an Arizona limited liability corporation, Defendant/Appellant. No. 1 CA-CV 13-0072 (CA-CV13-0072, P. 1: 216).

Moore v. Teed Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division One April 24, 2020, Opinion Filed A153523 (Moore v. Teed, 48 Cal. App. 5th 280, P. 1: 55).

Myrick v. Mastagni Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division Six June 21, 2010, Filed B209854 (Myrick v. Mastagni, 185 Cal. App. 4th 1082, P. 1: 55).

North Counties Engineering, Inc. v. State Farm General Ins. Co. Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division Two March 13, 2014, Opinion Filed A133713 (North Counties Engineering, Inc. v. State Farm General Ins. Co., P. 1: 55).

Oak Springs Villas Homeowners Assn. v. Advanced Truss Systems, Inc. Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division Eight June 14, 2012, Opinion Filed B234568 (Oak Springs Villas Homeowners Assn. v. Advanced Truss Systems, P. 1: 55).

Oakland Heritage Alliance v. City of Oakland Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division Four May 19, 2011, Filed A126558 (Oakland Heritage Alliance v. City of Oakland, 195 Cal. App. 4th, P. 1: 55).

Oldcastle Precast, Inc. v. Lumbermens Mutual Casualty Co. Court of Appeal of California, Fourth Appellate District, Division Three January 23, 2009, Filed G038645 (Oldcastle Precast, Inc. v. Lumbermens Mutual Casualty Co., 170, P. 1: 56).

Paulek v. Department of Water Resources Court of Appeal of California, Fourth Appellate District, Division Two October 31, 2014, Opinion Filed E060038 (Paulek v. Department of Water Resources, 231 Cal. App. 4th 35, P. 1: 53).

Peter T. Else, Plaintiff/Appellant, v. Arizona Corporation Commission, Defendant/Appellee, Sunzia Transmission LLC, Intervenor/Appellee. No. 1 CA-CV 17-0208 (1 CA-CV 17-0208, P. 1: 216).

Pueblo Santa Fe Townhomes Owners’ Ass’n v. Transcon. Ins. Co. Court of Appeals of Arizona, Division One, Department B March 13, 2008, Filed No. 1 CA-CV 07-0215 (Pueblo Santa Fe Townhomes Owners’ Ass’n v. Transcon. Ins. Co., P. 1: 55).

RSB Vineyards, LLC v. Orsi Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division Three September 29, 2017, Opinion Filed A143781, A145029 (RSB Vineyards, LLC v. Orsi, 15 Cal. App. 5th 1089, P. 1: 53).

Regional Steel Corp. v. Liberty Surplus Ins. Corp. Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division One May 16, 2014, Opinion Filed B245961 (Regional Steel Corp. v. Liberty Surplus Ins. Corp., 226 Cal. Ap, P. 1: 55).

SI 59 LLC v. Variel Warner Ventures, LLC Court of Appeal of California, Second Appellate District, Division Two November 15, 2018, Opinion Filed B285086 (SI 59 LLC v. Variel Warner Ventures, LLC, 29 Cal. App. 5th 146, P. 1: 56).

Saguaro Highlands Cmty. Ass’n v. Biltis Court of Appeals of Arizona, Division One, Department C May 6, 2010, Filed No. 1 CA-CV 09-0261 (Saguaro Highlands Cmty. Ass’n v. Biltis, 224 Ariz. 294NR, P. 1: 57).

Seahaus La Jolla Owners Assn. v. Superior Court of Appeal of California, Fourth Appellate District, Division One March 12, 2014, Opinion Filed D064567 (Seahaus La Jolla Owners Assn. v. Superior Court, 224 Cal. App., P. 1: 55).

Sequoia Park Associates v. County of Sonoma Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division Two August 21, 2009, Filed A120049 (Sequoia Park Associates v. County of Sonoma, 176 Cal. App. 4th, P. 1: 55).

Shasta Industries Inc., Plaintiff/Appellee, v. Samuel Jepson Sutton II, et al. Defendants/Appellants. No. 1 CA-CV 17-0063 Appeal from the Superior Court in Maricopa County No. CV2016-002714.

Shawn and Penny Edwards, husband) 1 CA-CV 08-0427 and wife,)Department B Plaintiffs/Appellants, Opinion v. Board of Supervisors of Yavapai County, a political subdivision of the State of Arizona; and Yavapai County Flood Control District, a political subdivision of the State of Arizona, Defendants/Appellees. Appeal from the Superior Court in Yavapai County Cause No. P-1300-CV-0020050640 (1 CA-CV 08-0427-117500, P. 1: 60).

Southwest Concrete Paving Co., Plaintiff/Appellee/Cross-Appellant, v. SBBI, Inc., et al. Defendants/Appellants/Cross-Appellees. No. 1 CA-CV 17-0294 (1 CA-CV 17-0294, P. 1: 217).

State of California v. Allstate Ins. Co. Supreme Court of California March 9, 2009, Filed S149988 (State of California v. Allstate Ins. Co., 45 Cal. 4th 1008, P. 1: 55).

Stofer v. Shapell Industries, Inc. Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division Five January 15, 2015, Opinion Filed A139385 (Stofer v. Shapell Industries, Inc., 233 Cal. App. 4th 176, P. 1: 56).

Vardanyan v. AMCO Ins. Co. Court of Appeal of California, Fifth Appellate District.

Zumar Industries, Inc., Plaintiff/Appellee, v. Caymus Corporation, Defendant/Appellant. No. 1 CA-CV 16-0423 (2017-1-ca-cv-16-0423, P. 1: 48).

1800 OCOTILLO, LLC, an Arizona limited liability company, Plaintiff/Appellant, v. The WLB Group, Inc., an Arizona corporation, Defendant/Appellee. No. 1 CA-CV 07-0037 Department B Opinion FILED 1-29-08 (1 CA-CV 07-0037-81818, P. 1: 60).

1800 Ocotillo, LLC v. WLB Group, Inc. Court of Appeals of Arizona, Division One, Department B January 29, 2008, Filed No. 1 CA-CV 07-0037 (1800 Ocotillo, LLC v. WLB Group, Inc., 217 Ariz. 465, P. 1: 57).

1800 Ocotillo, LLC v. WLB Group, Inc. Supreme Court of Arizona November 03, 2008, Decided Arizona Supreme Court No. CV-08-0057-PR (1800 Ocotillo, LLC v. WLB Group, Inc., 219 Ariz. 200, P. 1: 57).

List of Statutes

United States Constitution and federal status, U.S.C Code 9 (Arbitration).

Works Cited

AACE (Association for the Advancement of Cost Engineering). 2012. “Rose fulbright, 2016 litigation trends survey.” Accessed October 12, 2020. https://www.pathlms.com/aace/courses/2926/video_presentations/34404Norton.

Arditi, D., and T. Pattanakitchamroon. 2008. “Analysis methods in time-based claims.” J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 134 (4): 242–252. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3801(2009)23:3(178).

Arditi, D., and T. Pulket. 2005. “Predicting the outcome of construction litigation using boosted decision trees.” J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 19 (4): 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3801(2005)19:4(387).

Arditi, D., and T. Pulket. 2009. “Predicting the outcome of construction litigation using an integrated artificial intelligence model.” J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 24 (1): 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3801(2010)24:1(73).

Awwad, R., and P. Ioannou. 2012. “A risk-sensitive markup decision model.” In Proc., Construction Research Congress 2012: Construction Challenges in a Flat World, 199–208. Reston, VA: ASCE. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784412329.021.

Barry, B. M. 2023. How Judges judge: Empirical insights into judicial decision-making. Oxfordshire, UK: Taylor & Francis.

Cooper, R., R. Nelson-Williams, G. Kitt, J. Recan, and M. Torres. 2018. Global construction disputes report 2018. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Arcadis.

Cran. n.d. “The Comprehensive R Archive Network.” Accessed October 12, 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/.

Di Leo, G., and F. Sardanelli. 2020. “Statistical significance: P-value, 0.05 threshold, and applications to radiomics—Reasons for a conservative approach.” Eur. Radiol. Exp. 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41747-020-0145-y.

Fisher, R. A. 1925. Statistical methods for research workers, biological monographs and manuals, Oliver and Boyed great Britain. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Gad, G. M. 2012. Effect of culture, risk, and trust on the selection of dispute resolution methods in international construction contracts. Ames, IA: UMI-Dissertation Publishing.

Gad, G. M., and J. S. Shane. 2012. “A delphi study on the effects of culture on the choice of dispute resolution methods in international construction contracts.” In Proc., Construction Research Congress 2012: Construction Challenges in a Flat World, 1–10. Reston, VA: ASCE. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784412329.001.

Greenland, S., S. J. Senn, K. J. Rothman, J. B. Carlin, C. Poole, S. N. Goodman, and D. G. Altman. 2016. “Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: A guide to misinterpretations.” Eur. J. Epidemiol. 31 (4): 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0149-3.

Griego, R., and F. Leite. 2016. “Premature construction start interruptions: How awareness could prevent disputes and litigations.” J. Leg. Aff. Dispute Resolut. Eng. Constr. 9 (2): 04516016. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)LA.1943-4170.0000210.

Kululanga, G. K., W. Kuotcha, R. McCaffer, and F. Edum-Fotwe. 2001. “Construction contractors’ claim process framework.” J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 127 (4): 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)0733-9364(2001)127:4(309).

LexisNexis Legal Cases Data Base. n.d. “Portals for computer-assisted legal research, newspaper search, and consumer information.” Accessed April 28, 2022. https://www.lexisnexis.com/.

Mahfouz, T., and A. Kandil. 2009. “Factors affecting litigation outcomes of differing site conditions (DSC) disputes: A logistic regression models (LRM).” In Construction research congress 2009: Building a sustainable future. Reston, VA: ASCE. https://doi.org/10.1061/41020(339)25.

Mahfouz, T., and A. Kandil. 2011. “Litigation outcome prediction of differing site condition disputes through machine learning models.” J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 26 (3): 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CP.1943-5487.0000148.

Niu, J., and R. R. Issa. 2014. “Rule-based NLP methodology for semantic interpretation of impact factors for construction claim cases.” In Computing in civil and building engineering, 2263–2270. Reston, VA: ASCE. https://doi.org/10.1061/9780784413616.281.

Pastrana, T., L. De Lima, K. Pettus, A. Ramsey, G. Napier, R. Wenk, and L. Radbruch. 2021. “The impact of covid-19 on palliative care workers across the world: A qualitative analysis of responses to open-ended questions.” Palliative Supportive Care 19 (2): 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951521000298.

Saeidi, S., Z. Xu, Y. Zhu, S. Mukhopadhyay, and R. Gudishala. 2019. “Application of virtual reality to investigate driver’s route choice in an interstate freeway.” In Proc., ASCE Int. Conf. on Computing in Civil Engineering 2019, 129–136. Reston, VA: ASCE.

Supreme Court of the United States Home. n.d “Home-Supreme Court of the United States.” Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.supremecourt.gov/.

Wasserstein, R. L., and N. A. Lazar. 2016. The ASA statement on p-values: Context, process, and purpose. Oxfordshire, UK: Taylor and Fancies.

Zavarella, L. 2018. “Toward data since.” Accessed May 1, 2022. https://towardsdatascience.com/.

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Copyright

This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

History

Received: Apr 14, 2023

Accepted: Sep 7, 2023

Published online: Nov 10, 2023

Published in print: Feb 1, 2024

Discussion open until: Apr 10, 2024

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Download citation

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.