Interplay of Industrial Transformation, Diversified Governance, and Talent Gathering on the Ruralization of China

Publication: Journal of Urban Planning and Development

Volume 151, Issue 1

Abstract

This paper examines the evolution from urbanization to ruralization in China, highlighting the role of national strategies in promoting the coordinated development of urban and rural areas. By introducing the concept of ruralization as part of China's rural revitalization, which aims for sustainable development through a balance of top-down and endogenous forces, this study first asserts that ruralization is a rural development process initiated by rural revitalization once urbanization reaches a certain threshold and is sustained by both rural revitalization and urbanization. Then, using the Yuhang District in Zhejiang as the case, this paper discusses an interplay mechanism formed by three key drivers of ruralization, namely, industrial transformation, diversified governance, and talent gathering. Additionally, when applied to mountainous regions like Anji and Yunhe in Zhejiang, the Yuhang case serves as an adaptable model to suit local ecological and social-economic contexts. This paper concludes with recommendations for maintaining the pros of Yuhang's ruralization and offering insights into other regions.

Introduction

Since China's reform and opening up, urbanization has emerged as a pivotal theme, marked by rapid progress. However, the longstanding urban–rural dual structure has not only increased urban and rural disparity along with exacerbated urban issues but also resulted in the deterioration of the rural system with such problems as hollowing out, aging populations, landscape fragmentation, and inadequate protection of nature and cultural heritage (Aksoy et al. 2022). The officially promoted concepts of smart cities and global cities use the rationality of technological management to obscure the reality that projects such as Dholera special investment region and Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor view the land of marginal villages as a resource available for development. These concepts ignore the rural population and their lived realities and treat the existing marginality as a foundation to be utilized rather than a social problem that needs to be addressed (Datta 2015; Ghosh, n.d.). In response, China has launched a rural revitalization strategy to foster urban–rural integration and mutual prosperity. This new official narrative and planning reflects a hybrid nature-culture perspective, one that neither separates the protection of nature from human intervention nor embraces a deterministic view of nature's dominance over human society (Chen and Kong 2022).

This paper argues that urbanization and rural revitalization should not be considered in isolation. Instead, they should be integrated based on the human–land territorial system, providing a new framework for understanding modern urban–rural relations and addressing rural development challenges (Chen et al. 2021). Recent scholarship increasingly adopts a relational perspective, focusing on rural–urban interactions rather than solely urban-centric views (Geng and Maimaituerxun 2022; Ghosh 2022; Woods 2007). The fluid two-way flow of factors between urban and rural areas has brought them closer, with industrial transformation, governance innovation, and talent migration to rural areas serving as key drivers of this interaction. This study introduces a theoretical model of ruralization, analyzing its evolution through literature review, statistical, and regression analysis, alongside a case study of the Yuhang District in Zhejiang. This district exemplifies the collaborative model between mountainous and urban areas under the dual strategies of urbanization and rural revitalization. The paper explores the synergistic mechanisms of industrial transformation, diversified governance, and talent gathering, aiming to offer insights into similar developmental contexts.

Literature Review

In the academic context, where many studies have reduced the rural to an obsolescent category (a historical starting point) or a residual space (an unconsumed world), scholars like Jamie Gillen have provided clear definitions of the concept and pathways of ruralization. They focused their attention on ruralization because they believed it could serve to reveal those elements of the rural that are persistent, resonant, and pervasive even in an urbanizing world (Gillen et al. 2022). Similarly, in Roy’s reading, the rural does not simply constitute the not-urban but is a constitutive outside of the urban that is in constant negotiation with the processes of urbanization in the Global South (Roy 2016). Gillen argued in favor of rural–urban interactions rather than urban-centric sociospatial transformations. Based on research on human spatial practices, identities, and aspirations in Southeast Asia, he outlined three main components of ruralization. The first is in situ ruralization, which refers to the rural dynamics related to the spatial reproduction of small farmers. The second is extended ruralization, which remains a component of urban and suburban life. The third is the rural reward, which is the cross-regional arrangement between rural and urban areas. For many people, the urban area is primarily a place for earning money, launching a career, providing better educational opportunities for their children, and enjoying some of the modern conveniences of urban life (Gillen et al. 2022; Hansen 2018). However, the urban area is not home, leading to a need and even a requirement for appropriate feedback to the countryside. While urban area dwellers may not be able to physically live in the countryside, there can be different forms of rewards including endowments, banquets, charitable donations, pagoda refurbishment, and construction of second homes in the countryside, and so on. Ghosh, based on an analysis of Gillen's concept of ruralization, has described ruralization as the sustained survival of rural families under a continuous upgrading of deruralization (Araghi 2012; Ghosh, n.d.; Li 2010). He defined extended ruralization as the driving force behind it and believed that ruralization refers to the transformation of urban and periurban areas driven by “rural change and social action by rural people.” In various regions of rural China, numerous on-site experiments focusing on green development have been conducted, drawing attention to ruralization imperatives, uses of the past, and harmonious human–nature relations during the ruralizing process (Chen and Kong 2022).

McGee’s discussions on rural development, based on observations of lifestyle and landscape changes in Indonesia, not only transcended the binary assumption of rural versus urban but also laid the foundation for conceptualizing the ongoing dynamics of ruralization (McGee 2002; McGee 2013; Richardson 2017). This helps us understand why rural people, rural activities, and rural sentiments still exist against the backdrop of thorough urbanization, a motivation that is shared in the context of urbanization everywhere today. Scholars are more mature in studying rural revitalization, rural development networks, functional diversification of rural development, and other models of rural development (Botes and Van Rensburg 2000; Chambers 1994; Marsden 2010; Murdoch 2000; Olfert and Partridge 2010; Ryser and Halseth 2010). For example, researchers conducted a study on the five revitalizations of rural revitalization. Research proposed four major paths to reference China's rural revitalization by re-examining the typical facts of rural transformation in East Asia. In addition, a large number of scholars have proposed countermeasures for rural industrial revitalization from the perspectives of urban–rural integration and development, from efficiency to fairness, the relationship between the elements of the rural production spatial system, and industrial integration. Currently, scholars have focused a large amount of research on exploring modes and paths of rural revitalization; such articles are at the beginning of the study of ruralization, but most of them are in the exploratory stage. To understand the trajectory of urbanization that is different from the European and American experience, we must step out of the standard framework of urban theory and seek a new analytical framework. To this end, scholars have attempted to reconcile urban studies and agricultural studies and to propose a development process in which the dynamics of agriculture and the city mutually support and generate each other without erasing or assimilating the rural (Gururani 2020).

In the process of rural development, on the one hand, industrial transformation plays a significant role. Scholars studying the suburbs of major Chinese cities have found that the tradeoff between residential and industrial functions (especially nonagricultural production functions) in rural areas may have some adverse ecological impacts initially. However, these impacts are temporary, and in the long run, this tradeoff seems beneficial for improving ecological quality. Consequently, rural development can promote sustainable planning in villages by effectively strategizing to coordinate livable residential housing, efficient industrial production, and eco-friendly management (Ma et al. 2018). From a long-term perspective, this article supports the critical role of rural industrial transformation in the sustainable development of rural areas. On the other hand, in the process of rural development, the aggregation of rural talent and diversified governance contribute significantly to the self-sufficiency of rural communities and the achievement of a better future. For instance, in the context of the profound impact of industrialized agriculture on rural communities, Amish effectively address the brain drain by creating industries centered around human capital, such as construction and cabinetry, and by establishing cooperative community networks. They enhance community self-sufficiency by setting up insurance funds, providing financial assistance, and optimizing distribution systems. Moreover, through a comprehensive apprenticeship system that trains skilled artisans, they emphasize the value of manual labor and encourage members to remain within the community (Mathias et al. 2024). Previous studies have examined the role and efficacy of ruralization (Bakari and El Weriemmi 2022; Baron et al. 2019); however, they are insufficient for developing a fully inclusive analysis of ruralization and rural–urban relations. In general, not many studies have been conducted on the interaction between urbanization and ruralization with Chinese characteristics and the mechanisms behind ruralization.

Theoretical Framework

From Urbanization to Rural Revitalization

From 1940 to 1980, the dual-structure paradigm was prevalent in the study of urban–rural relations in the West, primarily focusing on urban and industrial growth, which often overshadowed rural agricultural development (Lewis 2013). In China, since the 1950s, the emphasis on industrial prioritization and urban-centric policies has exacerbated the urban–rural divide, intensifying segregation and solidifying the dual structure (Chen et al. 2021). Urbanization, characterized by the expansion of urban areas and population and the dissemination of urban values and behaviors, has reshaped rural landscapes (Bakari and El Weriemmi 2022). Postreform and opening up, urbanization accelerated rapidly in China, achieving in about 40 years what took some Western nations nearly a century, but also leading to issues such as urban–rural inequality, brain drain, and village decline (Chen and Kong 2022). For many, including migrant workers and urban dwellers, the urban environment represents a harsh reality, whereas the countryside remains an ideal (Parsons and Lawreniuk 2022). In response to these challenges, China introduced the National Rural Revitalization Strategy in 2017, aiming to address these critical rural issues.

From Rural Revitalization to Ruralization

As urbanization and industrialization progress, they bring about ecological and social shifts that enhance the perceived economic, social, cultural, and ecological values of rural areas. These changes have sparked a renewed interest in rural lifestyles among urban dwellers, leading to a trend of counter-urbanization where urban residents move back to rural areas, offering both new opportunities and challenges for rural development (Li et al. 2012). This phenomenon indicates that urbanization and modernization are not merely linear or unidirectional processes but involve a complex interplay and integration of urban and rural dynamics, tradition, and modernity. In response, China has merged the strategies of new urbanization and rural revitalization (Abdul-Wakeel Karakara and Dasmani 2019), aiming to foster integrated and coordinated development between urban and rural areas (Lankoski and Thiem 2020). Significant investments in rural infrastructure and the ecological environment under the rural revitalization strategy have not only strengthened the foundation for ruralization but have also accelerated its progression.

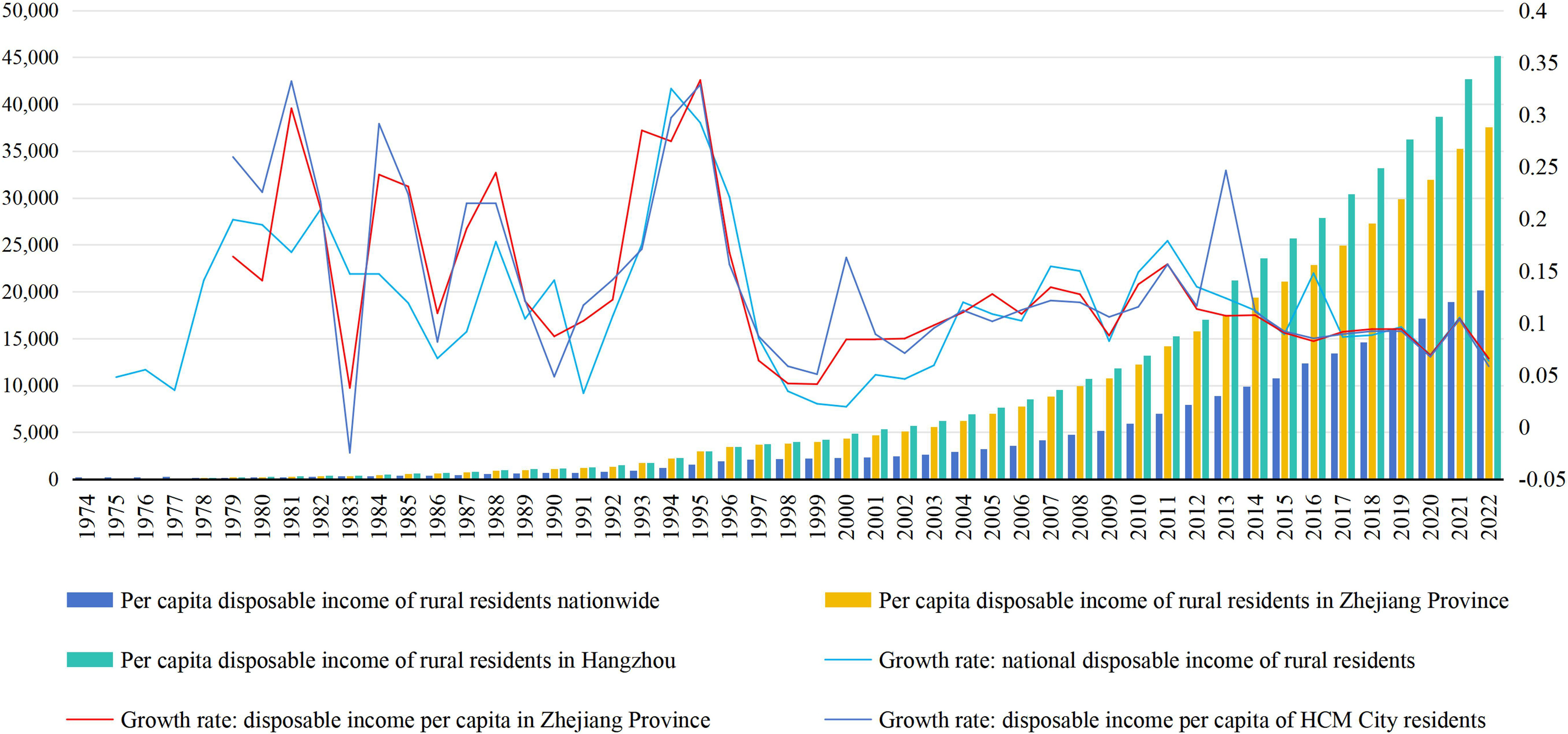

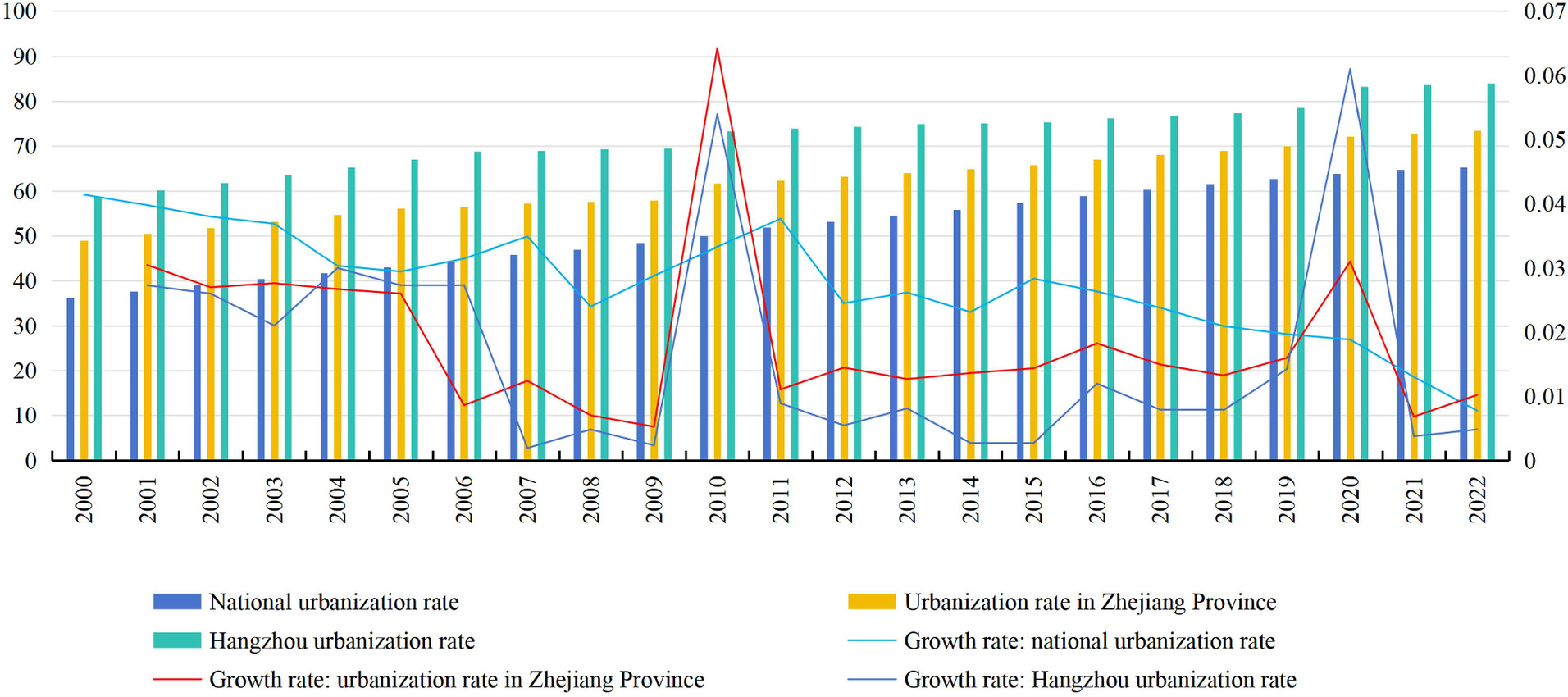

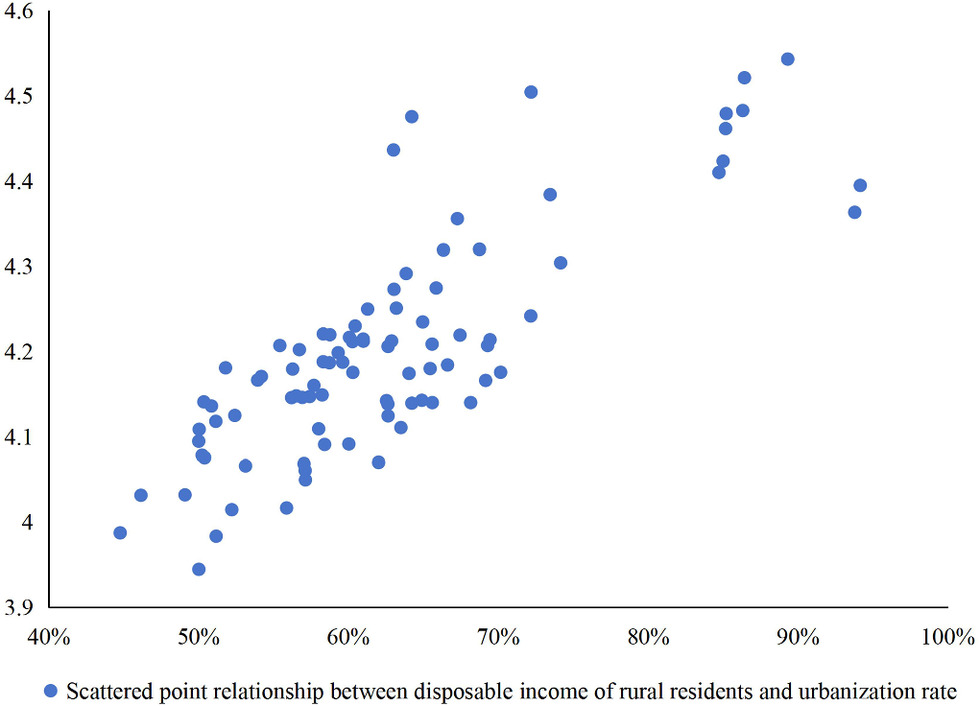

Statistical analysis of the historical data on per capita disposable income of rural residents from 1974 to 2022 (Fig. 1) and urbanization rates from 2000 to 2022 (Fig. 2) across the national, Zhejiang Province, and Hangzhou urban area levels reveals a positive correlation between urbanization and rural income levels. For instance, regions with higher urbanization rates, like Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin, exhibit higher rural incomes compared to less urbanized provinces such as Yunnan, Gansu, and Guizhou. This relationship is depicted in a scatter plot (Fig. 3), showing a general upward trend to the upper right, suggesting a linear relationship between urbanization levels and rural incomes across China's 30 provinces (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, and Tibet). This analysis confirms that urbanization positively influences rural income levels, supporting the interconnected growth of urbanization and ruralization.

Using data from 30 Chinese provinces (2015–2022), an ordinary least-squares (OLS) regression analysis was conducted to assess the impact of urbanization on rural per capita disposable income. Initially, with only the urbanization rate as the variable, the coefficient was significant at the 1% level, showing that a 1% increase in urbanization correlates with a 20.3% rise in rural income. When incorporating additional variables like GDP, education, population aging, and agricultural output, the coefficient reduced to 0.166, still significant at the 5% level, indicating a 16.6% increase in rural income per percent increase in urbanization (Table 1). These results confirm that urbanization is a significant driver of rural economic enhancement, illustrating the parallel progress of ruralization and urbanization in China’s socioeconomic landscape.

| Variables and parameters | Univariate | Multivariate |

|---|---|---|

| Urbanization rate | 0.203*** (0.072) | 0.166** (0.067) |

| GDP | — | 0.021*** (0.000) |

| Educational level | — | 0.671 (2.409) |

| Population aging | — | −0.512 (0.309) |

| Total output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery | — | 0.033*** (0.000) |

| _cons | 9.574*** (0.039) | 9.574*** (0.051) |

| N | 240 | 240 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.998 | 0.998 |

**Indicates statistical significance at the 0.01 level (p < 0.01); and ***indicates statistical significance at the 0.001 level (p < 0.001).

Model of Interplays of Industrial Transformation, Diversified Governance, and Talent Gathering on Ruralization

Building on prior research and Adam Smith's perspective that rural areas should precede urban development (Geng and Maimaituerxun 2022), this paper proposes a sequential development model where urbanization leads to ruralization. Drawing on the coexistence of traditional elements in rural areas and modern aspects in urban settings (Lin et al. 2016), ruralization is conceptualized as a development process originating in rural areas. This process is catalyzed by rural revitalization after urbanization reaches a certain threshold and is continuously driven by both rural revitalization and urbanization.

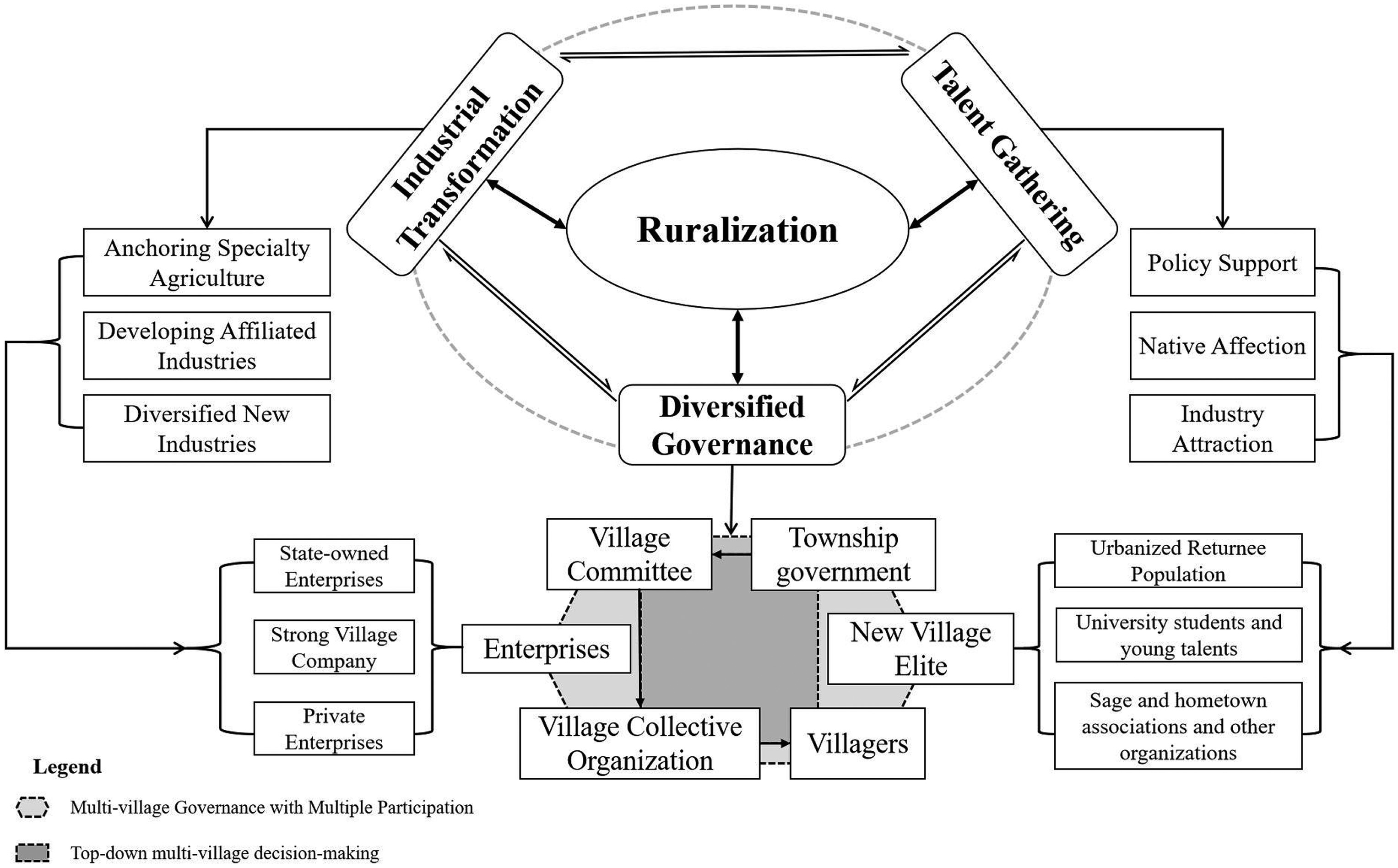

Central to this rural–urban interaction are the dynamics of industrial transformation, governance innovation, and the migration of talent to rural areas. The ruralization model proposed here (Fig. 4) is characterized by the return of urbanized populations to well-connected rural areas, leveraging physical space for self-sustaining development. This model integrates both bottom-up and top-down approaches, differing fundamentally from the top-down strategy of rural revitalization, and embodies a self-supporting rural development process in the posturbanization period.

Materials and Methods

Study Area and Ruralization in Yuhang District, Zhejiang

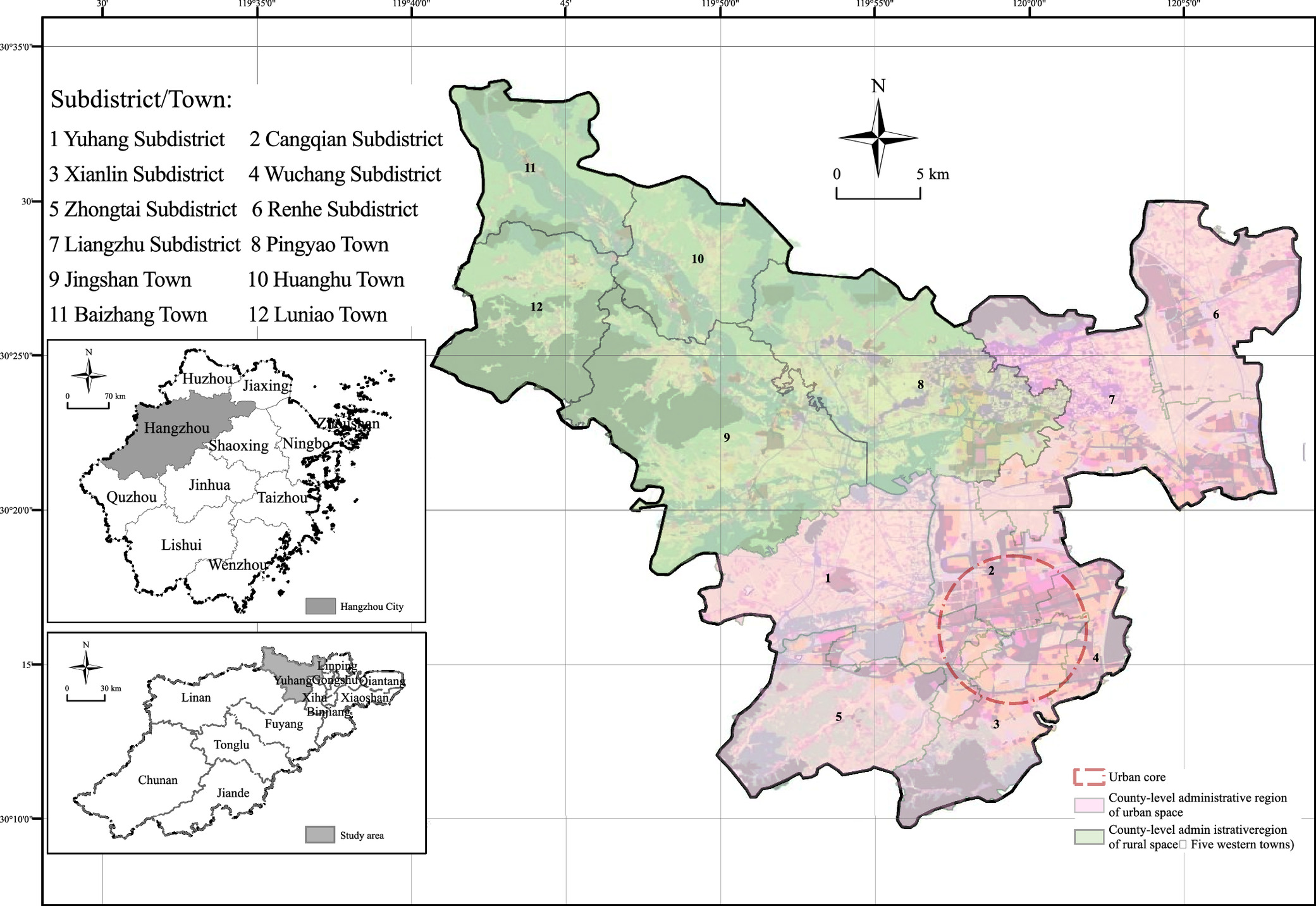

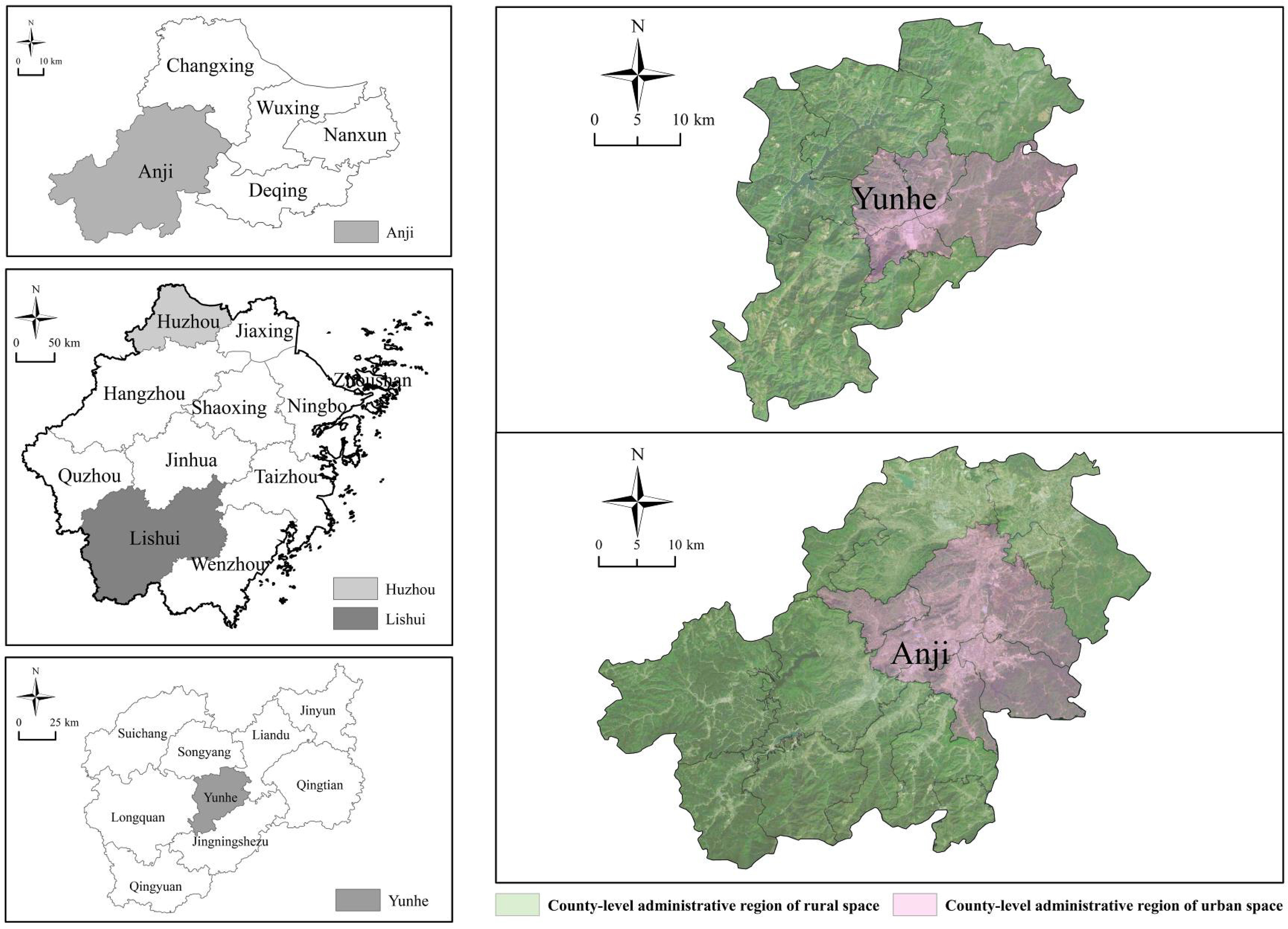

In China, urbanization and rural revitalization strategies must adapt to diverse geographic types and developmental stages. Zhejiang Province, characterized by its “seven mountains, one water, two fields” topography, distinguishes between more urbanized cities and less developed mountainous regions among its 26 counties. Yuhang District has emerged as a provincial leader by exemplifying “Mountainous-Urban area Collaboration” within the National Common Wealth Demonstration Zone strategy (Fig. 5). This model promotes economic integration and mutual growth between urban and mountainous areas, serving as a benchmark for balanced regional development across Zhejiang.

Fig. 5. (Color) Sketch map of the study area.

[Base map by the Standard Map Service system of the China Ministry of Natural Resources, No. GS (2023)2767.]

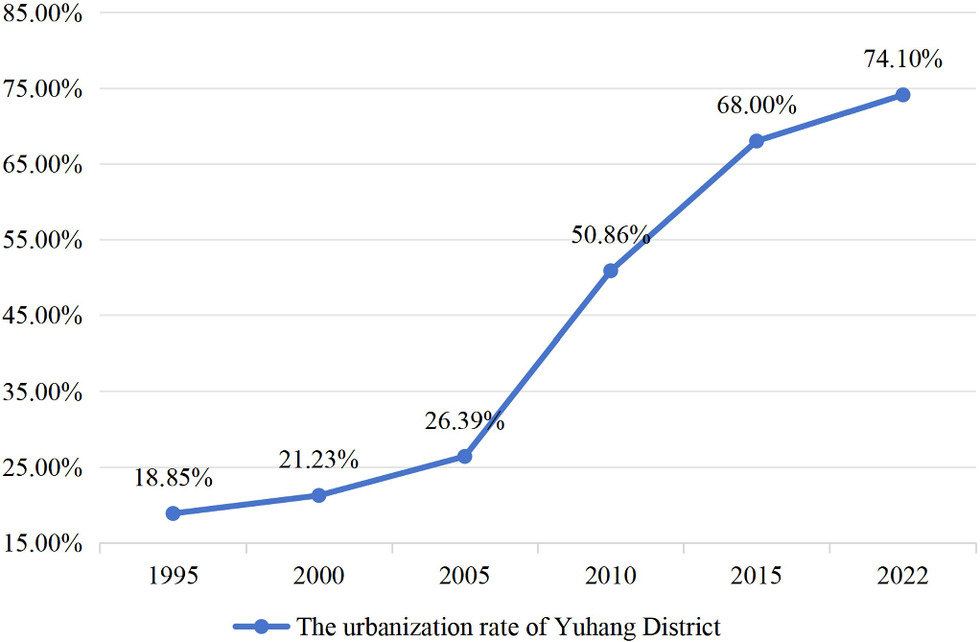

In 2022, Yuhang District in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, led the region with a GDP of 265.125 billion yuan, largely driven by its digital economy, which constitutes 64.1% of its GDP. The district has experienced significant urbanization since 1995, notably peaking in 2015 (Fig. 6). Yuhang is pivotal in Hangzhou’s innovation landscape, hosting the Future Science and Technology City across five subdistricts: Cangqian, Wuchang, Yuhang, Xianlin, and Zhongtai. Yuhang Subdistrict is one of the subdistricts under the jurisdiction of Yuhang District. This hub focuses on digital economy and biomedicine, featuring major firms like Alibaba and OPPO, and acts as the city's third center for industrial advancement. Geographically, Yuhang spans from the Hangzhou–Jiaxing–Huzhou Plain to the hilly western Zhejiang, forming a diverse landscape with five mountainous towns: Pingyao, Jingshan, Huanghu, Luniao, and Baizhang.

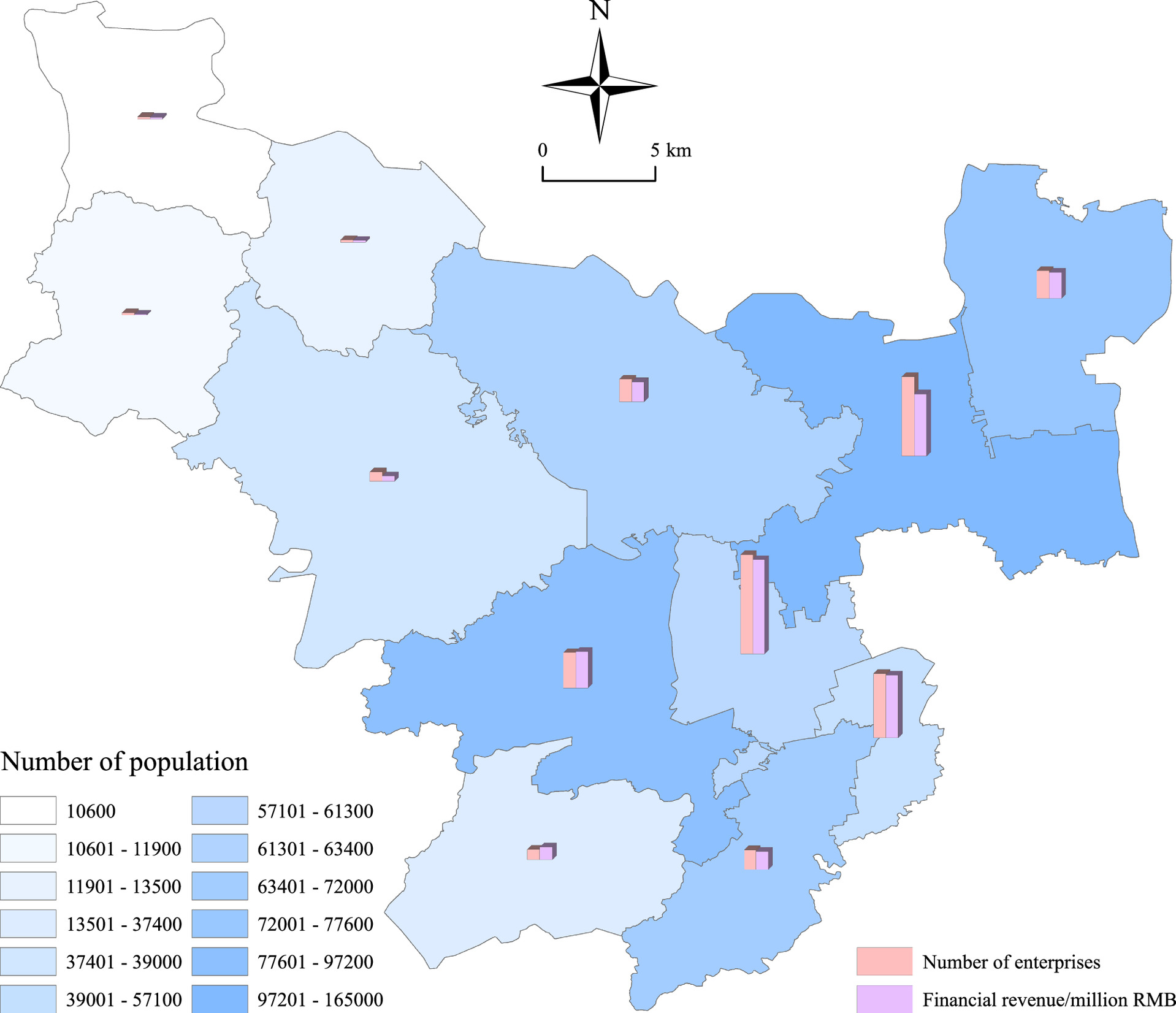

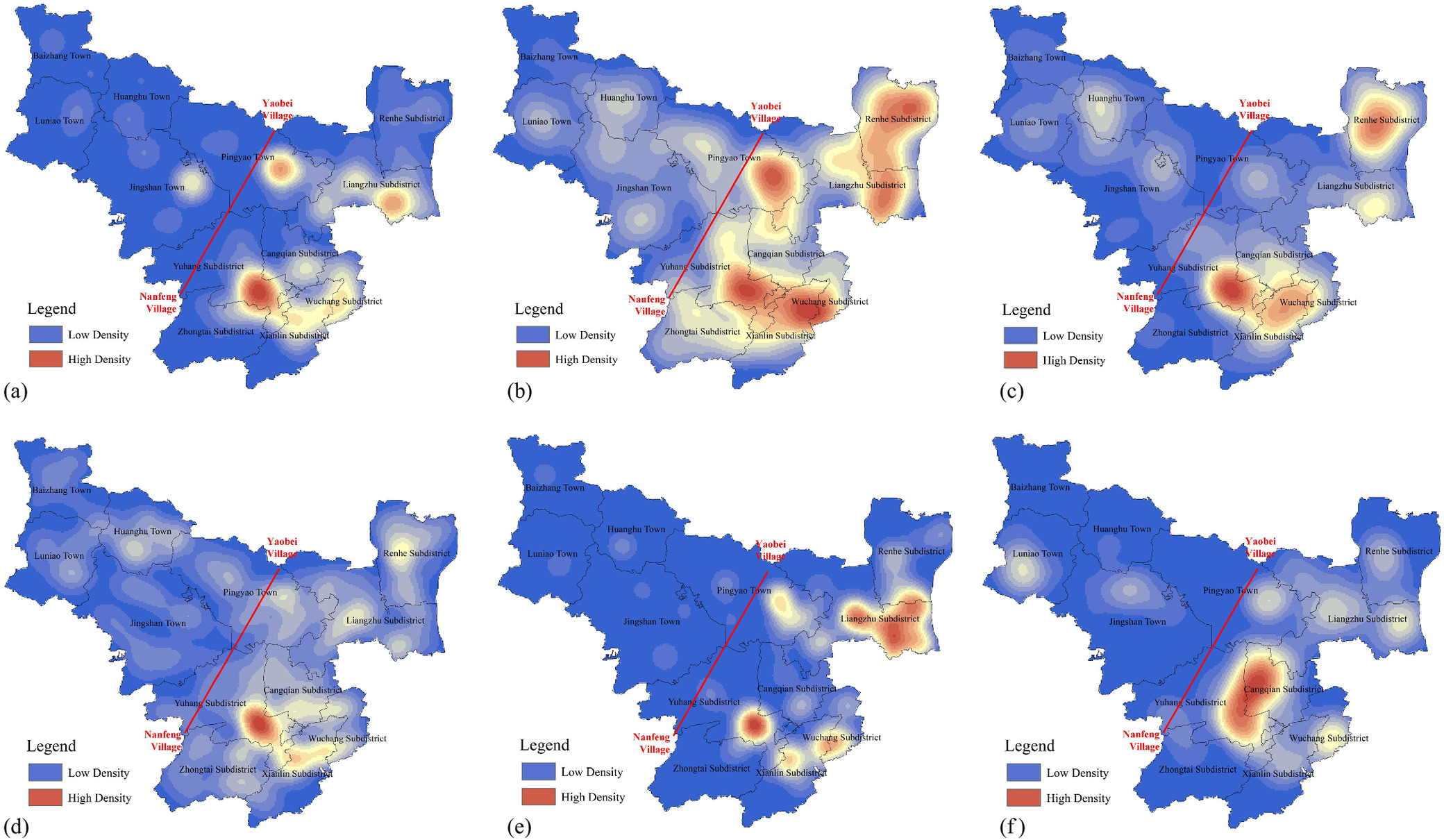

There are disparities in the development of Yuhang District between Mountainous area and Urban area. First, the Mountainous area lacks industry, the five towns in the west of Yuhang District have weak industry, and the number of enterprises in the five towns in the west only accounts for 10.3% of the whole area (Table 2 and Fig. 7). Second, the talent is reluctant to come; according to the seventh census data, the western five towns accounted for 16.3% of the population of the region; specifically, Huanghu Town, Luniao Town, and Baizhang Town accounted for a total of only 2.8% of the total population. Compared to the sixth national census, the areas with significant growth in the past decade are mainly located in the main urban areas (Fig. 7). Third, the service is fault-lined. There is a spatial fault in the distribution of public service facilities in the region, leading to the formation of a geographic division line (Nanfeng Village–Taobei Village Line); in the western region, there is a large gap in the education services, medical services, elderly services, public station facilities, supermarket services, leisure and recreational facilities compared to the main urban areas (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7. (Color) Distribution of enterprises, fiscal revenue, and population in Yuhang District.

[Base map by the Standard Map Service system of the China Ministry of Natural Resources, No. GS (2023)2767; (Data from Yuhang District Government 2022.)

Fig. 8. (Color) Distribution of public service facilities in Yuhang District: (a) density of educational service facilities distribution; (b) density of medical service facilities distribution; (c) density of elderly service facility distribution; (d) density of bus stop distribution; (e) density of commercial and supermarket service facility distribution; and (f) density of leisure and entertainment service facility distribution.

(Map data from Tianditu, https://www tianditu.gov.cn.)

| Subdistrict | Number of enterprises | Percentage share of total number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Cangqian Subdistrict | 24,529 | 26.57 |

| Liangzhu Subdistrict | 19,548 | 21.17 |

| Wuchang Subdistrict | 15,818 | 17.13 |

| Yuhang Subdistrict | 8,706 | 9.43 |

| Renhe Subdistrict | 6,889 | 7.46 |

| Xianlin Subdistrict | 4,833 | 5.24 |

| Zhongtai Subdistrict | 2,487 | 2.69 |

| Pingyao Town | 5,471 | 5.93 |

| Jingshan Town | 2,274 | 2.46 |

| Huanghu Town | 618 | 0.67 |

| Luniao Town | 583 | 0.63 |

| Baizhang Town | 563 | 0.61 |

| Five western towns | 9,509 | 10.30 |

| (Grand) total | 92,319 | 100.00 |

Note: Data from Yuhang District Government (2022).

Methods

This paper drew on the analytical methods of the feedback mechanisms among population, land, and industry from the Shandong rural transformation study to conduct an empirical analysis of the “Industrial Transformation–Diversified Governance–Talent Gathering” mechanism in the ruralization process of Yuhang District. Through a combination of theoretical analyses and empirical methods, the research analyzed the rural transformation development in Shandong Province, focusing on the interactions among population, land, and industry. It also proposed region-specific optimization strategies to address observed disparities and imperfections for sustainable development (Hu et al. 2016; Tingting and Hualou 2015). The research methods used in this study are as follows.

Statistical Analysis

This study used statistical data to support theoretical analysis and hypothesis testing. By collecting and analyzing relevant statistical data from Yuhang District, Zhejiang Province, it quantified the core elements of ruralization. With the help of SPSS statistical analysis software, the Pearson correlation coefficients between pairs of transformation elements were calculated (Carpio et al. 2021; Juan et al. 2018) and matrix scatter plots of ruralization levels, rural industrial transformation, diversified rural governance, and rural talent gathering at different times were created, adding linear fitting lines to observe trend lines.

Regression Analysis

To delve into the relationship between the level of ruralization and its driving factors, this paper constructed a regression model to study the interactions between three variables, namely, rural industrial transformation, diversified rural governance, and rural talent gathering, and their impact on ruralization levels. It not only revealed the interplay between these variables but also provided quantified measures of their impacts, offering a scientific basis for policymaking.

Case Study

This paper selected Yuhang District as a case study, exploring the practical application of theoretical models in specific contexts through an in-depth analysis of ruralization practices in that area. The case study method made the research more tangible and closer to reality, helping to understand how abstract concepts are manifested and their complexity in practical operations.

Comparative Case Study

By comparing the ruralization practices of Yuhang District with other areas, this study further verified the universality and specificity of the research model. This method can reveal the effectiveness and differences of ruralization strategies in different regions, providing experiences that can be referenced by other areas.

Data Sources and Indicator System

This paper investigated ruralization mechanisms at the county and town levels, emphasizing the contributions of various stakeholders and skilled talents in rural governance. The study focuses on Yuhang District during 2016–2021, utilizing socioeconomic statistics primarily sourced from the “Yuhang District Socio-Economic Statistical Bulletin,” local government departments, and big data of enterprise from the Qichacha website.

Ruralization reflects the efficacy of rural revitalization and the wealth levels of farmers, characterized by the per capita disposable income of rural residents (Y), with data sourced from the annual “Yuhang District Socio-Economic Statistical Bulletin.”

Rural industrial transformation reflects the diversification of nonagricultural industry types and the increase in the number of nonagricultural enterprises (Tingting and Hualou 2015), indirectly represented by the proportion of nonagricultural enterprises to the total number of rural enterprises (X1). These data were collected by the author through big data searches on the Qichacha website, counting the number of nonagricultural enterprises in the rural areas of Yuhang District compared to the total number of rural enterprises. The rural areas here refer to the five towns of Yuhang District, with towns classified as rural and subdistricts as urban areas. Additionally, nonagricultural enterprises are identified based on the industry codes from the Qichacha website. An enterprise is considered nonagricultural if its industry code is nonagricultural. The X2 was calculated using the following equation:where NAE = number of rural nonagricultural enterprises of Yuhang District; and TE = number of rural nonagricultural enterprises.

(1)

Diversified rural governance was gauged through the operating income of village collectives (X2), as outlined in the “Rural Revitalization Strategy Plan (2018–2022)” by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council. This approach suggests a gradual enhancement of the economic power of village collectives and is quantified using data from the Yuhang District Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs.

The gathering of rural talent reflects an increased flow of talent to rural areas to collectively build the countryside, indirectly represented by the number of practical rural talents (X3), with data provided by the Yuhang District Development and Reform Bureau. The indicators and the data involved are given in Table 3.

| Variables | Indicators and the data involved | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per capita disposable income of rural residents (CNY) | |||||||

| Ruralization level (Y) | Rural areas in Yuhang | 31,608 | 34,358 | 37,691 | 41,347 | 44,117 | 48,705 |

| Number of rural nonagricultural enterprises | |||||||

| Degree of transformation of rural industries (X1) | Pingyao Town | 2,213 | 751 | 968 | 1,840 | 1,414 | 1,921 |

| Jingshan Town | 1,502 | 291 | 390 | 580 | 743 | 1,290 | |

| Huanghu Town | 632 | 108 | 144 | 185 | 202 | 218 | |

| Luniao Town | 483 | 197 | 107 | 148 | 145 | 183 | |

| Baizhang Town | 509 | 219 | 168 | 152 | 125 | 146 | |

| Rural areas in Yuhang | 5,049 | 1,566 | 1,777 | 2,905 | 2,629 | 3,758 | |

| Number of total rural enterprises | |||||||

| Degree of transformation of rural industries (X1) | Pingyao Town | 2,293 | 768 | 984 | 1,862 | 1,458 | 1,950 |

| Jingshan Town | 1,711 | 309 | 413 | 593 | 783 | 1,312 | |

| Huanghu Town | 672 | 115 | 164 | 196 | 212 | 231 | |

| Luniao Town | 541 | 207 | 112 | 159 | 167 | 198 | |

| Baizhang Town | 532 | 226 | 175 | 161 | 135 | 153 | |

| Rural areas in Yuhang | 5,749 | 1,625 | 1,848 | 2,971 | 2,755 | 3,844 | |

| Proportion of nonagricultural enterprises to total rural enterprises | |||||||

| Degree of transformation of rural industries (X1) | Rural areas in Yuhang | 0.878 | 0.897 | 0.910 | 0.927 | 0.932 | 0.941 |

| Village collective operating income (million CNY) | |||||||

| Degree of rural diversified governance (X2) | Pingyao Town | 2,432.49 | 2,790.89 | 3,192.74 | 4,161.96 | 5,321.29 | 6,500.97 |

| Jingshan Town | 741 | 801 | 899 | 1,414.11 | 1,552.51 | 2,113.7 | |

| Huanghu Town | 206.23 | 225.46 | 254.1 | 390.68 | 457.94 | 550.74 | |

| Luniao Town | 229.4 | 241.73 | 332.15 | 632.41 | 921.8 | 1,516.79 | |

| Baizhang Town | 165.03 | 171.82 | 219.25 | 450.64 | 656.87 | 841.88 | |

| Rural areas in Yuhang | 3,774.15 | 4,230.9 | 4,897.24 | 7,049.8 | 8,910.41 | 11,524.08 | |

| Number of practical rural talents (persons) | |||||||

| Rural talent gathering (X3) | Rural areas in Yuhang | 15,718 | 16,334 | 17,265 | 18,797 | 21,145 | 22,889 |

Results

Interplays of Industrial Transformation, Diversified Governance, and Talent Gathering

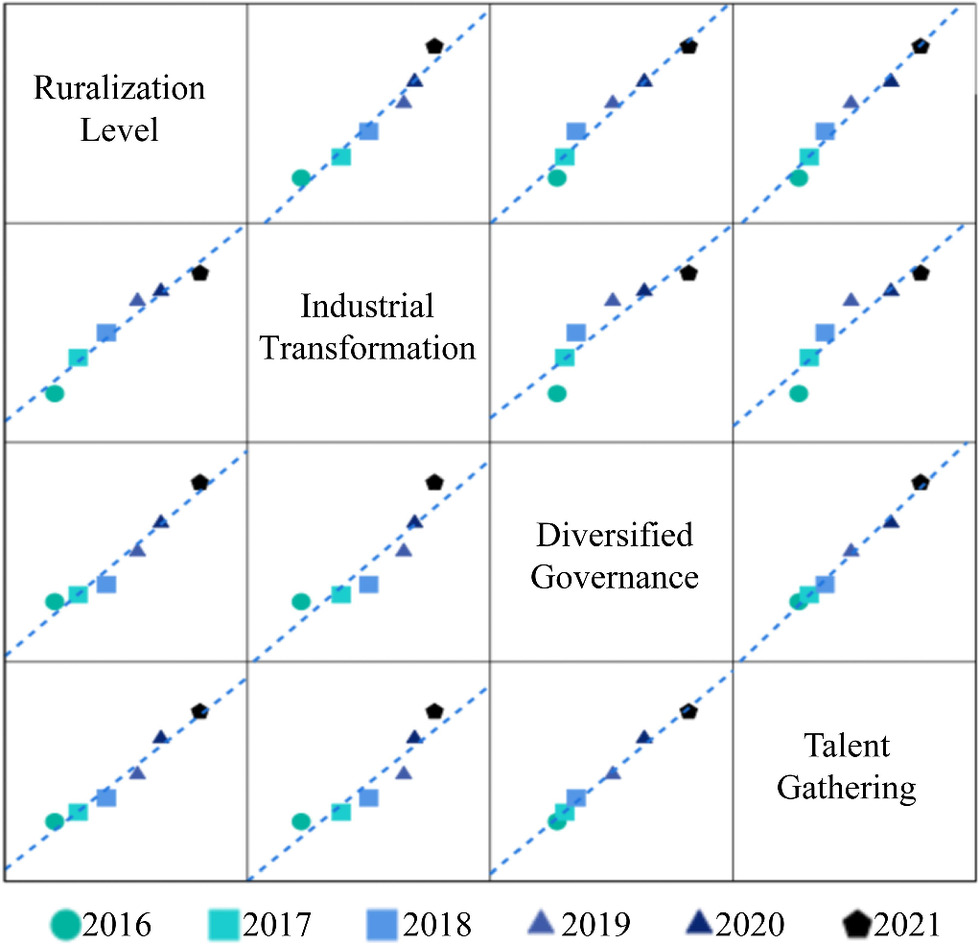

From the results of the Pearson correlation coefficients between the four indicators (Table 4) and the matrix scatter plots with linear fitting lines added (Fig. 9), there is a positive linear correlation between governance and talent, which has steadily increased during the study period. There are positive correlations between industry and talent and between industry and governance, showing a concave curve that is stable at first and then rises rapidly, demonstrating that the development of talent and governance has positively impacted the industry in recent years.

| Variable | Industrial transformation | Diversified governance | Talent gathering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruralization | 0.976** | 0.978** | 0.983** |

| Industrial transformation | — | 0.914* | 0.929** |

| Diversified governance | 0.914* | — | 0.995** |

| Talent gathering | 0.929** | 0.995** | — |

Note: “*” indicates a significant correlation at the 0.05 level (two-sided), and “**” indicates a significant correlation at the 0.01 level (bilateral).

OLS regression analysis was used to analyze the effects of industrial transformation, diversified governance, and talent gathering on changes in the level of ruralization. Putting in all the independent variables will make the model results have the problem of covariance, and the covariance problem is serious after being put together; therefore, to avoid the problem of covariance, three independent models of the impact of industrial transformation, diversified governance, and talent gathering on ruralization were evaluated (Table 5).

| Model number | Variable | Unstandardized coefficients | Standard coefficients | t | Sig. | Collinearity statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard error | Tolerance | VIF | |||||

| 1 | (Constant) | −200,348.716*** (0.002) | 27,041.818 | — | −7.409 | 0.002 | — | — |

| Industrial transformation | 262,543.608*** (0.001) | 29,575.382 | 0.976 | 8.877 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 2 | (Constant) | 25,896.034*** (0.000) | 1,595.302 | — | 16.233 | 0.000 | — | — |

| Diversified governance | 2.042*** (0.001) | 0.219 | 0.978 | 9.317 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| 3 | (Constant) | −1,550.973 (0.708) | 3,855.994 | — | −0.402 | 0.708 | — | — |

| Talent gathering | 2.204*** (0.000) | 0.204 | 0.983 | 10.783 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

Note: ***Indicates statistical significance at the 0.001 level (p < 0.001).

From the multivariate regression model of the impact of industry transformation and talent gathering on ruralization, the level of ruralization increases by 262,543.608 units for every unit increase in industrial transformation. For every unit increase in diversified governance, the level of ruralization improves by 2.042 units. For every unit increase in talent gathering, the level of ruralization increases by 2.204 units. The model equations are as follows:

(2)

(3)

(4)

There is a strong positive correlation between ruralization and the three dimensions of industrial transformation, diversified governance, and talent gathering. The integration and transformation of rural industries, the diversified upgrading of rural governance, and the continuous aggregation of practical rural talent all have a positive effect on increasing the income of rural residents, which in turn drives the ruralization process. The acceleration of the ruralization process also positively influences industrial transformation, rural governance, and talent gathering.

Industrial transformation signifies the optimization and upgrading of the industrial structure in rural areas. New business forms such as rural industry, commercial services, and the integration of agriculture, culture, and tourism industries are rapidly developing. Also, the proportion of nonagricultural industries is increasing. The continuous increase in the nonagricultural degree of the rural industrial structure directly leads to an increase in rural enterprises within the diversified governance system, aggregating enterprise talent, driving the expansion of new rural elite groups, and accompanying increasingly diversified and refined rural governance, and the strengthening of the rural collective economy. The strengthening of the rural collective economy drives employment for farmers, increases investment in various types of rural public facilities, optimizes the rural environment, and further promotes investment attraction and talent recruitment, attracting enterprises and talent aggregation. The aggregation of local sages and new rural elites also attracts more industrial investment, promoting an increase in the operational income of village collectives. Therefore, there is a clear “Industrial Transformation-Diversified Governance-Talent Gathering” mutual feedback mechanism in the ruralization process in Yuhang District.

Rural Industrial Transformation in the Process of Ruralization

Rural industrial transformation is pivotal in enhancing employment and improving the income of low-income groups by transitioning from agriculture to nonagricultural industries as the dominant economic activity. This shift not only aims for the modernization of agriculture but also promotes the integration of local agricultural and natural resources, facilitating a comprehensive industry integration that benefits all sectors. This approach is central to promoting urban–rural coenrichment and sustainable development.

One effective method of rural industrial transformation is the vertical development of specialty agriculture, which integrates the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors. This integration is achieved through strategic resource allocation, thereby enhancing agriculture's multifunctionality and promoting the synergistic development of all three sectors. For instance, DaoDao Agriculture has initiated plans to establish a modern agricultural research base in Huanghu Town to bolster the modernization and upgrading of local agriculture.

Furthermore, the development of agriculture-related industries is also an important method for rural industrial transformation, such as specialty manufacturing, agricultural product processing, handicrafts, tourism, and e-commerce, which leverage local ecological, cultural, and tourism resources. This linkage between agriculture and tourism creates opportunities for leisure agriculture and rural tourism, which have been globally recognized as effective means of rural development. The integration of these industries has proven successful in generating substantial economic benefits for rural areas and enhancing local employment (Augustyn 1998; Fleischer and Felsenstein 2000). A prime example is the emergence of the camping economy around major cities, which has significantly boosted the rural collective economy and facilitated local employment.

In Yuhang District, several towns have adopted innovative approaches to capitalize on their unique resources. Luniao Town, for instance, has developed the Common Wealth Bamboo Garden, attracting urban residents and fostering partnerships with companies like Alibaba for group building, recreation, and tourism activities. Similarly, Baizhang Town is actively developing the Bamboo Literature and Creativity Center in collaboration with urban cultural and creative enterprises to establish an R&D base, effectively merging bamboo resources with cultural creativity. Jingshan Town utilizes its bamboo and tea resources to develop leisure projects like the bamboo tea garden, which has revitalized over 20 unused farm buildings and significantly increased the income of rural residents.

Additionally, the strategy of diversified value integration and development aligns with national incentives to generate rural income, involving venture capital funds, social security subsidies, and employment support mechanisms. This strategic approach helps create special brands and platforms for cultivating science, technology, and talent, thereby improving the rural environment for both production and living.

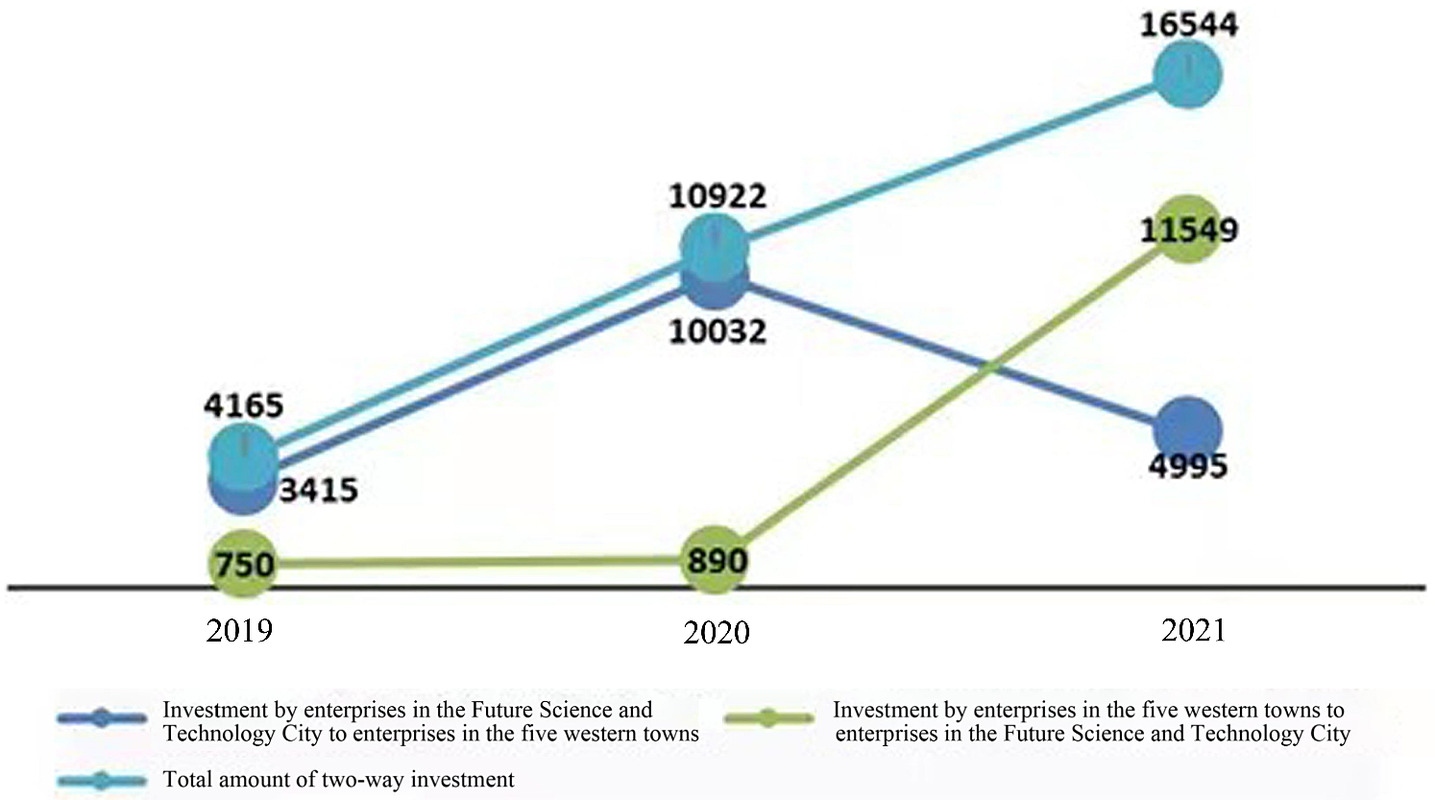

Significant efforts have been made to extend the rural value chain in Yuhang District, where leading enterprises have established R&D centers in urban areas and production bases in rural ones. Projects like the digital factory in Baizhang Town and the Tmall Genie project exemplify this integration. Initiatives such as Babbit Technology’s exploration of a development base and Remote View Network’s development of sloping land resources in Pingyao Town highlight the ongoing efforts to enhance rural industrial development. These initiatives have connected nearly 30 key projects across the urban and mountainous areas of Yuhang District (Fig. 10), demonstrating a successful model of industry chain collaboration between urban and rural settings.

Fig. 10. (Color) Mutual investment in urban and western mountainous areas of Yuhang District, Zhejiang, 2019–2021.

(Data from Enterprise Business Data 2019–2021.)

Diversified Rural Governance in the Process of Ruralization

The shift from monolithic to pluralistic governance in rural areas emphasizes a bottom-up mechanism that enhances rural autonomy and integrates diverse stakeholders into rural development. This model fosters self-sustaining rural communities by encouraging multicentered participation and trust among enterprises, nongovernmental institutions, and local groups. Such diversified governance aligns with antimodern and antiurban sentiments, reflecting a cultural preference for rural values among urban consumers (Gkartzios and Scott 2012; Scott et al. 2017). Traditional rural China often relied on local autonomy and a socialized regional economy, which defined its governance structures (Li et al. 2014). Modern rural development strategies advocate for listening to and respecting the voices of local communities, aligning industrial projects with local sociospatial conditions (Liu et al. 2022), thereby promoting sustainable and endogenous ruralization.

Theoretical frameworks and models from studies, such as the case of Thuringia, Germany, highlight the importance of resource-networks in fostering effective rural development by leveraging social capital and institutional security (Huang et al. 2017). These elements are crucial for ensuring that rural development is participatory and inclusive, catering to the needs and aspirations of local populations (Li et al. 2013). Additional research underscores the role of institutional safeguards and the introduction of social capital in recent rural development (Binns and Nel 2003; Bjørnå and Aarsæther 2009; Lowe et al. 1995).

In practice, despite the tendency of rural governance to default to a traditional single governance model driven by township government or village committees, there is a concerted effort to mitigate the challenges posed by the top-down national strategy for rural revitalization. This strategy often neglects villagers’ spiritual needs and vernacular characteristics, an issue highlighted by recent studies (Geng et al. 2023). National strategies and local action plans are increasingly encouraging a more integrated approach, involving businesses and local entities to bridge urban resources with rural development needs (Wu et al. 2019). This process is exemplified in Yuhang District, where village-run enterprises and “commonwealth workshops” support local industry development and job creation. For instance, Xiaogucheng Village has adopted the democratic deliberation method of “four deliberations and six steps,” facilitating effective self-governance. Additionally, the “Village Dream Maker” initiative in Yuhang attracts young entrepreneurs with international experience to contribute to local development, illustrating a practical application of community-driven rural revitalization.

These examples underscore a shift toward a governance model that is not solely dependent on hierarchical, top-down approaches but rather fosters collaborative, multiparty participation that strengthens rural self-governance and aligns with the contemporary socioeconomic trends in rural development.

Rural Talent Gathering in the Process of Ruralization

Talent is crucial in revitalizing rural industries, where ruralization involves gathering individuals motivated by a return to their roots, the lure of industry prosperity, and government policies supporting rural talent. This influx of talent into rural areas promotes the development of industrial agglomerations, enhancing the material space and living conditions to attract professionals across various sectors. Marx posits that human actions are driven by material motives, which, in rural contexts, means enhancing the environment to attract and retain high-end researchers and skilled workers (Geng and Maimaituerxun 2022). Additionally, the economic theory of economic man suggests that rational decision-making in profit or utility maximization aligns with rural incentives that address the social and cultural dynamics of rural societies, defying straightforward economic logic.

In practice, Yuhang District exemplifies effective talent integration strategies by hosting regular events to attract high-level talents to its western mountainous areas, deepening collaborations with academic institutions like Zhejiang University and Zhejiang Agriculture and Forestry University. This fosters a flow of talent and resources toward rural development, as shown by initiatives such as the Honey Pear Science and Technology academician workstation. The district has also innovated a new model of talent attraction termed “working and living in five towns in the west of Yuhang District and contributing to the service in the whole province,” focusing on industries such as large health, digital economy, and cultural and creative industries to accelerate the gathering of innovative professionals.

The concept of rural nostalgia inspires diverse populations to contribute to rural development, leading to the return of urbanized individuals and the emergence of young entrepreneurs (Chen and Kong 2022). Yuhang District supports this movement by fostering young agripreneurs, establishing provincial-level farms for young entrepreneurs and creating a coalition of young entrepreneurs. This environment encourages innovation and supports the involvement of local farmers in activities such as agricultural processing and cultural tourism, aiming for comprehensive local employment and entrepreneurship.

Moreover, the role of traditional cultural elements like the “Township Sage Culture” in rural development is significant. Yuhang District’s “Return of Township Sages” project leverages these cultural dynamics to promote investment and development in rural areas, establishing a sage association and a contact system for key sages that encourages new generations to invest and build in their hometowns. This blend of modern talent strategies with traditional cultural values is pivotal in fostering sustainable rural development and revitalizing local communities.

Comparative Rural Practices between Yuhang and Other Regions

In 2021, Yuhang District, with 40% of its area as nonplain, reported a GDP of 250.22 billion yuan. Anji County, covering 25% nonplain area, had a GDP of 56.63 billion yuan and is noted for its high environmental quality, embodying the concept that “lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets.” Yunhe County, with only 5% nonplain area, had a GDP of 9.81 billion yuan and is celebrated for its mountainous terrain and traditional woodcarving (Fig. 11). Table 6 highlights the ecological and economic disparities among the regions.

Fig. 11. (Color) Sketch map of Anji County and Yunhe County.

[Base map by the Standard Map Service system of the China Ministry of Natural Resources, No. GS (2023)2767.]

| Regions | Administrative area (km2) | Population (10,000s) | GDP (billion yuan) | Urbanization rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuhang | 942 | 130.9 | 2,502.2 | 72.9 |

| Anji | 1,886 | 59.5 | 566.3 | 61 |

| Yunhe | 989.6 | 12.9 | 98.06 | 71 |

Data from Anji and Yunhe were analyzed using the Yuhang linear fit model to assess their ruralization, industrial transformation, diverse governance, and talent aggregation. The results, detailed in Table 7, reveal that in Anji, the model accurately predicts the relationships between ruralization, industrial transformation, and talent aggregation, but performs poorly in predicting those involving diverse governance. In Yunhe, the model effectively predicts relationships involving diverse governance and talent aggregation but is less accurate in predicting interactions involving industrial transformation. This analysis demonstrates varying applicability of Yuhang’s model across different regional contexts.

| Object of comparison | Anji | Yunhe | Anji | Yunhe | Anji | Yunhe | Anji | Yunhe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Y | X1 | X2 | X3 | ||||

| Actual values | 39,495 | 24,555 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 41,694 | 1,672 | 15,000 | 14,860 |

| Predictive model | Y = f(X1) | X1 = f(Y) | X2 = f(Y) | X3 = f(Y) | ||||

| Predicted values | 40,690 | 3,581 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 6,660 | −657 | 18,623 | 11,845 |

| Predictive model | Y = f(X2) | X1 = f(X2) | X2 = f(X1) | X3 = f(X1) | ||||

| Predicted values | 111,034 | 29,311 | 1.18 | 0.87 | 7,646 | −10,521 | 19,174 | 2,336 |

| Predictive model | Y = f(X3) | X1 = f(X3) | X2 = f(X3) | X3 = f(X2) | ||||

| Predicted values | 31,509 | 31,200 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 4,263 | 4,112 | 49,690 | 12,599 |

Discussion

Empirical Analysis of Ruralization under Urban–Rural Disparity

Data collection and measurement in rural areas, compared to urban settings, present distinctive challenges. This study, which relies on indicators collected over 6 years, required additional validation to confirm their effectiveness in depicting aspects such as industrial transformation, diversified governance, talent aggregation, and overall ruralization. The availability of relevant data at the county level or below is often limited, with crucial economic and social development indicators typically only accessible at national or provincial levels, as seen in sources like the “China Rural Statistical Yearbook.” Furthermore, the indicators chosen to represent key variables such as rural industrial development, scale of enterprises, and levels of social governance are not comprehensively covered in local yearbooks and reports. Additionally, although data directly from government departments are more accessible, changes in administrative structures and organizational shifts mean that only 6 years of data could be collected, impacting the study’s scientific rigor and reliability.

To overcome these data collection and monitoring challenges in rural settings, several strategies can be implemented: (1) enhance cooperation and coordination by establishing a local-level data collection network, fostering partnerships between local governments, academic bodies, and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) to create a comprehensive database and a regional data-sharing platform; (2) promote public involvement by encouraging local community members and village collectives to participate in gathering data, potentially through surveys or mobile applications; (3) integrate official and unofficial data sources, combining governmental statistics with information from NGOs and business reports to develop a complete understanding of rural dynamics.

Applicability of Ruralization Models under Different Conditions

Comparative analysis reveals similarities and differences in the ruralization practices of Yuhang, Anji, and Yunhe. Variations in resource availability, historical heritage, and cultural backgrounds influence the adaptability of Yuhang's ruralization model to other regions. Anji County aligns well with Yuhang in terms of industrial transformation and talent aggregation due to similar approaches to developing a green economy and attracting talent with favorable policies. However, Anji shows a mismatch in diverse governance, possibly due to its reliance on traditional agriculture or tourism, contrasting with Yuhang's industrial-focused economy. Yunhe County's practices align closely with Yuhang in diverse governance and talent aggregation, sharing similar economic activities like tourism. However, discrepancies in industrial structures lead to a lower match in predicting industrial transformation. To enhance the model's adaptability, it is suggested to customize economic classifications and support policies, adjust local governance structures, and develop tailored talent aggregation strategies to fit local conditions better.

In Anji County, the ruralization model is well-suited to areas like industrial transformation and talent aggregation, reflecting similar development patterns to Yuhang. Nonetheless, its application to diverse governance is less effective due to differences in economic activities and reliance on agriculture or tourism. This indicates a need for regional customization in governance strategies and economic focus.

Yunhe County shows good compatibility with Yuhang's model in governance and talent strategies, benefiting from shared approaches in economic activities. However, differences in industrial focus result in lower compatibility in predicting industrial transformation outcomes, suggesting a need for a more tailored approach to industrial development and policy adaptation.

Overall, to improve the Yuhang model's effectiveness across different regions, it is essential to analyze specific economic activities, refine governance structures, and diversify talent strategies to better meet local socioeconomic conditions and enhance regional development.

Summary of Ruralization Practices across Multiple Regions

Comparing the ruralization development models of Yuhang with those of Anji and Yunhe in Zhejiang (Fig. 12), it can be observed that Yuhang's ruralization development feedback mechanism is also applicable to Anji and Yunhe, albeit with slight innovations tailored to the specific circumstances of Anji and Yunhe. Additionally, the rural development experiences of Anji and Yunhe can provide effective references and insights for other rural areas.

Anji County and Yunhe County, despite differing ecological conditions and economic levels, have showcased the value of strategic planning and efficient resource use in ruralization. By centralizing resources and optimizing allocation, they have aligned economic and social development in rural settings. Adapting strategies to local conditions, Anji County has leveraged its bamboo resources to bolster its economy and promote sustainable environmental practices. Additionally, investments in infrastructure improvements have enhanced villagers’ quality of life, boosted tourism, and stimulated service industries. These initiatives offer valuable lessons for other rural areas on achieving sustainable rural development by implementing holistic strategies, fostering community involvement and local governance, and harmonizing environmental conservation with economic growth.

Suggestions for Sustainable Development of Yuhang Ruralization

To sustain the ruralization process in Yuhang District, it is essential to implement strategic measures for rural development. This includes reforming the household registration system to expand urban public services, advancing rural collective property rights reform to optimize land and asset management, and establishing mechanisms for the market-oriented circulation of property rights with robust supervision. Additionally, enhancing support systems involves issuing district-level policies for entrepreneurship and employment, developing a diversified financial system to increase rural financial services, and strengthening policy implementation and supervision to ensure effective management and support for low-income populations. These efforts aim to promote equitable resource distribution and efficient policy synergy, ensuring the progress of ruralization in Yuhang District.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In summary, the new urbanization strategies in urban areas create conditions for revitalizing rural towns in mountainous areas. For instance, the ruralization process in Yuhang, through collaboration between urban and mountainous rural areas, has typically exhibited a “Industrial Transformation–Diversified Governance–Talent Gathering” feedback mechanism by jointly promoting rural industry innovation, strengthening mountainous area investment attraction, advancing diverse rural governance, and fostering talent concentration to accelerate the ruralization process in Yuhang's mountainous regions. The following suggestions are offered for other similar regions interested in advancing ruralization to bridge urban–rural divides, reduce regional disparities, and narrow gaps in income, thereby promoting shared prosperity.

Promote Rural Industry Transformation and Stimulate Self-Sustaining

Enhance communication networks in mountainous areas to support innovative industries and enable remote work and R&D. Construct digital and technological bases to integrate agriculture, culture, and tourism, focusing on specialty products like tea, bamboo, and forestry. Promote technology entrepreneurship to increase agricultural income and develop commercial strategies, including boutique travel and green tourism. Strengthen the homestay industry, enhance branding, and use live streaming and exhibitions to market agricultural products and cultural resources. Innovate in forestry by promoting utilitarian forestry, creating economic forestry processing parks, advancing forest-based creative industries, experimenting with small tree adoption models, and developing forest carbon sinks for a carbon trading economy.

Promote Innovative Governance and Explore Revenue Mechanisms

Promote village–enterprise cooperation through resource integration and collective development models, enhancing rural communities and village companies. Boost e-commerce for agricultural products and optimize rural industrial parks with a “base + industry + fund” model to support green finance and industrialized agriculture. Revitalize cultural spaces by transforming idle factory buildings into cultural parks and creating shared offices to stimulate innovation.

Attract Rural Talent and Activate Developmental Dynamics

Direct intellectual resources to mountainous areas by hosting high-level talent events and creating talent hubs through dual-creation parks and collaborations between universities and localities. Implement innovative talent introduction strategies, support youth entrepreneurship, and train agripreneurs and new farmers. Establish local elite associations and “Youth Entrepreneur Alliances” to attract investments to hometowns. Improve public services and educational resources in mountain towns and increase salaries for agricultural professional managers to enhance their focus on village economic development.

Yuhang's ruralization mechanism not only addresses agricultural challenges but also drives urbanization by revitalizing mountainous areas with ecological and cultural wealth, showcasing a sustainable rural development model. This approach leverages the potential of these areas for collaborative urban-rural development in industry, entrepreneurship, and talent. Like Anji and Yunhe, Yuhang’s model could face limitations in less resource-rich regions. Future research will aim to refine data collection and explore ruralization models tailored to diverse regional conditions.

Data Availability Statement

All data, models, and codes generated or used during the study appear in the published article.

References

Abdul-Wakeel Karakara, A., and I. Dasmani. 2019. “An econometric analysis of domestic fuel consumption in Ghana: Implications for poverty reduction.” Cogent Social Sci. 5 (1): 1697499. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1697499.

Aksoy, T., A. Dabanli, M. Cetin, M. A. Senyel Kurkcuoglu, A. E. Cengiz, S. N. Cabuk, B. Agacsapan, and A. Cabuk. 2022. “Evaluation of comparing urban area land use change with urban atlas and CORINE data.” Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (19): 28995–29015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17766-y.

Araghi, F. 2012. “The invisible hand and the visible foot: Peasants, dispossession and globalization.” In Peasants and globalization, edited by A. Haroon Akram-Lodhi and Cristóbal Kay, 111–147. New York: Routledge.

Augustyn, M. 1998. “National strategies for rural tourism development and sustainability: The Polish experience.” J. Sustainable Tourism 6 (3): 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589808667311.

Bakari, S., and M. El Weriemmi. 2022. “Which is the best for Tunisian Economic Growth: Urbanization or Ruralization?” Munich Personal RePEc Archive. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/112208/.

Baron, H., A. E. Reuter, and N. Marković. 2019. “Rethinking ruralization in terms of resilience: Subsistence strategies in sixth-century Caričin Grad in the light of plant and animal bone finds.” Quat. Int. 499: 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2018.02.031.

Binns, T., and E. Nel. 2003. “The village in a game park: Local response to the demise of coal mining in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.” Econ. Geogr. 79 (1): 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2003.tb00201.x.

Bjørnå, H., and N. Aarsæther. 2009. “Combating depopulation in the northern periphery: Local leadership strategies in two Norwegian municipalities.” Local Gov. Stud. 35: 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930902742997.

Botes, L., and D. Van Rensburg. 2000. “Community participation in development: Nine plagues and twelve commandments.” Community Dev. J. 35 (1): 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/35.1.41.

Carpio, A., R. Ponce-Lopez, and D. Lozano-García. 2021. “Urban form, land use, and cover change and their impact on carbon emissions in the Monterrey Metropolitan area, Mexico.” Urban Clim. 39: 100947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100947.

Chambers, R. 1994. “Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Challenges, potentials and paradigm.” World Dev. 22 (10): 1437–1454. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(94)90030-2.

Chen, M., Y. Zhou, X. Huang, and C. Ye. 2021. “The integration of new-type urbanization and rural revitalization strategies in China: Origin, reality and future trends.” Land 10 (2): 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020207.

Chen, N., and L. Kong. 2022. “Rural revitalization in China: Towards inclusive geographies of ruralization.” Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 12 (2): 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221102933.

Datta, A. 2015. “New urban utopias of postcolonial India: ‘entrepreneurial urbanization’ in Dholera smart city, Gujarat.” Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 5 (1): 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820614565748.

Fleischer, A., and D. Felsenstein. 2000. “Support for rural tourism: Does it make a difference?” Ann. Tourism Res. 27 (4): 1007–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00126-7.

Geng, Y., L. Liu, and L. Chen. 2023. “Rural revitalization of China: A new framework, measurement and forecast.” Socio-Ecol. Pract. Res. 89: 101696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2023.101696.

Geng, Y., and M. Maimaituerxun. 2022. “Research progress of green marketing in sustainable consumption based on CiteSpace analysis.” Sage Open 12 (3): 21582440221119835. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221119835.

Ghosh, S. n.d. “The avery review: Notes on rurality or the theoretical usefulness of the not-urban.” https://averyreview.com/issues/27/notes-on-rurality.

Ghosh, S. 2022. “In what sense ruralization?” Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 12 (2): 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221102947.

Gillen, J., T. Bunnell, and J. Rigg. 2022. “Geographies of ruralization.” Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 12 (2): 186–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221075818.

Gkartzios, M., and M. Scott. 2012. “Gentrifying the rural? Planning and market processes in rural Ireland.” Int. Plann. Stud. 17 (3): 253–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2012.696476.

Gururani, S. 2020. “Cities in a world of villages: Agrarian urbanism and the making of India’s urbanizing frontiers.” Urban Geogr. 41 (7): 971–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1670569.

Hansen, A. 2018. “Meat consumption and capitalist development: The meatification of food provision and practice in Vietnam.” Geoforum 93: 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.05.008.

Hu, Z., Y. Wang, Y. Liu, H. Long, and J. Peng. 2016. “Spatio-temporal patterns of urban-rural development and transformation in east of the “Hu Huanyong Line”, China.” ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 5 (3): 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi5030024.

Huang, H., Y. Guiqing, M. Philipp, and L. Hannes. 2017. “Post-rural urbanization and rural revitalization: Can China learn from new planning approaches in contemporary Germany.” City Plann. Rev. 41 (11): 111–119.

Juan, W., L. Yajuan, L. V. Li, H. U. Jing, and Z. Xiang. 2018. “Hotel competitiveness evaluation and spatial pattern based on internet data: A case study of high-end hotels of Wuhan urban area.” Prog. Geogr. 37 (10): 1405–1415. https://doi.org/10.18306/dlkxjz.2018.10.010.

Lankoski, J., and A. Thiem. 2020. “Linkages between agricultural policies, productivity and environmental sustainability.” Ecol. Econ. 178: 106809. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106809.

Lewis, W. A. 2013. Theory of economic growth. 1st ed. London, UK: Routledge.

Li, T. M. 2010. “To make live or let die? Rural dispossession and the protection of surplus populations.” In The point is to change it: Geographies of hope and survival in an Age of crisis, edited by N. Castree, P. Chatterton, N. Heynen, W. Larner, and M.W. Wright, 66–93. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Li, Y., Y. Liu, and H. Long. 2012. “Characteristics and mechanism of village transformation development in typical regions of Huang-Huai-Hai plain.” Acta Geogr. Sin. 67 (6): 771–782.

Li, Y., Y. Liu, H. Long, and W. Cui. 2014. “Community-based rural residential land consolidation and allocation can help to revitalize hollowed villages in traditional agricultural areas of China: Evidence from Dancheng County, Henan province.” Land Use Policy 39: 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.02.016.

Li, Y.-r., Y.-s. Liu, H.-l. Long, and J.-y. Wang. 2013. “Local responses to macro development policies and their effects on rural system in China’s mountainous regions: The case of Shuanghe village in Sichuan province.” J. Mountain Sci. 10: 588–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-013-2544-5.

Lin, G., X. Xie, and Z. Lv. 2016. “Taobao practices, everyday life and emerging hybrid rurality in contemporary China.” J. Rural Stud. 47: 514–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.05.012.

Liu, J., X. Zhang, J. Lin, and Y. Li. 2022. “Beyond government-led or community-based: Exploring the governance structure and operating models for reconstructing China's hollowed villages.” J. Rural Stud. 93: 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.10.038.

Lowe, P., J. Murdoch, and N. Ward. 1995. “Networks in rural development: Beyond exogenous and endogenous models.” In Beyond modernisation, edited by J.D. Van der Ploeg and G. van Dijk, 87–105. Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum.

Ma, W., G. Jiang, W. Li, and T. Zhou. 2018. “How do population decline, urban sprawl and industrial transformation impact land use change in rural residential areas? A comparative regional analysis at the peri-urban interface.” J. Cleaner Prod. 205: 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.323.

Marsden, T. 2010. “Mobilizing the regional eco-economy: Evolving webs of agri-food and rural development in the UK.” Cambridge J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 3 (2): 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq010.

Mathias, B. D., H. Hutto, and T. A. Williams. 2024. “Amish brain gain: Building thriving rural communities through a creation perspective toward work.” Bus. Horiz. 67 (2): 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2023.12.003.

McGee, T. G. 2002. “Reconstructing ‘the Southeast Asian city’ in an era of volatile globalization.” In Critical reflections on cities in Southeast Asia, 31–53. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

McGee, T. G. 2013. “9 the emergence of Desakota regions in Asia: Expanding a hypothesis.” In Implosions/explosions, edited by B. Neil, 121–137. Berlin, Boston: JOVIS.

Murdoch, J. 2000. “Networks—A new paradigm of rural development?” J. Rural Stud. 16: 407–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(00)00022-X.

Olfert, M., and M. Partridge. 2010. “Best practices in twenty-first-century rural development and policy.” Growth Change 41: 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2257.2010.00523.x.

Parsons, L., and S. Lawreniuk. 2022. “Geographies of ruralisation or ruralities? The death and life of a category.” Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 12 (2): 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/20438206221102937.

Richardson, D. 2017. Vol. 1 of International encyclopedia of geography, 15 volume set: People, the earth, environment and technology. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Roy, A. 2016. “What is urban about critical urban theory?” Urban Geogr. 37 (6): 810–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1105485.

Ryser, L., and G. Halseth. 2010. “Rural economic development: A review of the literature from industrialized economies.” Geogr. Compass 4 (6): 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00321.x.

Scott, M., E. Murphy, and M. Gkartzios. 2017. “Placing ‘home’and ‘ family’ in rural residential mobilities.” Sociologia Ruralis 57: 598–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12165.

Tingting, L., and L. Hualou. 2015. “Analysis of rural transformation development from the viewpoint of ‘population-land industry’: The case of Shandong province.” Econ. Geogr. 35 (10): 149–155.

Woods, M. 2007. “Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place.” Prog. Hum. Geogr. 31 (4): 485–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507079503.

Wu, B., L. Liu, and C. Carter. 2019. “Bridging social capital as a resource for rural revitalisation in China? A survey of community connection of university students with home villages.” J. Rural Stud. 93: 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.05.008.

Yuhang District Government. 2022. Statistical Communiqué on the National Economic and Social Development of Yuhang District, Hangzhou, 2022. http://www.yuhang.gov.cn/art/2023/3/28/art_1229247534_4152367.html.

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Copyright

This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

History

Received: Jan 21, 2024

Accepted: Jul 15, 2024

Published online: Oct 17, 2024

Published in print: Mar 1, 2025

Discussion open until: Mar 17, 2025

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Download citation

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.