Changes in Social Capital during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from Singapore and Switzerland

Abstract

Social capital (SC) is a key factor of social resilience and is crucial for effective crisis response and recovery. The unprecedented levels of social distancing measures during the global Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic limited social interactions and restricted traditional support channels. This has raised the question of whether such measures may have negatively impacted SC. However, few studies have analyzed SC changes over time, in representative samples and during pandemic contexts. This study assessed SC changes during the COVID-19 pandemic among representative groups of adults living in Singapore (total ) and Switzerland (total ), respectively. We assessed changes in SC, specifically in horizontal SC (i.e., ties between individuals) and vertical SC (i.e., ties between individuals and decision makers), between June 2020 and July 2021. Respondents were recruited from Qualtrics’ panels by employing quota sampling according to Singapore’s and Switzerland’s population censuses. Key results show that the overall horizontal SC increased significantly (although modestly) in both countries. Overall vertical SC increased significantly (also modestly) in Singapore and had no significant change in Switzerland. All analyses were performed in R software (version 4.2.2). Thus, despite social distancing measures, horizontal SC and vertical SC indicators remained stable in both countries. Further studies may be warranted to determine the causal pathways involved in retaining SC in pandemic settings.

Practical Applications

During the COVID-19 pandemic with social distancing measures, horizontal and vertical social capital remained stable, with no losses, in both Singapore and Switzerland. This may potentially indicate sustained social resilience. Evidence-based measures tailored to the value system of a country and the innovative, adaptive capacities of residents may have partly contributed toward the stability of social capital. Policymakers and relevant agencies working in social resilience could potentially benefit from increasing tailored communication and messaging efforts to maintain social capital, which may serve as important insurance in case of future pandemics.

Background

Social capital (SC), i.e., social ties that enable connections, trust, mutual aid, or collective action (Fraser and Aldrich 2021), has been identified widely as a dominant and crucial dimension of social resilience (Kwok et al. 2016; Saja et al. 2018). Both horizontal SC (i.e., ties between individuals of similar status and power within a community) and vertical SC (i.e., ties between individuals and decision makers or authorities) (Aida et al. 2009; Bhandari and Yasunobu 2009) at local and national levels are important for effective coping, response, and recovery during and after crises (Aldrich and Meyer 2015; Kwok et al. 2016).

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) led to the declaration of a global pandemic in March 2020, and almost all countries worldwide implemented social distancing measures such as travel restrictions, citywide lockdowns, extensive quarantines, school closures, and soft public health messaging (Onyeaka et al. 2021). The unprecedented levels and protracted duration of social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited physical interactions and traditional channels of social support, raise the question of whether these measures may have triggered a decrease in SC (Pitas and Ehmer 2020). Understanding changes in SC due to social distancing measures is crucial for assessing the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and gaining insights into the potential consequences of future pandemics (Sun et al. 2022). Such insights are important because a decrease in SC might decrease a country’s social resilience by reducing compliance with mandates (Barrios et al. 2021), disrupting information dissemination, increasing frequent risky behaviors, or diminishing capacities for recovery or response in future crises (Kwok et al. 2016).

However, few studies have analyzed changes in SC over time while social distancing measures were in place. Although SC changes in the contexts of natural disasters (Saja et al. 2018; Layla et al. 2020) or financial crises (Lindström and Giordano 2016) have been well studied, there is limited applicability of these studies to the COVID-19 pandemic context (Busic and Schubert 2022) because they typically do not consider limitations to social interactions between individuals. An established framework is lacking for assessing SC in pandemic contexts (Layla et al. 2020) with prolonged limits on physical interactions. Existing studies of SC during the COVID-19 pandemic largely have been limited to single SC indicators (Borkowska and Laurence 2021; Yu et al. 2021; Tatarko et al. 2022) or specific segments of populations (e.g., only students, workers, or the elderly) (Yu et al. 2021; Saraniemi et al. 2022; Sato et al. 2022). Some studies have shown that societies with higher collectivistic orientation (CO) had higher compliances with social-distancing rules and better health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (Biddlestone et al. 2020; Shekriladze et al. 2021). However, the relationship between SC changes during a pandemic crisis and the levels of collectivistic orientation (Beilmann and Realo 2012) rarely have been evaluated.

In summary, there is an evidence gap on changes in both horizontal and vertical SC over time during a pandemic for representative population samples as well as for groups with differing levels of collectivistic orientation. This study closes these gaps. Changes in SC were assessed using two waves of cross-sectional surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic, administered to adult representative samples in two countries, i.e., Singapore and Switzerland. These two chosen are characterized by similar population size, income conditions, high quality of education, and similar economic and political stability (Guo and Woo 2016), but different pandemic-related interventions. The analyses for each country comprised three parts. First, changes in horizontal SC (between residents) were assessed; second, changes in vertical SC (between residents and leaders) were assessed; and third, horizontal and vertical SC changes for groups with different levels of collectivistic orientations were investigated.

Methods

Study Design

Two waves of representative cross-sectional surveys were administered (June 2020 and July 2021) in Singapore ( in total: first wave, ; and second wave, ) and Switzerland ( in total: first wave, ; and second wave, ). The initial wave of data collection took place in June 2020, immediately after the first rounds of nationwide lockdowns in both countries were over (between April and June 2020 in Singapore, and between March and April 2020 in Switzerland), but with social distancing rules remaining in place (Federal Council 2020; Pleninger et al. 2022; Prime Minister’s Office Singapore 2023). The second wave of data collection took place 1 year after the first wave (July 2021), to allow for a sufficiently long interval between the two waves of SC assessments. Different sets of respondents were recruited in each of the two survey waves. Between the two waves of data collection (and as of July 2021), social distancing measures were of varied stringency but remained in force in both countries.

Study Population

In both waves of data collection, respondents were recruited using a specialized commercial survey sampling and administration company, Qualtrics, which manages a large online panel of respondents. Qualtrics invited respondents at random from their panel to participate via email blasts. Respondents who met the requirements of the specified demographic quotas and subsequently consented to participate were recruited, which ensured that samples were representative samples of general populations. In our study, each respondent was compensated with approximately USD 10 for their time. All respondents participated on a voluntary basis and provided their informed consent. Ethics approval was obtained from the ETH Zurich Ethics Commission (Project number 2019-N-162). This study adhered to the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration.

Both waves of surveys were web-based and were administered to representative adult samples. The samples were recruited based on sampling quotas that were representative of the respective populations with regard to gender, age, ethnicity (in Singapore), or primary national language (in Switzerland) (Federal Statistical Office 2017; Department of Statistics Singapore 2021; Federal Statistical Office 2022). Based on published population statistics, the Singapore population comprises four major ethnicity groups (76% Chinese, 15% Malays, 7% Indians, and 2% others), and has approximately equal distribution with regard to gender (45% males) and age group categories (approximately equal proportions in each 10-year age step between 20 and 69 years) (Department of Statistics Singapore 2021). The Swiss population comprises four major national languages (63% German, 23% French, 8% Italian, and 6% others) (Federal Statistical Office 2017), and has also an approximately equal distribution with regard to gender (49% males) and age group categories (approximately equal proportions in each 10-year age step between 20 and 59 years, and a slightly higher proportion (approximately) 25% for ) (Federal Statistical Office 2022). In both survey waves, the sample distribution in the two countries largely corresponded to the aforementioned population distributions.

Indicators for Social Capital

Because both horizontal SC and vertical SC are important for response and recovery during a crisis, including a pandemic, this study incorporated measures from both dimensions (Aida et al. 2009; Bhandari and Yasunobu 2009). Horizontal SC was assessed using the widely referenced main indicators of social cohesion, social networks, and social support (Saja et al. 2018; Busic and Schubert 2022; De Jesus et al. 2023). Social cohesion describes the extent of connectedness and solidarity among different groups in society, and comprised subindicators of social bonds (connectedness among community members), social trust (perceptions of reliance on members), and place attachment (feelings of belonging to a community) (Comstock et al. 2010; Aldrich and Meyer 2015; Jennings and Bamkole 2019). Social networks describe ties that generate benefits for individuals or social groups through group membership (Bourdieu 1986), and comprised subindicators on the levels of community engagement (e.g., participation or organization of community events) and the size and strength of social networks (Sharifian et al. 2019). Social support describes behaviors of receiving and giving (e.g., helping others or sharing resources) and comprised subindicators of help exchange and volunteerism (Chen et al. 2021b).

Vertical SC was assessed using the main indicators of residents’ ties with government and local leaders (Szreter and Woolcock 2004; Aida et al. 2009; Bhandari and Yasunobu 2009). Ties with government leaders comprised subindicators of vertical trust in, perceptions of, and levels of compliance with government leaders (Szreter and Woolcock 2004; Bhandari and Yasunobu 2009). Similarly, ties with local leaders comprised subindicators of vertical trust in and perceptions of local leaders (Bhandari and Yasunobu 2009). Levels of compliance with local leaders were not assessed, because this was less applicable to the Singapore context, in which pandemic measures were legislated largely by government leaders.

In both Singapore and Switzerland, respondents were presented with a standardized questionnaire and asked to indicate their perceived levels of agreement with each of the 44 response items using a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 indicated strongly disagree, 3 indicated neutral, and 5 indicated strongly agree). The mean score for each horizontal and vertical SC subindicator was averaged over the corresponding equally weighted response items. Next, mean scores for each horizontal and vertical SC main indicator were computed by taking the average score of its corresponding equally weighted subindicators. Subsequently, the mean scores for horizontal SC and for vertical SC were computed, using the average scores of its corresponding equally weighted main indicators. A higher total score indicated a higher SC level.

Further Indicators

As mentioned previously, the third goal of our study was to examine changes in SC for groups with different levels of collectivistic orientation during the period of social distancing. In the absence of a gold standard to define collectivistic values (Realo and Allik 2009), two indicators were used as proxies for the level of collectivistic orientation, namely “work for the common good/well-being” (Triandis 2019) and “stand together for our nation” (Realo et al. 1997). Respondents were asked to indicate the level of importance attached to these two collective values on a labelled response scale. This scale included the following response options: 1 = not important; 2 = somewhat important; 3 = important; 4 = very important; and 5 = highly important. Based on the average scores of the two collectivistic value indicators, we defined high and low collectivistic orientations, depending on whether the respondents’ mean scores were 4 or above (high) or less than 3 (low).

Additional indicators that were assessed in the questionnaires in both waves were sociodemographic indicators, including age, gender, ethnicity, and primarily spoken national language.

Statistical Analyses

Based on the data collected, measurements of SC in Wave 2 were compared with SC measurements in Wave 1. The changes in horizontal SC and vertical SC (and the corresponding SC main indicators) were defined as the average score in the second wave (July 2021) minus that in the first wave (June 2020). For both analyzed countries, these comparisons indicate measurements of changes in SC that might have been brought about by the implementation of social distancing rules during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comparisons between the two waves were made using Student’s -test or, if samples had unequal variances, Welch’s -test. SC changes were compared only within each analyzed country, but not between countries, because the perceptions of the different steps of the Likert scale for each response item cannot be assumed to be identical across the two countries.

To assess whether changes in horizontal SC and vertical SC differed between groups with different levels of collectivistic orientation (high or low), two-way ANOVA analyses were performed. In these analyses, the SC indicator was taken as the dependent variable, and the collectivistic orientation level and the survey time-point were taken as the independent variables. Respondents with collectivistic orientation scores in the midpoint range (equal to or greater than 3 but below 4) were excluded from the analyses to better distinguish between strong agreement or disagreement with the collectivistic orientation values items.

SC changes between different sociodemographic groups (in terms of gender, age, ethnicity, and primarily spoken national language) were assessed further using two-way ANOVA analyses. Post hoc comparisons of differences in means between waves and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each group were analyzed using independent two-sample -tests. Two-sided were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2).

Results

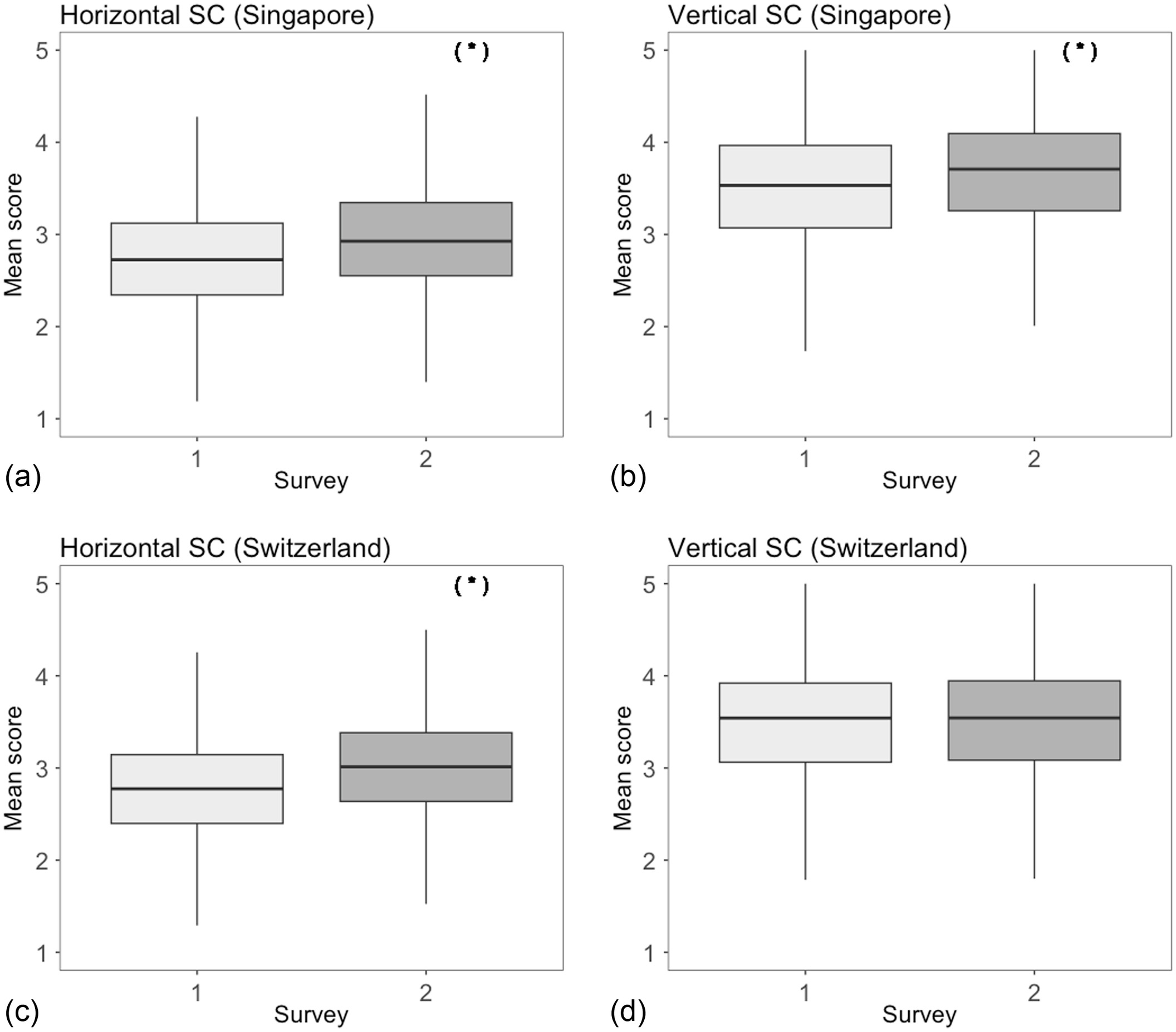

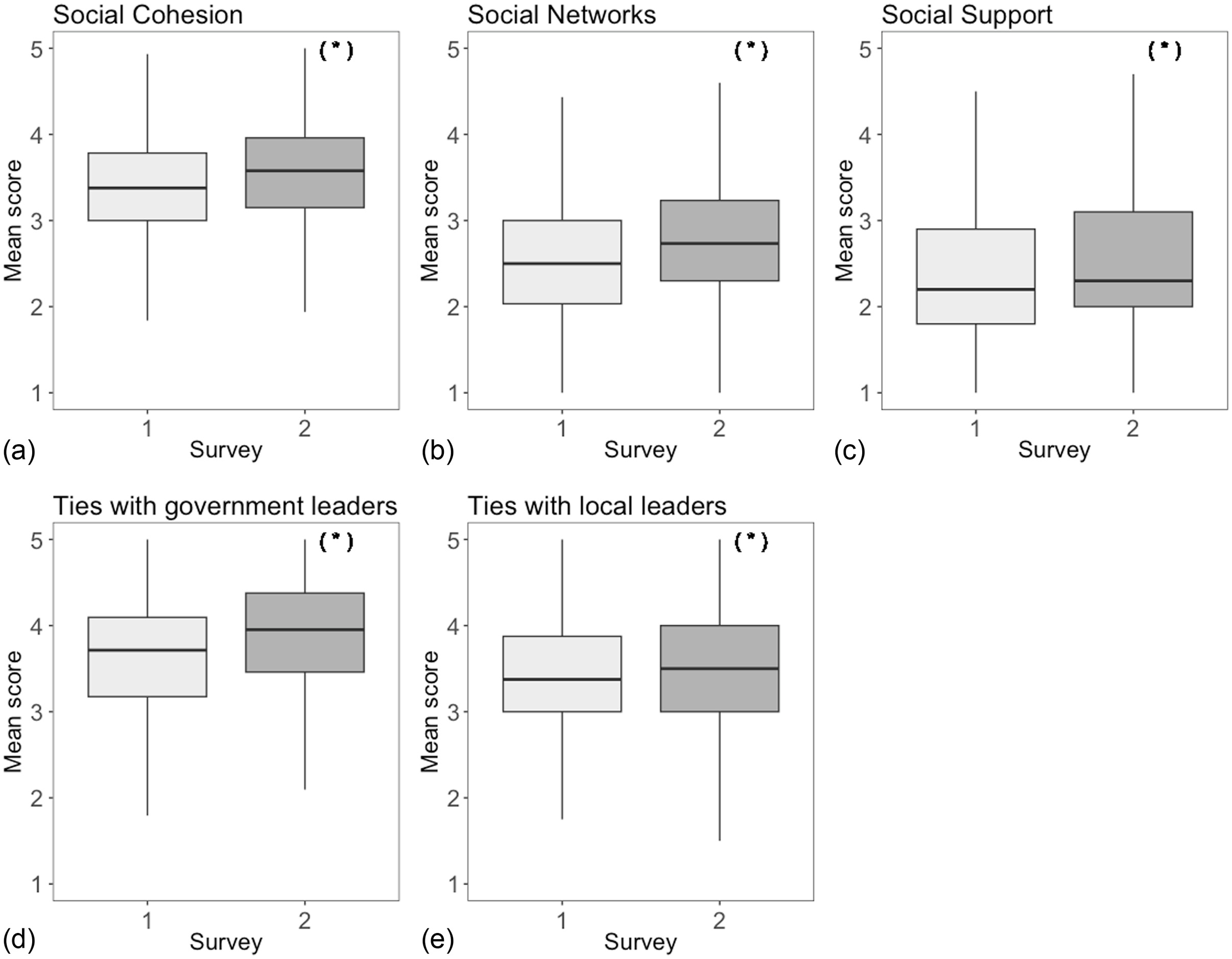

We first analyzed changes in overall SC from Wave 1 to Wave 2. Fig. 1 shows a significant increase in the overall horizontal and vertical SC for Singapore ( for all) during the pandemic (between June 2020 and July 2021), with social distancing measures in place. In Switzerland, the horizontal SC mean score increased significantly (), but the vertical SC had no significant changes (). However, the magnitudes of the significant SC increases in Singapore, and of the significant horizontal SC increase in Switzerland, were modest (Table S1 ).

Second, we analyzed changes in the main SC indicators. For Singapore, the horizontal SC main indicators, including social cohesion, social network, and social support, increased significantly during the pandemic (between June 2020 and July 2021), despite social distancing measures being in place ( for all) (Fig. 2). Similarly, the vertical SC main indicators, including ties with government leaders and ties with local leaders, increased significantly in Singapore during the pandemic ( for all), in spite of the prevalent social distancing measures (Table S1 ).

In Switzerland, the horizontal SC main indicators, including social cohesion, social network, and social support, increased significantly during the pandemic (between June 2020 and July 2021), in parallel with social distancing measures in place ( for all) (Fig. 3). However, similar to Singapore, the significant changes in horizontal SC main indicators were modest (Table S1 ). The vertical SC main indicators, including ties with government leaders () and ties with local leaders (), did not change significantly during the pandemic in Switzerland.

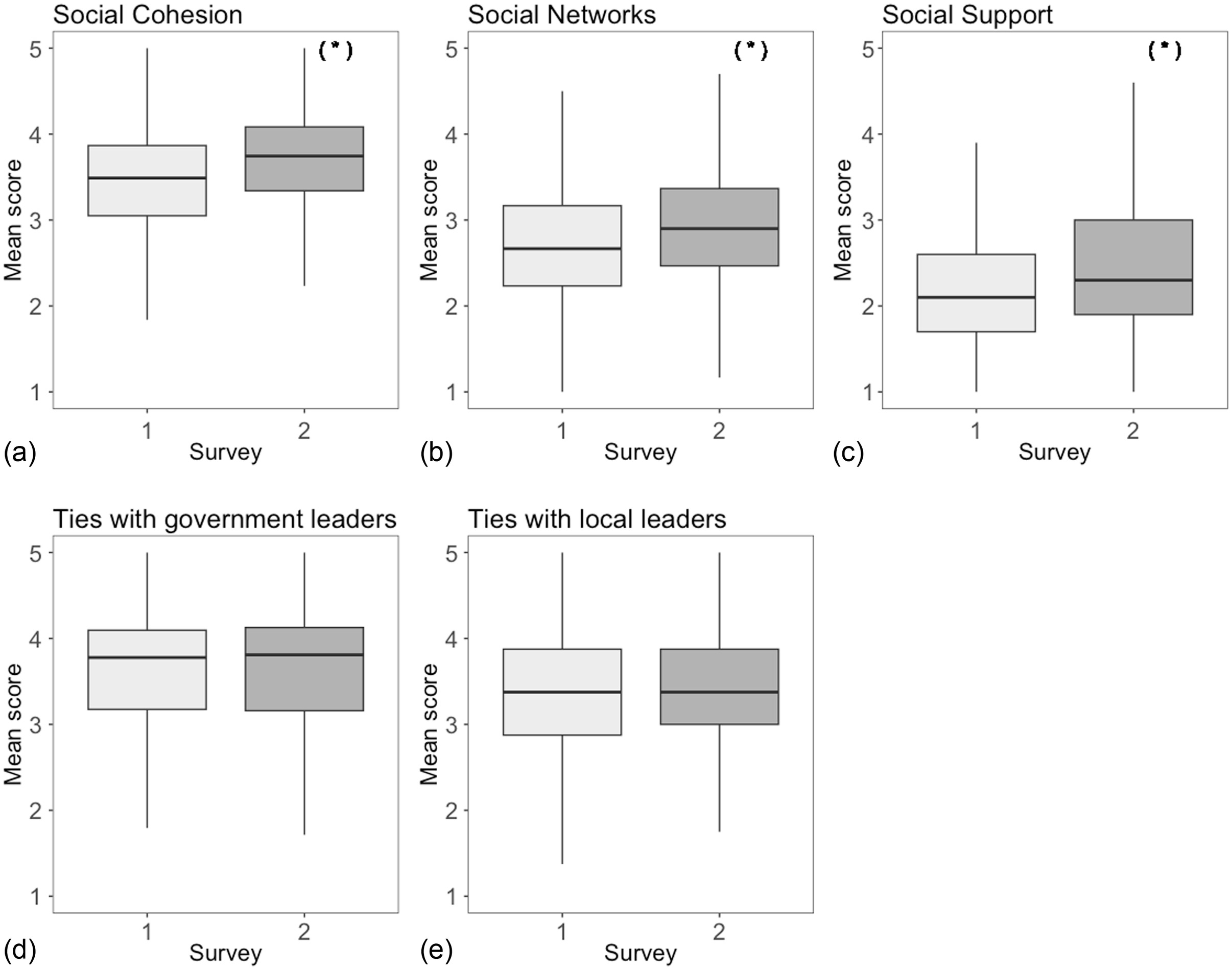

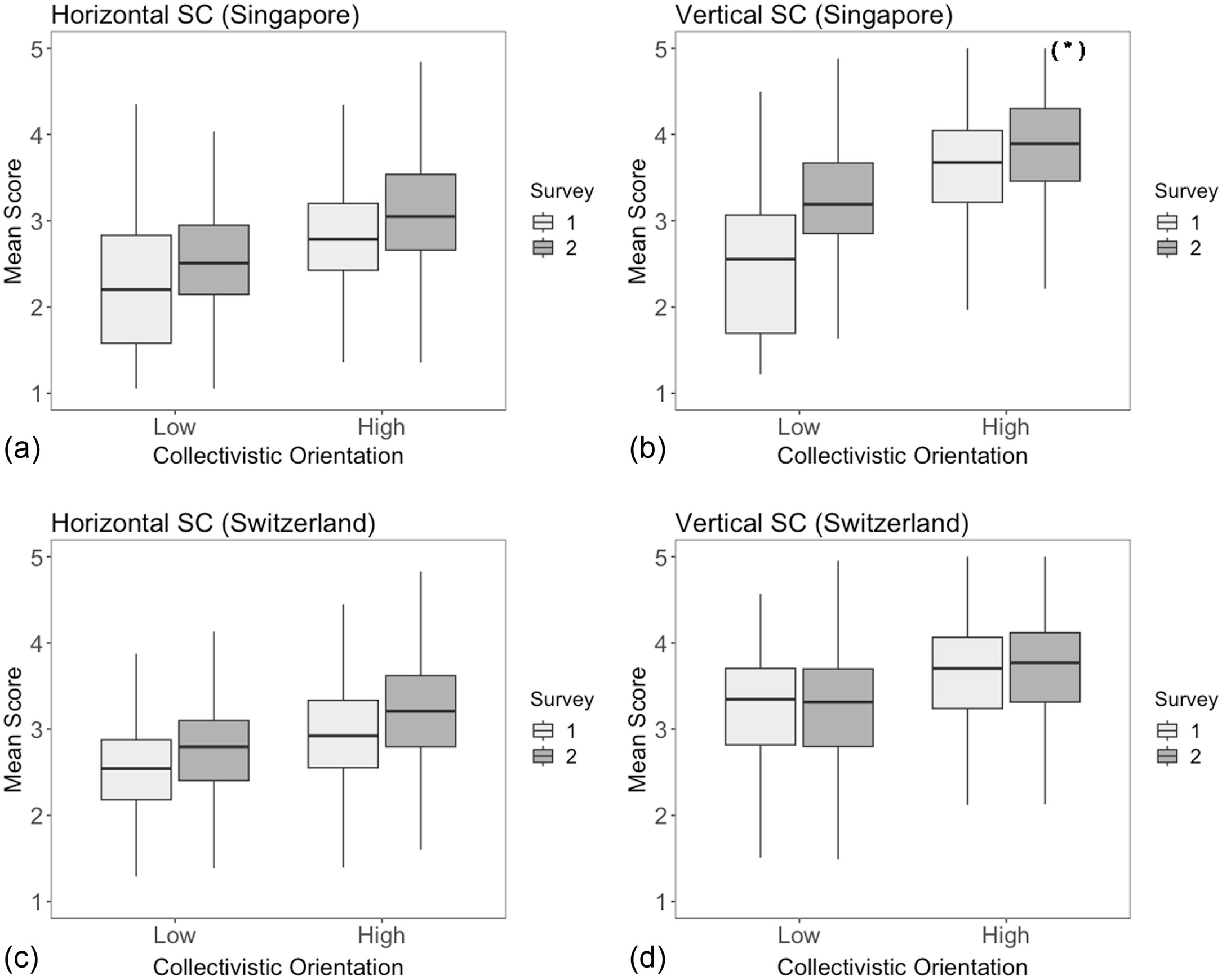

Thirdly, we analyzed the effects of citizens’ collectivistic orientation on SC changes. Both Singapore’s and Switzerland’s respondents with higher collectivistic orientation had a significantly higher mean score for overall horizontal and vertical SC compared with those with lower collectivistic orientation ( for all) (Fig. 4). Singaporean respondents with either low or high collectivistic orientation had significant positive changes (i.e., increases) in both horizontal SC and vertical SC ( for all) in the presence of social distancing measures (Table S2 ). Swiss respondents with either low or high collectivistic orientation also had significant positive changes (i.e., increases) in horizontal SC ( for all), but there were no significant changes in vertical SC in both collectivistic orientation groups ( for all).

Furthermore, we found for Singapore a significantly larger increase in vertical SC among respondents with low collectivistic orientation compared with those with high collectivistic orientation () [Fig. 4(b)]. However, the extent of changes in horizontal SC in Singapore did not vary by the levels of collectivistic orientation (). In Switzerland, the changes in overall horizontal SC and vertical SC did not differ significantly with the levels of collectivistic orientation ( for all) (Table S2 ).

We further assessed the effects of sociodemographic variables on horizontal and vertical SC changes. In Singapore, changes in horizontal SC and vertical SC did not differ between gender and ethnicity groups ( for all). However, there were differences, although modest, between age groups for horizontal SC () and vertical SC changes (). All age groups had significant increases in horizontal SC and vertical SC, except the age group 50–59 years with respect to horizontal SC changes and the age group 40–49 years with respect to vertical SC changes (Table S3 ). In Switzerland, horizontal and vertical SC changes did not differ significantly between gender or age groups ( for all). Horizontal SC changes also did not differ between language groups (), but there were modest differences between language groups with respect to vertical SC changes (). Italian speakers had a small but significant increase in vertical SC, but no significant changes were observed for other language groups ( for all) (Table S3 ).

Discussion

Key findings from this study are that horizontal and vertical SC remained stable in Singapore and Switzerland during the pandemic crisis (between June 2020 and July 2021), even while social distancing measures were in place. In both countries, overall horizontal SC and all horizontal SC main indicators had small but significant increases. Overall vertical SC and all vertical SC main indicators increased significantly and modestly in Singapore, but did not undergo significant changes in Switzerland.

The finding that overall there were no losses in SC in the presence of social distancing interventions in both countries is an encouraging result. The ability of a country to retain stable SC levels may be seen as an important insurance in the event of similar future pandemics, which might again require social distancing interventions (Bartscher et al. 2021). Although the findings of this study do not provide causal evidence, we offer a few plausible explanations for these findings, which may be explored further in future studies.

First, the increase in horizontal SC and horizontal SC main indicators, including social cohesion, social support, and social networks may have resulted partly from experiences of isolation and stress due to social distancing mandates during the pandemic. Individuals may have become more aware of the importance of mutual support, more worried about people in their networks, or more supportive of one another (e.g., checking on sick neighbors or making phone calls to friends to minimize their feelings of isolation) (Bartscher et al. 2021; Tatarko et al. 2022). Furthermore, it has been suggested that communities comprising individuals who are innovative in creating new ways or modes of collaboration to stay well connected could better share information or resources (Aldrich 2010), and hence provide more-reliable or -adequate assistance to group members (Fraser and Aldrich 2021). Social media platforms have been reported to maintain social support systems when physical contact is challenged, through the expansion or activation of individuals’ social networks beyond existing networks and the linkage of resources from local and central governments to community members (Page-Tan 2021; Samutachak et al. 2023). The significant increases in overall horizontal SC in both Singapore and Switzerland thus may reflect the abilities of individuals to invent and adapt to new ways of expediting collective action, connection, and interaction with their group members or leaders during a pandemic, when social distancing rules limit physical contact. The stable horizontal SC in Singapore and Switzerland found in this study concurs with findings from a cross-sectional study of 10,540 Chinese youths (Yu et al. 2021). Conversely, a cross-sectional study of 500 Russian adult respondents reported a decrease in social cohesion with distancing measures (Tatarko et al. 2022). However, the explanatory power of both the Chinese and Russian studies may be limited because the assessment of SC was implemented only at a single point in time.

Second, consistent across Singapore and Switzerland, vertical SC remained stable when social distancing measures were in place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Whereas vertical SC remained unchanged in Switzerland, it increased significantly (although modestly) in Singapore. The stability of vertical SC in the two countries may be attributed to context-specific reasons. The findings in Singapore may be attributed partly to the consistent efforts of local and central government leaders to maintain regular contact with residents to convey relevant, accurate information on the latest pandemic insights and to debunk misinformation. Communication strategies for social distancing interventions, focusing on social responsibility (Tan and Chua 2022) further sought to align with the populations’ values (Yip et al. 2021). Thus, measures in Singapore were designed not only to be congruent with recommendations of recognized international health organizations or scientific evidence (Chua et al. 2020; Wong and Kohler 2020), but also with the country’s value system or social norms (Yip et al. 2021). Such efforts may have supported the pre-empting of policy shifts, and restored vertical trust in the legitimacy of national or local responses (Wong and Kohler 2020; Lim et al. 2021). In addition, respect for government leaders and regulations is high in Singapore (Chua et al. 2020), and residents hold expectations that the government will make decisive and adequate decisions to protect the citizens (Abdullah and Kim 2020). Thus, despite more stringent measures such as strict rules and tough penalties, a balance between legitimacy, authority, and trust could be maintained (Woo 2021), and hence may have preserved the social contract underlying the relationship between citizens and government. Taken together, these factors may have prevented a loss of vertical SC in Singapore during the pandemic.

In Switzerland, the federal government assigned a high degree of autonomy to cantonal leaders, allowing for responses tailored to specific local conditions (Pleninger et al. 2022). Communication of distancing measures largely focused on recommendations, and less on prohibitive mandates (Chen et al. 2021a; Pleninger et al. 2022). Such measures placed greater emphasis on more-persuasive instruments and voluntary compliance than on formal interdictions, which seem to be aligned with Switzerland’s value system and social contract (Sager and Mavrot 2020; Zimmermann et al. 2023). The stable vertical trust levels in both countries may further reflect beliefs in leaders to provide adequate protection, unbiased information, and scientific recommendations (SteelFisher et al. 2023). Thus, social distancing measures that were evidence-based (SteelFisher et al. 2023) and considered the respective countries’ value systems (Siegrist and Bearth 2021) or social contract framework conditions (Chin et al. 2023) may have supported the stability of vertical SC in a pandemic context.

Third, the results in this study point to higher horizontal and vertical SC levels among citizens with higher collectivistic orientation, compared with those with lower collectivistic orientation. This finding relates to studies suggesting that features underlying a higher collectivistic orientation, such as residents’ interdependencies (including shared goals) or in-group solidarity (including respect for authority) are linked to higher levels of horizontal trust (Shin and Park 2004; Pathak and Muralidharan 2016) and vertical trust (Jakubanecs et al. 2018; Leonhardt et al. 2020). Because higher trust levels reflect higher SC, higher collectivistic orientations that are expressed through shared goals, and support for and trust in each other, may result in higher levels of horizontal and vertical SC.

Furthermore, changes in SC were found to vary between groups with different levels of collectivistic orientation. In Singapore, individuals with lower collectivistic orientation had a significantly larger increase in vertical SC, compared with those with higher collectivistic orientation. However, a similar effect was not found in Switzerland, where changes in SC did not differ between groups with different levels of collectivistic orientation. It may be reasonable to speculate that in Singapore, the pandemic crisis and social distancing measures may have amplified or caused individuals with lower collectivistic orientation and possibly less community support to rely more on authorities for support and protection (Stevens and Haines 2020). This amplified reliance may have enhanced the exposure of individuals with low collectivistic orientation to government agencies or effective local services, thereby promoting a large and significant increase in vertical SC.

Our findings indicate that the links between collectivistic orientation and SC changes are multifaceted, differ by nations and contexts, and should be investigated in further detail. Modest differences in SC changes between age groups in Singapore, and in vertical SC changes between language groups in Switzerland, further suggest that changes in SC may depend on different sociodemographic characteristics across nations and contexts. The use of social archetypes to identify patterns of value configurations among residents in specific contexts may be explored to uncover further endogenous heterogeneity between population groups, even beyond single standard sociodemographic variables. Based on the respective insights, tailored interventions to cushion potential negative impacts of future social distancing measures on SC may be conceived.

There are limitations to this study. Changes in SC were assessed with repeated cross-sectional surveys during the pandemic (in June 2020 and July 2021) in Singapore and Switzerland. Thus, the findings are correlational. Reverse causation cannot be ruled out, and dynamic trends in SC within the study period cannot be captured. Longitudinal (panel) studies would be needed to confirm our results and to assess long-term trends in SC changes.

The use of online surveys may have introduced a sampling bias into the study. For example, it may be assumed that respondents with high digital literacy were overrepresented. However, this survey method offered efficient access and the possibility to collect demographically representative survey data on a national level. This was particularly valuable because our surveys were conducted in the pandemic context with social distancing measures in place. Hence, the use of other traditional survey methods was hardly feasible.

Furthermore, an evaluation of causal factors contributing to SC stability during pandemic contexts is needed. Although measures of SC in this study focused on the most widely cited indicators (Saja et al. 2018), we cannot exclude the possibility that other structural-level factors (e.g., the effectiveness of specific civic organizations, the existence of social welfare programs, or the economic framework conditions) may have influenced the stability of SC indicators. Future studies should analyze these factors to arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of changes in SC in the presence of social distancing rules.

Conclusion

The finding that horizontal and vertical SC remained stable in two different countries, in spite of the presence of social distancing rules, is encouraging, and potentially may suggest sustained social resilience during a pandemic. Evidence-based social distancing interventions tailored to the value system of a country and the innovative, adaptive capacities of citizens may have contributed to these positive results. Policymakers and relevant agencies working in social resilience potentially could benefit from increasing tailored communication and messaging efforts in future pandemic contexts. Further studies are warranted to determine the causal pathways responsible for retaining SC in pandemic settings.

Supplemental Materials

File (supplemental materials_nhrefo.nheng-2034_li.pdf)

- Download

- 257.28 KB

Data Availability Statement

All data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) program (Project No. 2019-N-162). All authors were involved in the production and writing of the manuscript. The authors thank the Home Team Behavioural Sciences Centre Singapore for their contributions to the study design, and Natalia Borzino and Ante Busic-Sontic, who contributed to the study design and data collection efforts.

References

Abdullah, W. J., and S. Kim. 2020. “Singapore’s responses to the COVID-19 outbreak: A critical assessment.” Am. Rev. Public Adm. 50 (6–7): 770–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020942454.

Aida, J., T. Hanibuchi, M. Nakade, H. Hirai, K. Osaka, and K. Kondo. 2009. “The different effects of vertical social capital and horizontal social capital on dental status: A multilevel analysis.” Soc. Sci. Med. 69 (4): 512–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.003.

Aldrich, D. 2010. “Fixing recovery: Social capital in post-crisis resilience.” J. Homel. Secur. 6 (May): 1–10.

Aldrich, D. P., and M. A. Meyer. 2015. “Social capital and community resilience.” Am. Behav. Sci. 59 (2): 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214550299.

Barrios, J. M., E. Benmelech, Y. V. Hochberg, P. Sapienza, and L. Zingales. 2021. “Civic capital and social distancing during the Covid-19 pandemic.” J. Public Econ. 193 (Jan): 104310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104310.

Bartscher, A. K., S. Seitz, S. Siegloch, M. Slotwinski, and N. Wehrhöfer. 2021. “Social capital and the spread of covid-19: Insights from European countries.” J. Health Econ. 80 (Dec): 102531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102531.

Beilmann, M., and A. Realo. 2012. “Individualism–collectivism and social capital at the individual level.” Trames. J. Humanit. Soc. 16 (Apr): 205. https://doi.org10.3176/tr.2012.3.01.

Bhandari, H., and K. Yasunobu. 2009. “What is social capital? A comprehensive review of the concept.” Asian J. Soc. Sci. 37 (3): 480–510. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853109X436847.

Biddlestone, M., R. Green, and K. M. Douglas. 2020. “Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19.” Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 59 (3): 663–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12397.

Borkowska, M., and J. Laurence. 2021. “Coming together or coming apart? Changes in social cohesion during the Covid-19 pandemic in England.” Eur. Soc. 23 (1): 618–636. https://doi.org10.1080/14616696.2020.1833067.

Bourdieu, P. 1986. The forms of capital: Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education, 241–258. New York: Greenwood Press.

Busic, A., and R. Schubert. 2022. “Social resilience indicators for pandemic crises.” Disasters 48 (2): e12610. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12610.

Chen, D., D. Peng, M. O. Rieger, and M. Wang. 2021a. “Institutional and cultural determinants of speed of government responses during COVID-19 pandemic.” Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8 (1): 171. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00844-4.

Chen, E., P. H. Lam, E. D. Finegood, N. A. Turiano, D. K. Mroczek, and G. E. Miller. 2021b. “The balance of giving versus receiving social support and all-cause mortality in a US national sample.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118 (24): e2024770118. https://doi.org10.1073/pnas.2024770118.

Chin, I., J. Joerin, and R. Schubert. 2023. “Strengthening social resilience—The importance of trust.” Accessed August 3, 2023. https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/dual/frs-dam/documents/FRS_Working_Paper_7_Strengthening%20Social%20Resilience.pdf.

Chua, A. Q., M. M. J. Tan, M. Verma, E. K. L. Han, L. Y. Hsu, A. R. Cook, and H. Legido-Quigley. 2020. “Health system resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from Singapore.” BMJ Glob. Health 5 (9): e003317. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003317.

Comstock, N., L. M. Dickinson, J. A. Marshall, M. J. Soobader, M. S. Turbin, M. Buchenau, and J. S. Litt. 2010. “Neighborhood attachment and its correlates: Exploring neighborhood conditions, collective efficacy, and gardening.” J. Environ. Psychol. 30 (4): 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.05.001.

De Jesus, M., B. Warnock, Z. Moumni, Z. H. Sougui, and L. Pourtau. 2023. “The impact of social capital and social environmental factors on mental health and flourishing: The experiences of asylum-seekers in France.” Confl. Health 17 (1): 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-023-00517-w.

Department of Statistics Singapore. 2021. “Population trends 2021.” Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/population/population2021.pdf.

Federal Council. 2020. “Coronavirus: Verstärkter Schutz besonders gefährdeter Personen und Evaluation der wirtschaftlichen Auswirkungen.” Accessed May 7, 2023. https://www.admin.ch/gov/de/start/dokumentation/medienmitteilungen.msg-id-78381.html.

Federal Statistical Office. 2017. “Statistical Data on Switzerland 2017.” Accessed May 12, 2023. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/en/home/statistics/catalogues-databases/publications/overviews/statistical-data-switzerland.assetdetail.2040009.html.

Federal Statistical Office. 2022. “Demographic portrait of Switzerland.” Accessed May 23, 2023. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/asset/fr/480-2000.

Fraser, T., and D. P. Aldrich. 2021. “The dual effect of social ties on COVID-19 spread in Japan.” Sci. Rep. 11 (1): 1596. https://doi.org10.1038/s41598-021-81001-4.

Guo, Y., and J. Woo. 2016. Singapore and Switzerland: Secrets to small state success. Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific Publishing.

Jakubanecs, A., M. Supphellen, and J. G. Helgeson. 2018. “Crisis management across borders: Effects of a crisis event on consumer responses and communication strategies in Norway and Russia.” J. East-West Bus. 24 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669868.2017.1381214.

Jennings, V., and O. Bamkole. 2019. “The relationship between social cohesion and urban green space: An avenue for health promotion.” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16 (3): 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16030452.

Kwok, A. H., E. E. Doyle, J. Becker, D. Johnston, and D. Paton. 2016. “What is ‘social resilience’? Perspectives of disaster researchers, emergency management practitioners, and policymakers in New Zealand.” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 19 (Jun): 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.08.013.

Layla, K., R. Schubert, and J. Joerin. 2020. “Social resilience indicators for disaster-related contexts: Literature review.” Accessed June 1, 2023. https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/dual/frs-dam/documents/Social%20resilience_Working%20paper_final%20(Jul-25-2020).pdf.

Leonhardt, J. M., T. Pezzuti, and J. E. Namkoong. 2020. “We’re not so different: Collectivism increases perceived homophily, trust, and seeking user-generated product information.” J. Bus. Res. 112 (May): 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.017.

Lim, V. W., R. L. Lim, Y. R. Tan, A. S. Soh, M. X. Tan, N. B. Othman, and M. I. Chen. 2021. “Government trust, perceptions of COVID-19 and behaviour change: Cohort surveys, Singapore.” Bull. World Health Organ. 99 (2): 92–101. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.269142.

Lindström, M., and G. N. Giordano. 2016. “The 2008 financial crisis: Changes in social capital and its association with psychological wellbeing in the United Kingdom—A panel study.” Soc. Sci. Med. 153 (Mar): 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.008.

Onyeaka, H., C. K. Anumudu, Z. T. Al-Sharify, E. Egele-Godswill, and P. Mbaegbu. 2021. “COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects.” Sci. Prog. 104 (2): 003685042110198. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504211019854.

Page-Tan, C. 2021. “Bonding, bridging, and linking social capital and social media use: How hyperlocal social media platforms serve as a conduit to access and activate bridging and linking ties in a time of crisis.” Nat. Hazards 105 (2): 2219–2240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04397-8.

Pathak, S., and E. Muralidharan. 2016. “Informal institutions and their comparative influences on social and commercial entrepreneurship: The role of in-group collectivism and interpersonal trust.” J. Small Bus. 54 (1): 168–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12289.

Pitas, N., and C. Ehmer. 2020. “Social capital in the response to COVID-19.” Am. J. Health Promot. 34 (8): 942–944. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120924531.

Pleninger, R., S. Streicher, and J. E. Sturm. 2022. “Do COVID-19 containment measures work? Evidence from Switzerland.” Swiss J. Econ. Stat. 158 (1): 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-022-00083-7.

Prime Minister’s Office (Singapore). 2023. “White paper on Singapore’s response to COVID-19: Lessons for the next pandemic.” Accessed May 21, 2023. https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/government_records/docs/f3964eb4-c865-11ed-a758-0050569c7836/Cmd.22of2023.pdf?.

Realo, A., and J. Allik. 2009. “On the relationship between social capital and individualism–collectivism.” Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 3 (6): 871–886. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00226.x.

Realo, A., J. Allik, and M. Vadi. 1997. “The hierarchical structure of collectivism.” J. Res. Pers. 31 (1): 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2170.

Sager, F., and C. Mavrot. 2020. “Switzerland’s COVID-19 policy response: Consociational crisis management and neo-corporatist reopening.” Eur. Policy Anal. 6 (2): 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1094.

Saja, A. M. A., M. Teo, A. Goonetilleke, and A. M. Ziyath. 2018. “An inclusive and adaptive framework for measuring social resilience to disasters.” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 28 (Jun): 862–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.02.004.

Samutachak, B., K. Ford, V. Tangcharoensathien, and K. Satararuji. 2023. “Role of social capital in response to and recovery from the first wave of COVID-19 in Thailand: A qualitative study.” BMJ Open 13 (1): e061647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061647.

Saraniemi, S., T. Harrikari, V. Fiorentino, M. Romakkaniemi, and L. Tiitinen. 2022. “Silenced coffee rooms—The changes in social capital within social workers work Communities during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.” 13 (1): 8. https://doi.org10.3390/challe13010008.

Sato, K., N. Kondo, and K. Kondo. 2022. “Pre-pandemic individual- and community-level social capital and depressive symptoms during COVID-19: A longitudinal study of Japanese older adults in 2019-21.” Health Place 74 (Jun): 102772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2022.102772.

Sharifian, N., J. J. Manly, A. M. Brickman, and L. B. Zahodne. 2019. “Social network characteristics and cognitive functioning in ethnically diverse older adults: The role of network size and composition.” Neuropsychology 33 (7): 956–963. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000564.

Shekriladze, I., N. Javakhishvili, and N. Chkhaidze. 2021. “Culture related factors may shape coping during pandemics.” Front. Psychol. 12 (Apr): 634078. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.634078.

Shin, H. H., and T. H. Park. 2004. “Individualism, collectivism and trust: The correlates between trust and cultural value orientations among Australian national public officers.” Int. J. Public Adm. 9 (2): 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2005.10805053.

Siegrist, M., and A. Bearth. 2021. “Worldviews, trust, and risk perceptions shape public acceptance of COVID-19 public health measures.” PNAS 118 (24): e2100411118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2100411118.

SteelFisher, G. K., M. G. Findling, H. L. Caporello, K. M. Lubell, K. G. Vidoloff Melville, L. Lane, and E. N. Ben-Porath. 2023. “Trust in US federal, state, and local public health agencies during COVID-19: Responses and policy implications.” Health Aff. 42 (3): 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01204.

Stevens, H., and M. B. Haines. 2020. “TraceTogether: Pandemic response, democracy, and technology.” East Asian Sci. Technol. Soc. 14 (3): 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1215/18752160-8698301.

Sun, K. S., T. S. M. Lau, E. K. Yeoh, V. C. H. Chung, Y. S. Leung, C. H. K. Yam, and C. T. Hung. 2022. “Effectiveness of different types and levels of social distancing measures: A scoping review of global evidence from earlier stage of COVID-19 pandemic.” BMJ Open 12 (4): e053938. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053938.

Szreter, S., and M. Woolcock. 2004. “Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health.” Int. J. Epidemiol. 33 (4): 650–667. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh013.

Tan, O. S., and J. J. E. Chua. 2022. “Science, social responsibility, and education: The experience of Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Accessed April 1, 2023. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/50965/1/978-3-030-81500-4.pdf#page=261.

Tatarko, A., T. Jurcik, and K. Boehnke. 2022. “Social capital and the COVID-19 pandemic threat: The Russian experience.” Front. Sociol. 7 (Dec): 957215. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2022.957215.

Triandis, H. 2019. Individualism and collectivism. New York: Routledge.

Wong, A. S. Y., and J. C. Kohler. 2020. “Social capital and public health: Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.” Global Health 16 (1): 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00615-x.

Woo, J. J. 2021. “Pandemic, politics and pandemonium: Political capacity and Singapore’s response to the COVID-19 crisis.” Policy Des. Pract. 4 (1): 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1835212.

Yip, W., L. Ge, A. H. Y. Ho, B. H. Heng, and W. S. Tan. 2021. “Building community resilience beyond COVID-19: The Singapore way.” Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 7 (Jun): 100091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100091.

Yu, B., M. Luo, M. Liu, J. Zhou, S. Yang, and P. Jia. 2021. “Social capital changes after COVID-19 lockdown among youths in China: COVID-19 impact on lifestyle change survey (COINLICS).” Front. Public Health 9 (5): 697068. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.697068.

Zimmermann, B. M., A. Buyx, and S. McLennan. 2023. “Newspaper coverage on solidarity and personal responsibility in the COVID-19 pandemic: A content analysis from Germany and German-speaking Switzerland.” SSM Popul. Health 22 (Jun): 101388. https://doi.org10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101388.

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Copyright

This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

History

Received: Sep 21, 2023

Accepted: May 2, 2024

Published online: Jul 8, 2024

Published in print: Nov 1, 2024

Discussion open until: Dec 8, 2024

ASCE Technical Topics:

- Asset management

- Bodies of water (by type)

- Business management

- Channels (waterway)

- Coasts, oceans, ports, and waterways engineering

- Decision making

- Diseases

- Distance measurement

- Engineering fundamentals

- Epidemic and pandemic

- Financial management

- Health hazards

- Hydraulic engineering

- Hydraulic structures

- Measurement (by type)

- Practice and Profession

- Public administration

- Public health and safety

- River engineering

- Social factors

- Structural engineering

- Structures (by type)

- Water and water resources

- Water management

- Waterways

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Download citation

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.