Traditional Chieftaincy in Sotouboua, Togo: A Land Regulation Institution on the Front Line of Urban Planning Challenges

Publication: Journal of Urban Planning and Development

Volume 150, Issue 1

Abstract

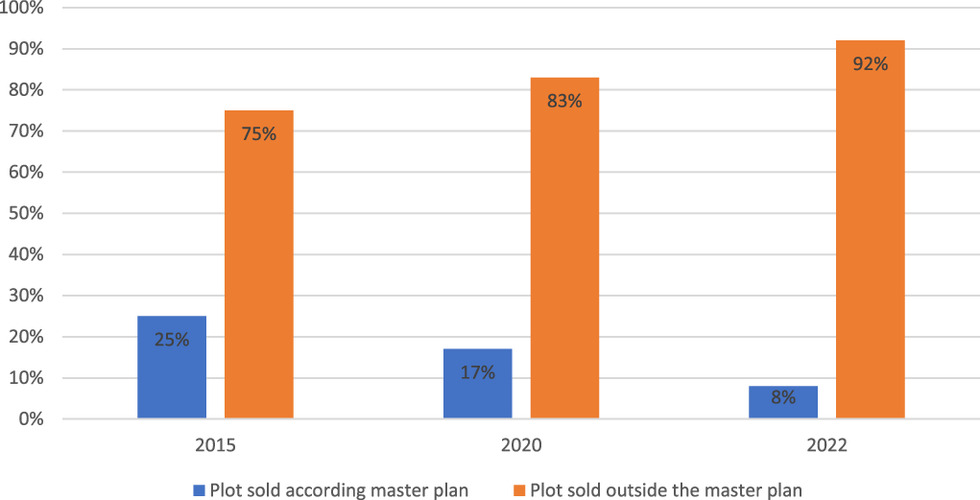

This study allowed us to understand the challenges and issues related to the problem of planning and land management in Sotouboua, Central Region, Togo, through the prism of the intervention of traditional chiefs. The nature of urban planning in Togo tends to be based on northern standards and methods but without significant impact. This study draws on recent empirical research that examines the activities of traditional leaders on urban land development. Although land use planning that is based on state control has limited practical impact, urban land tenure is physically structured and planned by urban dwellers who aspire to establish legitimate forms of tenure through customary authorities. Out of 75% of the subdivision operations in 2015 and 92% in 2022 that were carried outside the master plan, traditional chiefs are involved in 64% and 87.5% of land transactions, respectively. Therefore, chiefdom occupies a central place in land transactions. All land transactions are subject to the scrutiny of traditional chiefs, who become intermediaries in land exchanges. Therefore, the participatory approach to urban planning should be reshaped to involve traditional leaders in decision-making and even in conceptualization. The challenges range from the institutional and administrative frameworks of urban planning to land rights and contradictions that are inherent in land use planning.

Introduction

For many decades, researchers, public actors, and regional and international institutions have been highlighting the pace at which cities are growing in Africa and its implications for development (Silva 2012). Although it is true that the increase in the proportion of the population that lives in urban versus rural areas is less rapid in Africa than it is sometimes claimed (Cohen 2004), urban growth has generally been extremely high in recent decades (Fox 2012). Over the last two decades, the continent has shifted to unprecedented urban growth. The urban population is estimated to reach 1.2 billion by 2050 (UN-Habitat 2018, p. 30). The observation is simple: in the world and Africa, human settlements are extensive and have a much lower average density than in the past (Antoni and Youssoufi 2007; Simard 2014). These settlements now evoke anarchy, insecurity, poverty, or massive urbanization. This growth implies many questions about urban planning and management to accommodate the population and offer a better living environment from a sustainable perspective.

Urban planning has been implemented in African cities since the 1900s in its nascent form under colonial administration and continued after independence (Sondou 2020). Although the state is still responsible for planning and regulating land use, the town halls and private actors must implement these plans (Hartmann and Spit 2015). However, after several years of urban planning, the results have fallen short of expectations. Indeed, the galloping urbanization since 1990, with an average natural growth rate of 4% per year, has generated socioeconomic, environmental, and political problems. From social, inequalities are becoming increasingly spatial, and the two reinforce each other to promote regimes of territorial segregation and spaces of violence, pollution, congestion, and anarchy. For justice and equity, cities suffer from urban disorder, the infernal mechanism of informal and precarious housing, difficult accessibility, and a very poor quality urban environment.

Because land is special goods, it is one of the most constitutionally protected in most countries (Hartmann and Needham 2012; Vejchodská et al. 2022). However, land ownership and property rights regimes vary from country to country and depend on the legal and institutional frameworks that are in place. The desire to capture revenues from urban land transactions has led to shifting dynamics in the primary control over land and maneuvering in peri-urban land markets in most cities in Sub-Saharan Africa. Some studies attribute land use changes to indiscriminate land sales by some chiefs (Arthur and Dawda 2015; Fuseini 2016). In particular, Siiba et al. (2018) examined the role of chieftaincy and sustainable land use planning in Yendi and observed that chiefs are increasingly taking center stage in land use allocations. Land use planning in West Africa is largely a function of the state; however, approximately 70%–80% of land allocation and transaction operations emanate from communities, private individuals, and chiefs who are the custodians of custom and practice. The link between traditional leaders and land governance means that the former is increasingly used to study or evaluate the latter. The extent of land consumption in cities in West Africa for occupation and the emergence of dispersed, low-density housing raise questions about the efficiency and sustainability of land use.

As in most colonized African states, land governance, land use and urban planning systems in Togo are largely modeled on colonial administrative systems of state control (Aholou and Sondou 2021; Korbéogo 2021). The urban planning system tends to undermine traditional leadership models, such as chieftaincy, which predates colonialism in Africa (Marrengane et al. 2021). Chieftaincy, a traditional governance system with a chief, queen, mother, and several traditional leaders, depends on the territory involved, which controls a specific group of people or land exists and functions (Boateng and Afranie 2020). The chief performs several functions, which include that of custodian of customary law and natural resources (Asaaga 2021). With the status of community leaders, mediators, and guarantors of societal values, chiefs prevent these subjects from cultivating, feeding injustice and hatred, or both. They are mediators, guides, and, better still, scouts who facilitate the social evolution of the people. This posture justifies the trust that the traditional institution enjoys from the governed. In addition, traditional land access mechanisms or settling disputes are sometimes more operational, economical, and accessible than modern law. In addition, the customary system of land ownership is rooted in African societies, and chieftaincy continues to be powerful in the management of cities (Adjei-Poku et al. 2023). Therefore, it would be appropriate to question traditional chieftaincies on their role in allocating and distributing land for a wide variety of uses. This is all the more urgent since, according to Ouedraogo (2014, p. 20): “(…) more than fifty years after independence, no serious reflection has been made on the role and place of chieftaincy constructively. It is simply presented as a scarecrow that can undermine the foundations of democracy and national cohesion.”

International trends in land use policy in developing countries tend to emphasize the importance of recognizing and harnessing local land tenure systems to achieve rational land management in the context of multiple norms. According to Adjei-Poku et al. (2023), the weakening of traditional land use and governance in Kumasi is a major cause of ineffective urban planning in most African countries. Similarly, in Malawi, the failure of the state to take into account the interest of the chieftaincy in land reforms has negatively affected its implementation (Chikaya-Banda and Chilonga 2021). This means that chieftaincy institutions are critically important for land use planning and change. Enemark (2010) and Nyalewo et al. (2022) examine the evolution of the concept of land management and recognize a shift in discourse from technical aspects to a broader discussion on the role that chieftaincies play in land governance. However, little empirical or theoretical treatment of these concerns exists in Togo. To address this gap, local decision-making on land use and planning in Togo, a secondary city in Togo, is examined in this study.

In Togolese cities, anarchic occupation of urban spaces exists. This dynamic of the spontaneous colonization of these spaces is part of a set of symptoms of global change that have taken on a rapid and dangerous pace (Lüdeke et al. 2004). This is becoming increasingly noticeable, especially in secondary cities such as Sotouboua, where the constant population growth generates the expansion of spatial occupation, giving a prestigious financial and social value to land resources (Dossou and Dahande 2014). This demographic growth is at the origin of the spatial expansion of the city into the adjacent peri-urban and rural areas (Sondou 2020). In this context, land becomes a real vector for investment and wealth accumulation. The result is increased competition for access to land. Land, which used to be a collective and inalienable asset, is now subject to significant changes (Nyalewo 2020; Nyalewo et al. 2022).

Questioning the spatial structure of urban planning and the land market is part of the process of reflection on the recomposition of territories and the most relevant spatial, social, and environmental issues in territorial governance (Vandermotten and Govaerts 2002). The poor land governance that characterizes the research environment results in the anarchic and disorganized occupation of urban, peri-urban, and rural spaces and urban expansion that is not very coherent. These different observations lead us to reflect on the modalities of land management that facilitate human settlement when organizing the urban space and preserving the environment. To achieve this, the following questions need to be answered: (1) how and why do chiefs contribute to these land use changes and the transformation of the morphology of the city of Sotouboua despite the legal and institutional arsenal of land use and management regulations; (2) in other words, what is the role of traditional chieftaincy institutions in the urban development of Sotouboua; (3) do they play a more passive role in urban planning processes; and (4) are they involved in the realization of land use plans. We hypothesize that the role traditional chieftaincy plays depends on the particular institutional arrangements in place for land management in Togo. The objective of this study is to critically examine the involvement of traditional leaders in land transaction processes, which uses lessons learned from the recent expansion of Sotouboua in Togo. The rest of this study is structured as follows. First, the presentation of the area is presented, followed by the methods in this study. Next, the results and discussions focus on land planning and governance, general causes, the chiefdoms’ share of land transactions, and livelihood issues are presented. This study ends with the concluding sections that provide a summary and implications.

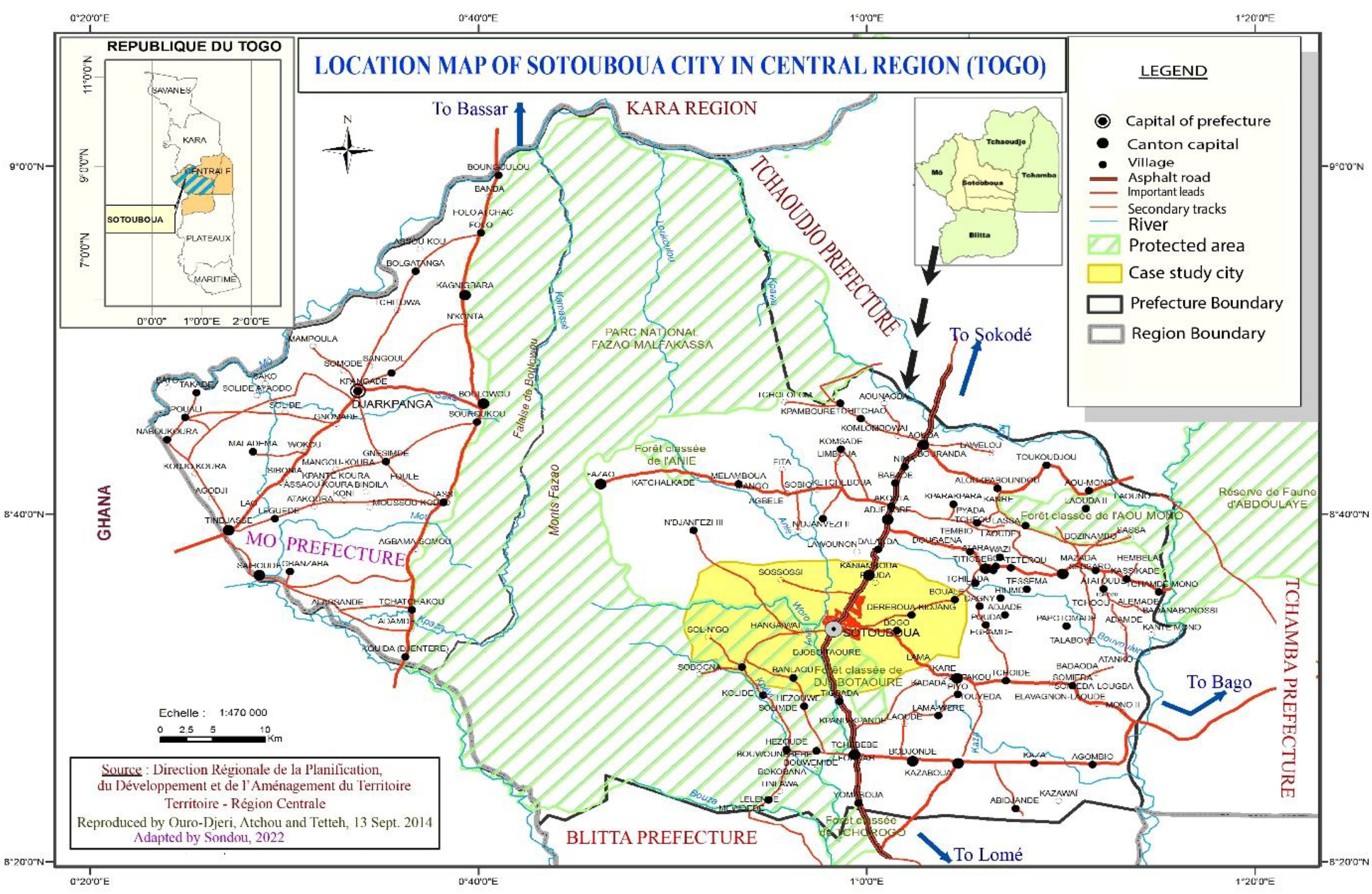

Sotouboua: Area Study

This study was conducted at Sotouboua, which is in the heart of the central region of Togo. Sotouboua was focused on, because it has experienced one of the largest increases in large-scale land acquisition over the last decade. It is an area with agricultural potential and has had appropriate guidelines for land acquisition and a seed farm since 1977. Of note, land problems have become even more visible following the installation of the CECO construction company in the city (Sotouboua, Region centrale, Togo). The town is approximately 287 km from Lomé the capital of Togo and 52 km from Sokodé, the main town in the central region (Fig. 5). Sotouboua community has 10 neighborhoods, such as Laou, Laouwai, Lokou, Pyo, Père Perrin, Sékendéria, Sondè, Tchitchao, Watchalo, Werida, and Zongo. However, it has swallowed up two nearby localities: (1) Kaniaboua to the north; and (2) Déréboua to the east. This situation is due to the high rate of land occupation and population growth. In the first general population census that was carried out between 1958 and 1960, the town of Sotouboua had 4,664 inhabitants. The population of the town rose to 6,699 and 10,578 inhabitants in 1970 and 1981, respectively, in the second and third general population and housing censuses. According to the results of the fourth general population and housing census (INSEED-Togo 2010), the town of Sotouboua has 23,030 residents. It is estimated to have 42,405 in 2020.

Research Methodology

This study is qualitative research based on the socioanthropological survey method. After the exploration of documents and interviews, participant observation was carried out. The documentary research focused on books, articles, the results of symposia, planning, land management, and urbanism. It is necessary to recall that all the documents confirmed the existence of an abysmal gap between the projects and the results in their conception, realization, and appropriation. To understand these gaps, we went through the actors. Interviews were conducted with resource people who are experts in gathering information on the involvement of traditional chiefs. Seven categories of actors were interviewed, including two canton chiefs (one regent), 15 neighborhood and village chiefs, 16 landowners, six surveyors, three urban planners, four canvassers, and two agents of the territorial and local authorities. Participatory observation was carried out in the field and with resource people. During the data collection phase, we did not seek to saturate the data given the reason and subjective choice of respondents. The results were transcribed manually through a codification based on the following subthemes: (1) urban planning tools; (2) urban land management; (3) the involvement of traditional leaders in urban operations; (4) participation in the development of tools; and (4) impact of land issues on planning.

Conceptually, Bettalanffy’s (1971) general systems theory provides an appropriate framework to compare the mutual interdependence of land policy, sustainable development, and integrated land use management systems. In the general systems theory, where everything affects everything else, the transboundary effects of local and regional policies on land and related resources are similar, which have now assumed considerable importance. Therefore, local policies are no longer seen in their isolationist context but within the broader framework of constraints and opportunities that are offered by information technologies. The organizing process at work emanates from the game of actors. By the theory of the actor’s game, it is appropriate to retain the formal and informal exchanges, the conflicts of interest that arise from the confrontation of ambitions that intersect and overlap or oppose. As a common factor and denominator in the elaboration and execution of social and economic policies, the collaboration or opposition of actors offers a glimpse of the deployment of the perceptions and representations of the protagonists on everything that concerns land governance and planning.

Urban Planning in Togo

Urban planning was regulated during the German colonial period. The first urban planning document dates from 1913. It was drawn up at the instigation of the German Governor August Köhler for the city of Lomé. The road network of the current city center was defined by this document. However, in 1930, Article 1 of Decree No 257 1930 enacted the urban planning and hygiene measures for the city of Lomé. This stipulated that all types of constructions should be built with durable materials, such as baked bricks, stone, lime, cement, and iron and intended to demolish all buildings or dwellings of fortunes assigned to temporary economic activities, such as boards, palms, and sheets. This measure was extended to all urban centers in Togo in 1935. Article 1 of Decree No 267 1935 stipulated that no construction could be built, transformed, demolished, or undergo major repairs without authorization that was issued by the district chief. In addition, this decree stipulated that all buildings should have rainwater drainage systems, toilets, urinals, and sewage systems. The efforts of the colonial administration aimed to preserve the aesthetic image of the cities and the quality of the urban environment. At the end of its independence, the Togolese authorities aligned themselves with the logic of the colonists by adopting a multitude of texts that regulated urbanization. The fundamental text for urban planning in Togo is Decree No. 67-228, October 24, 1967, which relates to urban planning and building permits in urban areas. This text expresses the need to establish a master urban plan for all the country’s urban areas. The latter would be divided into zones according to their use and nature, which included constructions. Therefore, in Togo, urban planning considers: (1) Law No. 2017-008 June 29, 2017, on the creation of communes; (2) Decree No. 2017-144/PR December 22, 2017, that establishes the territorial jurisdiction and chief town (administrative center) of the districts of the Maritime and Savanes Regions; and (3) Law No. 2016-002 June 4, 2016, on the framework law on land use planning that gives the guiding principles of land use planning. The subdivision must comply with the provisions of the master urban plan (Article 37 of the 1967 Decree) and be subject to the prior authorization of the Minister of Public Works (Article 36 of the 1967 Decree). The state, for a variety of reasons, has opted for a centralized urban planning policy. All decisions related to planning, development, and housing are taken at the central level. Urban planning tools are developed by the central government without consulting the population. Several institutions have been created for the effective implementation of these provisions. These include: (1) the Order of Surveyors of Togo, which groups together the liberal professional surveyors who have the monopoly conferred by law to draw up plans and topographic documents that delimit landed property and the rights attached to the Directorate of Planning, Equipment and Agricultural Mechanization (DAEMA), which is involved in formalizing rural land ownership; (2) the General Directorate of Urban Planning and Housing (DGUH), which has become the General Directorate of Urban Planning, Municipal Development, Housing, and Real Estate (DGUDMHPI). It intervenes in the same way as DAEMA when formalizing rights. It operates in urban areas. Its role is primarily to draw up the master plan and monitor its implementation. The DAEMA and DGUDMHP are the directorates that deal with the approval of the second visa on the plan that is drawn up by the surveyor; (3) the Department of Land and Cadastral Affairs, which manages all the administrative and technical documents that describe the landed property. Its mission is summarized in four main points: (1) land; (2) technical; (3) documentation; and (4) fiscal missions. Through its land mission, the cadastre is responsible for the final approval of all plans, whether urban or rural. The DGUDMHP is the main institution that is responsible for preparing urban plans, as can be deduced from Decree No. 67-228 October 24, 1967, on urban planning. One of its primary objectives is to provide all regional and prefectural capitals and semiurban centers with more than 5,000 inhabitants with planning documents, which include master, detailed urban, and subdivision plans.

Town of Sotouboua and Its Urban Planning Tools

The town of Sotouboua has been the subject of graphic documents and provisional urban plans for over three decades. The first urban planning document dates from 1977. It was drawn up by the General DGUH. The graphic and provisional urban planning documents of the city are: (1) the restitution of the aerial photographs Institut Géographique National du Togo (1976) and Ministère de l'Administration Publique et de la sécurité (1996); (2) the aerial photographs taken by the MAPS geosystem in February 1996; (3) the Urban Master Plan that was produced by the Direction General d’Urbanisme in 1977; (4) Extension Plans 1 and 2 made by the General DGUH in 1977 and 1981; (5) the plan of the state of the town of Sotouboua carried out by the Cabinet de Topographie et de Dessin (CA.TO.DES.) August 2011, the plan of Extension No. 3 carried out by the Urbanisme, Architecture Ingenierie Design and Construction, Architecture, Urbanisme et Salubrité de l'Environnement research departments (2004); and (5) the Master Plan for Urban Planning and Development (2011), which is a revision of the Master Plan (1977). The Plan Directeur d'Urbanisme, which is defined as a short–medium and long-term planning tool, makes it possible to set the fundamental guidelines for the occupation and use of land and the development objectives for a given territory in a vision that is shared with various concerned actors. To make the master plan of the town of Sotouboua operational, three extension plans were drawn up. These plans provided development proposals and policies to better control the urban sprawl in the town of Sotouboua and to offer the urban and rural populations a better living environment. The land policy guidelines up to 2030 are through the master plan for development and urban planning that was approved in 2015. This document defines Sotouboua’s land use policy and determines activities to promote sustainable land use. Analysis of the data from the field reveals land use problems. The objectives were set in urban policy documents, and the results were divergent. In addition, from a global perspective, little research exists on land use policy adjustments and the potential impact of urbanization. Therefore, Huang et al. (2022) indicate the need to combine several methods in the planning process when collecting recommendations and referencing policies regarding future change predictions. Studies have shown that the population of Sotouboua is quite young, with a relatively high level of education. It has almost all the necessary capacities to carry out administrative functions and economic activities. Agriculture dominates the local economy. Sotouboua’s agricultural production represents approximately 12% of the national agricultural production. Its market is ranked as the country’s largest grain market, ahead of Guérin-Kouka’s. Its influence goes far beyond the limits of Togo thanks to its seed farm. It is a dynamic city for trade; however, its fiscal capacity remains marginal. Decree No. 67-228, October 24, 1967, on the approval of urban planning documents in Togo, stipulates that the implementation of land use policy must be planned in future sectorial policy planning documents. Despite this provision, the city of Sotouboua is faced with serious problems, which include the management of urban land, that hinders its harmonious development.

Urban Land and its Management in the Town

The city of Sotouboua is characterized by the domination of customary law, which is a set of unwritten legal rules that are applied to land, over modern law that is based on written legal rules. Although the city benefited from a master plan very early (1977), spatial practices remained typically traditional for a long time, with a mode of acquisition in transition. Today, the mode of acquisition by inheritance is losing ground, and land is acquired more by purchase from customary owners, surveyors, and canvassers. These actions, which are carried out without considering the urban planning schemes, explain the more or less irregular pattern that is observed in the new districts. The state is almost absent in the procedures for the subdivision of lots. The lots defined are mostly 600 m2 and cost between CFA 400,000 and CFA 1 million. Neither the state or the community intervenes in the trade and regulation of the land market. Although these plots were acquired by purchase, most of the owners only have proof of their ownership in a simple receipt of sale and deed of acquisition that is signed by the canton chief.

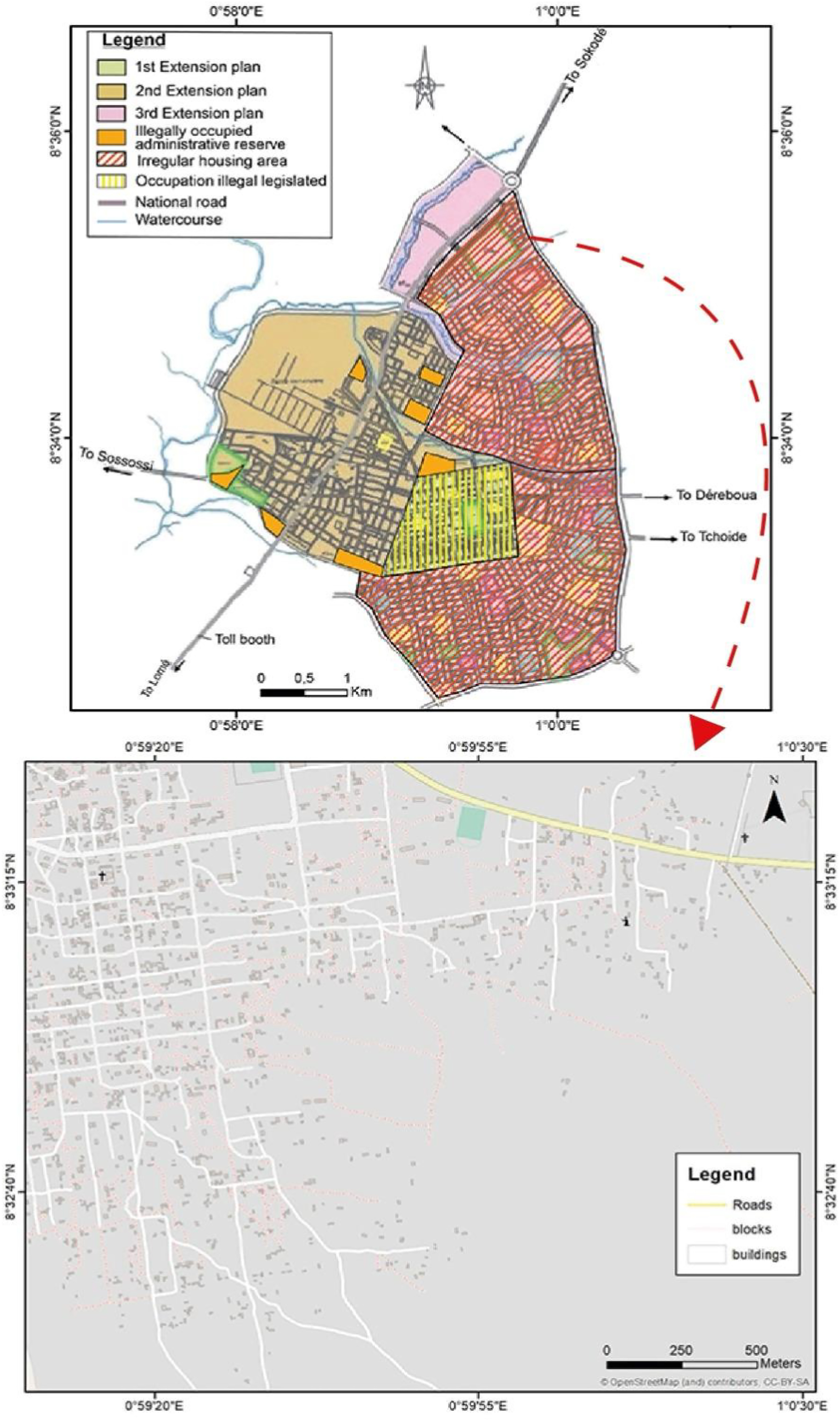

Therefore, urban land is made available to buyers through subdivisions that do not always consider the pace of spatial evolution of the city. Considering its current population, Sotouboua is out of the master plan that was drawn up 30 years ago; however, the subdivisions go beyond the limits of this plan. These subdivisions are a good deal for speculators and contribute to the abnormal expansion of the urban area and the pushing back of cultivable land to the distant peripheries. Overall, 75% of the subdivision operations in 2015 were carried out without considering the guidelines of the master plan shown in Fig. 1. In 2020 and 2022, this proportion was 83% and 92%, respectively. The occupation of space is now performed ahead of planning efforts. The administrative reserves that will house the urban facilities are poorly considered when parceling out. This is due to ignorance or inconsideration of the Decree of March 16, 1995, which sets the proportion of land for residential use at 50% and that reserved for public facilities at 50%. In addition, after a certain period, some administrative reserves are divided and redistributed by the transferor or the authorities as soon as they realize that no infrastructure is planned for the area.

Of note, a large proportion of the operations have been carried out in full view of the traditional chiefs. This state of affairs creates a deep malaise in the management of urban space. Therefore, land operations are left to the mercy of a pilot at sight without any forward-looking vision. These anarchic and illegal practices are the consequence of the irregular construction that is observed in all neighborhoods, especially in the new ones, such as Watchalo and Père Perrin (Fig. 6). Under Decree No. 67-228 October 24, 1967, all developers in Togo must transfer 50% of the surface area of the land to be subdivided to the municipality, free of charge, before the sale of any lots, to create land reserves for the installation of public facilities (e.g., roads, urban networks, social, or cultural facilities). This provision has proved essential to put into practice some of the land allocations for public facilities, as set out in the Master Plan for Urban Development [Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement et d’Ubanisme (SDAU)] for Sotouboua town. However, in the absence of immediate development of new public facilities or networks, these hollow spaces have become popular areas for illegal occupation, construction, or uses, such as building houses (Fig. 6). The occupation of these areas poses problems for the availability of land for public interest and community facilities. Fig. 6 shows that not all planned spatial structures, roads, and buildings. have been respected. The subdivisions that orient the spatial development of the city are in two directions: (1) the northeast; and (2) the east, on either side of the RN12 (Sotouboua–Bago–Kambolé road) that passes through Déréboua. The urban fabric has exceeded the limits provided for in the first two extension plans (Extensions No. 1 and 2) without any formal standards, therefore compromising the execution on the ground of Extension Plan No. 3.

The anarchic parceling out of land is now leading to local public policies to regularize a posteriori these urban extensions. This is the case with Extension Plan No. 2. Under social pressure from the residents of these new districts, the state services, the national operators in charge of urban networks, and the local authorities have been forced to intervene on an ad hoc basis, all too often in a sector-based and disorganized manner. This is for the development–consolidation of local access roads or partial installation of urban networks (e.g., water, sewerage, electricity, and public lighting). In addition, because these postconstruction public interventions are extremely costly for the ratio between the cost of road and network development and the low density of built-up areas involved, they lack overall coherence on a municipal scale, because they are not currently prioritized spatially in these neighborhoods between the various competent authorities. This fait accompli policy encourages the continuation and expansion of land speculation and the development of illegal housing estates.

To the west of the city, the Anié River, the vast domain of the administrative center west of the Route Nationale (National Road), and the domain of the late President Eyadema south of the Sotouboua–Sossé road between the Anié River and Sondé Public Elementary School, which constituted obstacles to the extension of the city, were crossed and illegally occupied. This lack of control and public organization of urban expansion explains the nonlinear spread of housing. These housing estates were built without ensuring a satisfactory connection with existing or planned roads or urban networks, as shown in Fig. 6. The result is haphazard development that is totally disconnected from the existing road and urban networks. Most of the land was divided into lots and sold to individuals. Although these plots were acquired by purchase, most owners only have proof of ownership as a simple receipt of sale with recognition by the customary actors, such as the arrondissement or village chiefs and not necessarily the canton chief. The subdivisions are increasing and are clandestinely made by private surveyors who have not considered the data in the plans. In most cases, they do not know the plans. However, these subdivisions have increased the value of urban land in the locality. This increase in value encourages increased land speculation and deprives many households of the region’s primary wealth (e.g., arable land). The city is expanding without respecting the plans. Anarchy has taken hold in the occupation of space, particularly in peri-urban areas, due to spatial growth and the inaccessibility of urban centers for modest populations (Cisse 2018). The legal and technical responsibility of land management institutions and actors has increased because their level of knowledge and ownership influences urban policies.

Implications of Traditional Chieftaincy in Urban Land Transactions in Sotouboua

Land policy choices have an impact on the development of territories. Land policy is a form of government intervention in markets that are related to land (Davy 2012). Land policies attempt to achieve various environmental, social, and economic goals. These goals are not always explicitly framed as land policy goals, and they are sometimes incorporated into land use planning or environmental policies. For example, they include providing adequate land protection from excessive development and sprawl (Liu et al. 2016), densification and land thrift, and providing land for affordable housing (Crook et al. 2015; Shahab et al. 2021).

How a society defines property rights to land and natural resources, distributes them among different actors, and secures and administers them is indicative of how a society is managed (Deville and Durant-Lasserve 2008) and how the city evolves. The Togolese land tenure system (a juxtaposition of modern and customary law) is an important factor in the production of urban space. It generates a form of syncretism that favors a game for the actors, each seeking to take advantage of the most favorable situation (Jacquemot 2013). Thanks to the multiple parallel land channels that are run by customary owners, intermediary developers and city dwellers who wish to access the property, access to urban land is ensured in defiance of urban planning ethics and urban development plans (Ministère de l’Urbanisme et de l’Habitat 2010). The problems that are related to land are due to the absence of a land information system. The involvement of the canton chief in land purchases increases annually, and the weight of the first owners continues to decrease. In land purchases in the town of Sotouboua, there is a strong involvement of traditional chiefs, as shown in Fig. 2. A large proportion of respondents (63%) believed that the township chief has the legitimate authority to authenticate plots. To date, the land remains in the hands of local owners.

The land remains in the hands of local communities, not rich foreigners who have everything required to buy land from the poor, and only the customary authorities can authenticate the owner and register the transaction (interview with KM on December 20, 2022). Therefore, the land tenure system is characterized by a lineage-based management for rural and urban land. In the traditional Gourmantché land management system, there is no land chief (Zoma and Djolgou 2022); the clan, family chiefs, or both hold customary rights to land. Each family exercises property rights over its territory, the boundaries of which are recognized by the other families. The township chief is the key actor in all land transactions in this scheme. Further analysis of the chart shows that chiefs are involved to varying degrees in all community land transactions. In 2015, the canton chief was involved in 34.7% of land transactions, compared with 13.9% for village chiefs and 19.4% for neighborhood chiefs. In 2022, the graphical breakdown of the level showed that the canton chief was involved in more than 70% of the deeds of sale, compared with 12.5% for village chiefs and 5% for community chiefs. The chiefs have played an important role in these processes, because they are the guardians of the land. Therefore, access to land (e.g., loan, purchase, lease, and donation) is always between the owner and the beneficiary with the involvement of the village chief (Zoma and Djolgou 2022). Customary authorities, particularly the township chief, have been major contributors to the large-scale land acquisition processes on the continent (Gasparatos et al. 2015). Chiefs often act as gatekeepers to large-scale land acquisitions and help foreign donors, investors, and the state steer the institutional landscape of land tenure, which is complicated and prone to social conflict (Ahmed et al. 2018). They sign the land sale contracts and conciliate conflicting parties. The agreements related to access to land are oral agreements, and a deed of sale is delivered by a traditional chief (village or canton). Sometimes, this is carried out via a Procès-Verbaux de cession de site for public utility facilities (e.g., schools, livestock markets, stores, and shallows). However, they often engage in such land acquisition processes in a counterproductive manner, deeply affecting their outcomes.

These deficiencies and dysfunctions, combined with insufficient awareness of the legal practices that need to be observed, force the majority of populations to conduct their land and real estate transactions underground and illegally, which contributes to the emergence of precarious neighborhoods and the uncontrolled spatial expansion of urban centers. Gouamene et al. (2019) identified two modes of access to land in Daloa: (1) access to land by the town hall; and (2) access to land by private land development, which refers to land developments that are initiated by village communities and landowners under the auspices of traditional leaders. These conclusions are confirmed by Alla (1991) and corroborated by Adou et al. (2017), who argued that illegal occupations are the preferred mode of land access in Daloa. This mode of access represents 80% of the land access rate. According to Yao et al. (2018), in the villages integrated into the city of Daloa in Côte d’Ivoire, 80% of allotments were opened on plots that had been the subject of transactions between Indigenous Bete and non-native peoples of Daloa (allochthones and allogènes) or between Indigenous people and private operators (Yao et al. 2018, p. 142) with the endorsement of customary authorities. Among the 29 allotments that were built between 2001 and 2010, Gouamene et al. (2019, p. 290) indicated that village allotments accounted for 79.31% compared with 20.69% of administrative allotments. Between 2012 and 2020, subdivisions made by communities without the approval of the local (mayor’s office) and central authorities accounted for 87%, with the share of administrative subdivisions representing 13%. In addition, irregular allotments are flourishing alongside authorized allotments. Therefore, more than 80% of the allotments that were made in Sotouboua between 2012 and 2020 are irregular compared with the 20% that were approved by the country’s land management services. In this land use pattern, a lot of land is bought and remains uncultivated, which distorts habitats. This spatial expansion escapes the authorities that are in charge of local land management, therefore creating pressure on agricultural land resources, which results in a spatial, structural, and functional disorder that gives the city an unfinished appearance. This land production, which should be the responsibility of the state, has been imposed as the master of the urban game, and subdivisions have been performed through the DGUH and the town halls.

The main advantage of using customary land rights through intermediaries is the recognition that this type of right represents an indisputable guarantee in the area of land, which is guaranteed by traditional leaders. Ordinance No. 12 February 6, 1974, to the Land and Domain Code in Togo, which sets out the rules for acquiring ownership of urban land, implicitly consolidates customary rights and gives landowning communities the opportunity to initiate the subdivision of their plots. Law No. 2018-005 June 14, 2018, of the Land and Property Code in Togo stipulates in Article 6 paragraph 3 that the state “guarantees the property rights of individuals and communities acquired according to customary rules.” This provision now places customary and private owners at the heart of land production.

The private and public production of land for housing and economic activities requires their involvement. In their prerogatives as guarantors of habits and customs or as actors in development, the district, village, and community chiefs are under the umbrella of the public authority and administer the land in their territorial jurisdiction according to the accepted rules. However, they do not have an official register of notes or an unofficial register of operations, apart from a few instructions in a notebook of the transactions they have had to record and the meetings they have attended. Previously, land and customary chiefs or traditional leaders allocated land use rights according to community conventions (Durand-Lasserve 2004); however, their role has evolved. Today, they sign sale agreements for payments ranging from CFA 5,000 to CFA 10,000, with some gifts depending on the generosity of the buyer. According to several people interviewed, this situation stems from the precariousness in which these authorities live, leading them to sign any paper as soon as it can bring them a discount. Therefore, this situation is akin to passive corruption of space (i.e., an agreement between landowners, traditional chiefs, and surveyors to continue parceling and selling). This process of fragmentation poses problems, particularly for Indigenous populations, who are gradually seeing their large domain reduced to a few barely standing family huts and fields, which are miles from their homes.

Urban Planning: A Fundamentally Contradictory Approach

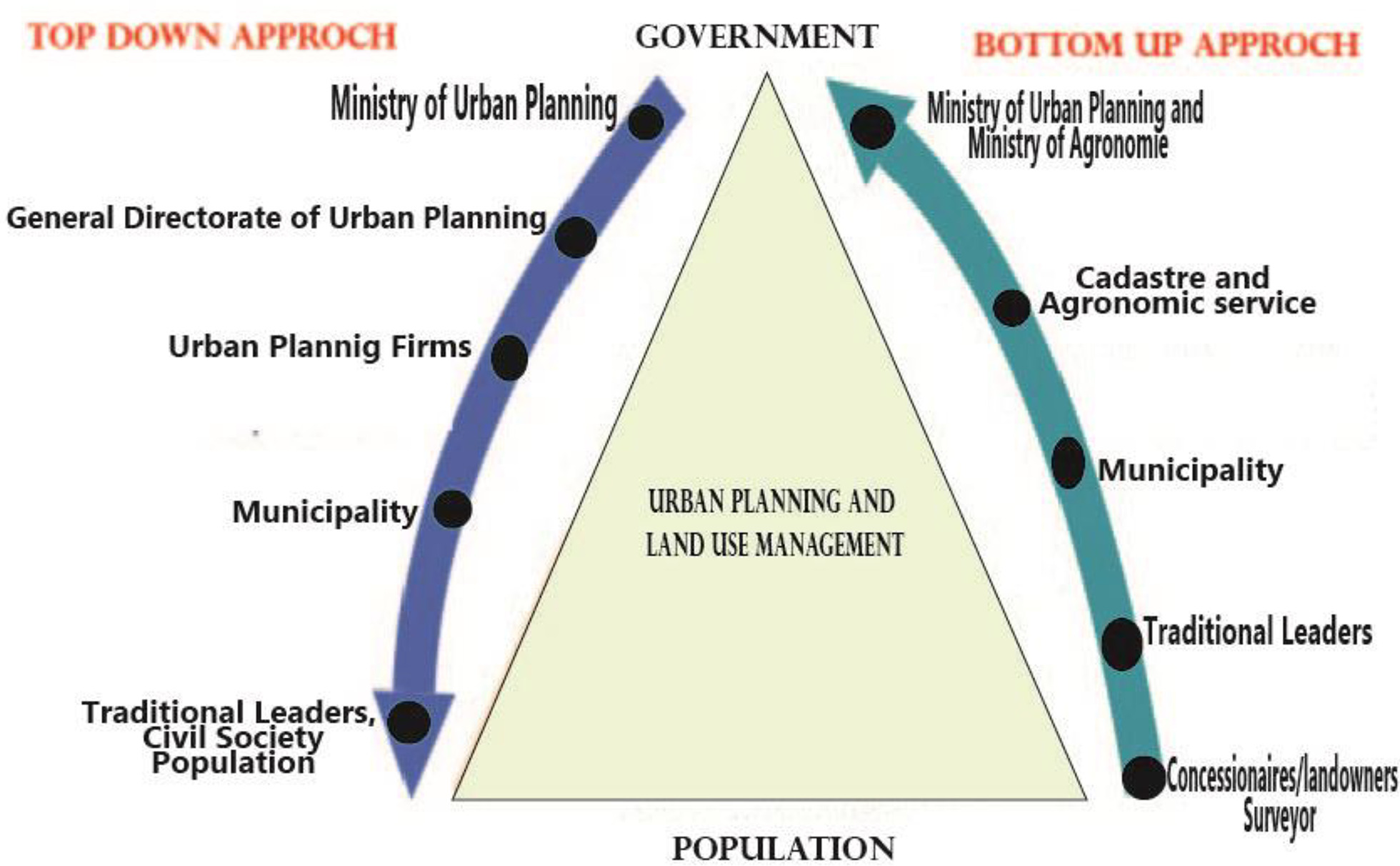

Under customary law that applies to land use, no community member has the right to allocate or sell their family land to a stranger without informing the village, ward, or township chief. Although the land in question might not belong to the chief, they must be informed, because all land disputes are first presented to traditional leaders before being brought before the formal courts. If the user wants to claim the land that has been given or sold to them, the traditional leader will be a very important witness and arbiter of such matters at their level. This is a bottom-up approach.

However, spatial planning is characterized by its top-down approach. The decision-making is very vertical, centralized, and hierarchical. It is restricted to a few key actors who hold a high degree of legitimacy. On the one hand, elected officials and decentralized state services hold political power; on the other hand, the planners hold the information and technical expertise. The top-down approach involves the traditional actors in planning: the political leaders (the State, ministries, and urban planning department) and the planners who act as experts. The practice of this spatial planning gives the image of a very bureaucratic style: the elaboration is a technical matter that is settled between experts and the state structure without really opening the arenas of negotiation to private actors or civil society (Sondou 2020; Lou 2017). The process focuses more on the orientations and less on the means that are associated with implementation. From a practical point of view, the main criticisms focus on implementing the developed plans (Liao 2019) and, therefore, on a certain inability to move from planning to decision-making to implement actions to achieve the objectives and carry out various projects.

Top-down planning is an approach that aims to move progressively from the top to the bottom levels of a hierarchy. Bottom-up planning, on the other hand, is to develop a plan of action at an operational level of the hierarchy and then develop it to the next level. Therefore, from the bottom-up to the top-down, as shown in Fig. 3. The thought that decisions made at the center would be strictly enforced has sometimes led to incomplete policies. In the rational legal management model, public servants try to achieve their objectives. However, with the increase in studies on the implementation phase of public policies, the three principles are not fully adopted. This is because the actors in the implementation phase (e.g., the civil servants) cannot always remain neutral on all issues; they have value systems, and the appointees have relative autonomy. In this case, where the decision comes from the center and its implementation is not supervised, the functioning of the policies could be modified and interpreted differently by the implementing actors.

The emergence of differences and dysfunctions in the stated purposes and practices of public policy began with the evaluation of Weber’s ideal bureaucracy in the organizational sociology studies of Merton, Selznick, and Blau, which started in the 1940s. Wildavsky and Pressman (1984), famous for their work Implementation, pointed out why a decision made by the central government could not be executed as required by the local government. The actors in the implementation phase (the civil servants) could not always remain neutral on all issues; they had their value systems, and the appointees had relative autonomy. In this case, where the decision comes from the center and its implementation is not supervised, the functioning of the policies could be modified and interpreted differently by the implementing actors.

As Chenal (2013) said with humor, urban planning in African cities is reminiscent of the video game SimCity. Everything seems possible, and the recipes for a good city are simplistic. The urban reality is less so: demographic growth and territorial expansion, poverty, environmental degradation, and informality in a significant portion of urban activities. All questions that challenge urban planning, in its approach and its aims, and the participants in charge of managing the present and thinking of the future of the African city. The government mainly concentrates more on the conception and how to make public policy and forgets the crucial part of implementation. There is a very big difference between the conceptualization of public policy and its implementation. The authors suggest that for any project to be successfully implemented, the conception of the policy needs to address all the issues involved, for instance, from conceptualization, successful implementation, and proper accountability (Chenal 2013). However, this must not just dwell on conception, which is usually true in most government projects. (Wildavsky and Pressman 1984, p. 56). In this state, only the effective participation of field actors, such as traditional chiefs, could contribute to the efficient observation and monitoring of the territory.

Participation of Traditional Chiefs in the Development of Urban Planning Tools

Actions for better living together would tend more toward the collective definition of desired or desirable futures, with a view to improving the quality of life and strengthening social, environmental, and economic equity. In particular, they would be based on renewed participatory democracy, active subsidiarity and good governance, and innovation in institutional engineering and process architecture (Bertrand 2004). The participatory approach is an official procedure that is valued by the decision makers and conceptual actors that are involved in territorial development. In planning, it calls for defining urban problems with all the actors and, in particular, with the traditional chiefs. In the town of Sotouboua, the plans were drawn up through consultation with all the actors. But, as one informant pointed out, “We were only called once for a meeting with the planning team, I think. They made us understand the procedures, but for the rest of the work, we didn’t know anything until 2016 when we were called to come and say that the minister was there to submit the plan to the local authorities. We don’t know if we have a role in this story.”

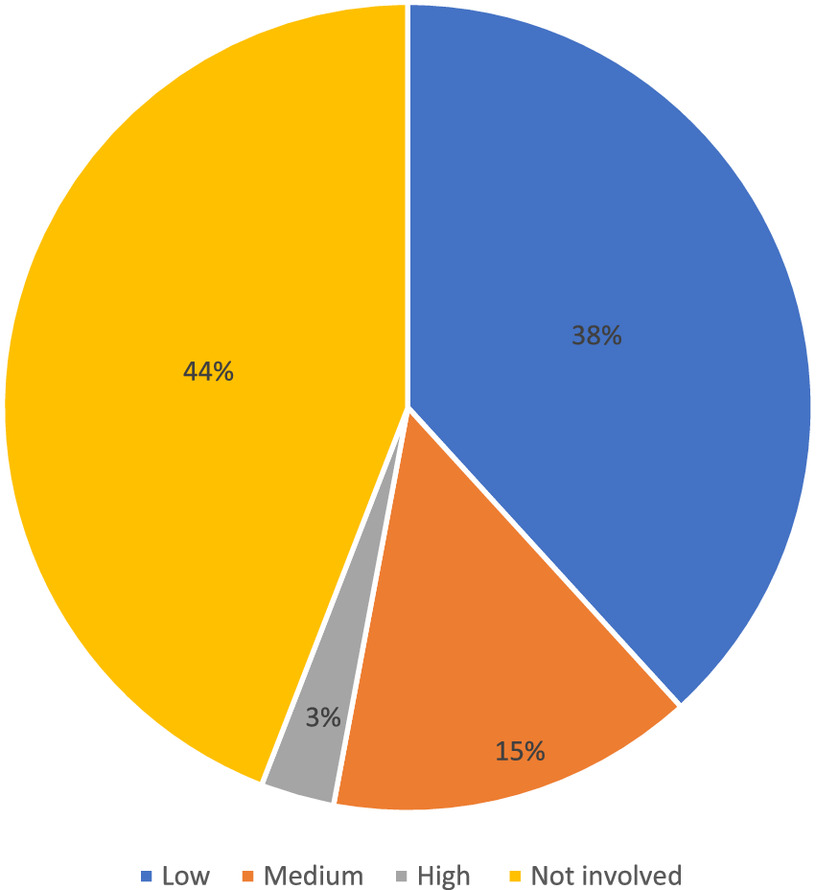

These reported remarks reflect the state of blatant ignorance of the role of traditional chiefs in land regulation and, by extension, in urban planning. Whether they are the plan sponsors or the planners, the role of these actors eludes them. Traditional leaders are confined to their role as guarantors of customs and traditions. Their role as negotiators between landowners and public authorities in the provision of land for basic urban facilities, such as classrooms and community centers, in the communities is ignored. This made Ndong (2017) say that consultation with the population has become a custom for all decision makers, except that the decisions have often already been taken. It is fair to say that the degree of involvement of traditional leaders is at the root of their lack of concern for the impacts of land issues on urban planning. For Chorfi (2019), the issue of “participatory urban planning through consultation and citizen participation in the development of urban planning instruments is completely missed,” the popular actor is completely ignored. The lack of interest of the state services that are in charge of the mandatory consultation has made the instrument a document established by the initiation of the design office without popular consultation. The consultation is limited to some structure that does not care about the problems of the inhabitants. The graph (Fig. 4) opposite shows the level of involvement of traditional leaders in the procedures for drawing up the grand plan for the town of Sotouboua.

Fig. 4 shows that 44% of the guarantors of the customs and practices in the Town of Sotouboua were not involved in developing the master plan. Out of a sample of 34 respondents, only 3% felt that they were strongly involved in the process, 15% felt that they were moderately involved, and 38% felt that they were weakly involved. The comparison of an urban planner to a doctor demonstrates the logic that drives the authorities that are responsible for developing urban planning tools to exclude users and city leaders in the process of their design. Indeed, “the planner functions like a doctor. He diagnoses you and presents you with the results of the diagnosis. Afterwards, he shows you the ways and means by which you will have to heal yourself” (Field survey with MC, August 2020). Therefore, the city of Sotouboua is seen as a sick individual, and the urban planner is the doctor. In the medical field, the patient does not intervene in the diagnosis; therefore, logically, the population of Sotouboua should not intervene in the development of the plan.

Fig. 5. (Color) Physical setting of the town of Sotouboua.

(Adapted from Ouro-Djeri et al. 2014.)

Fig. 6. (Color) Map that shows the irregularity of land use.

(Adapted from Augi 2011. Map data © OpenStreetMap and contributors, CC-BY-SA.)

Impacts of Land Tenure Problems on Urban Planning

Land tenure problems have overturned all the plans that have been adopted to date in the town of Sotouboua. These problems have negative repercussions on the space and population of the town. It should be recognized that the art of designing the city is not given to everyone, but its nonunderstanding and inapplicability have harmful consequences on the urban soil. According to the information gathered, land problems are the primary cause of family breakdown and the loss of social cohesion. This situation is due to the disproportionate sale of urban and rural land to foreigners since 2005, most of whom were in Lomé before the postelection crisis. They have monopolized several plots when their descendants survive in the rentals, which is a source of tension between parents and their offspring. The irregular division of space prevents the town hall and the public works departments from laying out long roads and implementing urban services in the places foreseen by the plans. In addition, they are obliged to postpone projects on the outskirts, which increases the distance between the facilities and the beneficiaries.

Land insecurity impacts the natural environment. Human actions threaten the ecological balance. Colonizing new lands via the exploitation of uncultivated lands and protected areas and the overexploitation of soils favor the degradation of biological diversity. The problem of no access to electricity due to an urban crisis was caused by poor planning (Fagbedji 2018) and resulted from the production of urban space from below (Choplin 2013). In addition, some land disputes are related to double sales or the sale of properties that do not belong to the sellers. These disputes are the main reason for consulting a court in the region, and up to three land cases are tried or discussed each week at the town hall, according to an official. Noncompliance with the rules on the constitution of administrative reserves prevents the mayor’s office from providing urban facilities, because it does not have sufficient means to expropriate land in return for compensation (Sondou 2020). According to the planner at the town hall, because of the unavailability of a communal land register, houses are inhabited by unknown people, which is a disadvantage for land taxation. The city is experiencing increasing land speculation. As a traditional chief who has already sold several plots reports, “here each plot has its own price. We have no basis. Besides who can create it? It’s like I have my own shirt, I couldn’t sew it and want to sell it. If I want the money and you want the shirt, then let’s do business.” In this sense, only financial interest guides the operators, and without a human guide such as the traditional chief, the urban cacophony has only just begun in the town of Sotouboua. In addition to these problems, the town is unhealthy; the roads have no gutters, and the gullies create ponds in the courtyards of houses. The wastelands that foreigners created devalue the urban space. The traditional leaders do not cause the problems; however, given their role in land transmission, they become de facto actors in the negative transformations of the city.

Discussion

From the Law of July 24, 1906, to the recent adoption of the Law of June 14, 2018, on the land and property code in Togo, public policies aim to guarantee security and the right to property upstream and downstream to all citizens and to manage the city in the best possible way. This guarantee is influenced by various long procedures at the end of which a land title is issued to landowners or purchasers and registered in a land book at the Direction du Cadastre, de la Conservation Foncière et de l’Enregistrement (DCCFE). However, few people are willing to enter into this formal arcane, to follow all the steps of land acquisition in the cities, let alone in the second rank urban centers. Few heads are to be found (Takili 2014). In secondary areas, the predominance of ancestral acquisitions and the general modesty of building land transactions mean that the inhabitants have little interest in legal procedures (Nyalewo 2020). They prefer to take refuge in informal procedures that are quicker, simpler, and cheaper, especially since the majority of the population are, very often, of the same ethnic group and single descendants.

Despite the efforts made by governments through urban planning documents to control land, the results of the analysis of the field data show inherent deficiencies in the urban planning documents and the failure of their implementation. These remarks echo the observations made by Aholou and Sondou (2021) on institutional and bureaucratic weaknesses and exogenous shocks in the development of documents. “Land policy determines where and how future development will take place and, therefore, has a significant impact on housing supply and demand” (Shahab et al. 2021, p. 1,132). The demand for individual housing and the function of land as a savings asset (Degron 2012; Simmoneau 2017) will not cease; therefore, the actors must anticipate urban development. Sithou et al. (2018, p. 3) showed that

Sahelian populations, for example, have in the past put in place mechanisms for managing natural resources, including land, with the aim of preserving community heritage. The traditional institutions, personified by customary chiefs, guaranteed the respect of regulatory mechanisms that limited access to vital resources, in order to preserve them for the future of the group. Because of their sacred nature, respect for these rules was an absolute obligation for local populations and access to resources was the subject of mutual, respectful and profitable negotiations. Thus, there was consensus on agricultural and pastoral zones, agreements on the sharing of harvest residues, rules to be respected during hunting and fishing, rites related to the practice of bush fires, etc. In addition to these rules of access, there were also endogenous mechanisms for settling conflicts related to the use of land resources. These mechanisms made it possible to avoid the outbreak of violent conflicts and their negative repercussions on the integrity and sustainability of resources.

Traditional chieftaincy is the known form of administration in so-called Indigenous societies. It existed before colonization. History teaches us that the organization of societies depended on the authority of traditional leaders. The traditional chieftainship’s mission is to guarantee harmony between all inhabitants. It manages social conflicts and ensures the development and well-being of its subjects (Ayarma 2019, p. 87). Therefore, traditional leaders are the main respondents to their constituents. The chieftaincy has a mediating role in facilitating access to land and ensures that succession is carried out in accordance with the provisions and rules provided by custom.

Similar to the land ownership system in Ghana, in Togo, land ownership in the customary system begins at the level of the canton chiefs, who hold the title of supreme chief of customs and practices, followed by the lineage chiefs. These clan chiefs hold full customary ownership, and subjects hold usufruct or use rights. Unwritten customary law gives chiefs allodial rights to manage on behalf of their communities, and their subjects hold land use rights (Amanor 2008). Therefore, chiefs are trustees and managers of land on behalf of their communities (Asiama 2008). It is the responsibility of the state to exploit the adaptive and flexible features of customary land tenure to provide urban land for housing development (Akaateba 2019; Kidido and Biitir 2022). In addition, increasing efforts are being made to strengthen customary land management through institutional capacity building of customary land tenure institutions. The subdivision procedure begins with the initiation stage. In towns, particularly in Sotouboua, the chiefs of lineages, clans, or families hold full land ownership and initiate the subdivision operations in collaboration with the direct landowners who are invited to materialize their plot of land through parceling and demarcation without the prior opinion of the minister in charge of urban planning or the town hall.

However, for them to be used in urban planning, they must understand land control. As defined by Le Roy (1995), control is the exercise of power and authority that gives a particular responsibility to the person who, by an act of allocation of space, has reserved, more or less exclusively or absolutely, this space by favoring social negotiation instead of bureaucratic, fussy, interventionist, and capitalist regulations. In a study (Halpern et al. 2006) conducted in Oakland, California, US, the top-down model was applied; the decision was made in the center and could not be applied in the Oakland area, which caused disappointment. Another example is that during the implementation of urban planning documents in the city of Sotouboua, the surveyors interpreted the master plan’s map according to their thinking and parceled out the land differently. When developing the Plan d'Urbanisme de Détail, the voice of the public is very weak or nonexistent. By disconnecting the space for discussion from the space for decision, the master plan process does not allow for the evolution of urban planning practices, which inevitably leads to the disappointing results that were observed in this city. By concealing public participation, the plan no longer has public support and exacerbates the distrust of concessionaires to understand the merits of such a tool. As Bacqué and Gauthier (2011, p. 57) explain, “the mobilization of knowledge is seen as a means of controlling and organizing urban growth in a perspective of progress and of defining a project of general interest carried by the public authorities.”

If, for the state, the city is a product, for the citizen, it is a process. For the state, the city must meet certain standards and norms of urban planning. Urban planning is the projection on the ground of the values of a society. There is an anachronism between the cities that are produced by the state or that it wishes to produce through its urbanists and planners, and society. For the citizen, for whom the city is a process, the city is forged and built in a gradual and progressive manner. Each phase responds to certain values of the social stratum that conceives and inhabits it. As these social values change and evolve, the built environment follows the same changes and evolves concomitantly. The architectural evolution and the reason for living in Togolese cities and even in Sub-Saharan Africa demonstrates this logic of the city. Therefore, interventions in the city or its future must consider the aspirations of the inhabitants by involving them in the decision-making on the future of the city.

Therefore, an approach should emerge in which the actors, objectives, and needs of the local area are not ignored. This will be achieved through the intersection of the models mentioned previously. The units at the bottom-up level are well-informed on the sociological structure of the society. They have to set goals in accordance with the needs of society and transmit them to the center at the top-down level. Before moving on to the implementation phase, negotiations should occur between the central and local governments. It will be easier to implement public policies that are prepared with common ideas, impartially and completely according to the needs of the population. Each administrative actor can manage the process without adding interpretation because the decisions will be made jointly with the political actors responsible for policy-making and the implementation units. Therefore, traditional leaders should be trained with simplified planning schemes, and a grid for the recognition of transactions should be implemented, which allows them to follow and analyze the territorial changes they experience. The land tenure system in Togo, particularly the informal land transaction markets, benefits anyone who wants it; however, its functions remain imperfect. This is due to policy-induced land insecurity and the fragmentation of agricultural land. Therefore, the principle of collective ownership, where the elders and chiefs are entrusted with the land of their families, clans, and communities, is under siege (Yaro 2010), because customary land transactions have been transformed into an economic activity with unpredictable prerogatives on the part of chiefs, heads of families, clans, lineages, and private actors.

Conclusion

This study aimed to determine the role of traditional chieftaincy institutions in land transaction processes in Sotouboua, Togo. Substantial empirical evidence was gathered through interviews with chiefs, experts, and surveys of landowners. Interviews with chiefs, local communities, and experts in the field suggested that chiefs often go beyond their traditional role as custodians of the land to behave as land sellers, expropriators, negotiators, and conflict arbitrators (Gouamene et al. 2019; Yao et al. 2018). Colonial, imperial, and neoliberal forces have shaped the roles that chiefs currently play in land transactions; their actions could have profound effects on the morphology of the city and the social fabric of the community. Chiefs are supposed to act as custodians of the land and safeguard the interests of their communities; however, they are generally accustomed to acting as custodians of the land. Chiefs have become major actors in the informal management of land in Togo. The chiefs tend to justify their actions with their concerns to provide better development for their communities for access to land and housing. In addition, customary and popular provisions do not allow for the traceability of land data, which is a fortiori that is harmful to land and urban management. These situations are due to the weakness of the land administration system in Togo, which chiefs take undue advantage of to circumvent customary and statutory land laws. Understanding the true role of chiefs could have ramifications, because they are involved in a nonconstructive manner and, in some cases, their actions have catalyzed the nonimplementation of planning tools. All land transactions are subject to the scrutiny of traditional leaders, who become de facto intermediaries in land exchanges. In addition, their passivity originates from many irregular plots and land disputes in the cities. Therefore, the participatory approach, which is the official procedure for the realization of urban development projects, should be remodeled to involve the traditional leaders more in decision-making and even in conceptualization.

Finally, this study concluded that there is a need to move away from the current state of land transactions in Togo, which resembles a system of outright land sale without rules. The recent adoption of the land code and establishing a council of traditional chiefs is a good start; however, further formalization of the processes is needed. In addition, the role of chiefs must be clearly defined in the new urban planning code that is being developed, which includes explicit guidelines for their responsibilities in land management. In addition, the prospects for decentralization provide an opportunity to review the institutional arrangements for land tenure (Coulibaly 2006). The respective prerogatives of the state, local authorities and institutions (e.g., customary authorities and professional organizations) should be clarified and articulated for land management, which guarantees rights and conflict resolution. The realization of master plans should no longer be reserved for plan technicians and a few technocrats in the administration. The plans must be simplified to allow traditional leaders to understand better the routes and developments planned in the area. In addition, they must be accompanied by training and analysis grids for transforming space so that they can play their role fully as local development actors.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their positive comments. The second and third coauthors are listed alphabetically. The authors would like to thank the municipal and traditional authorities of Sotouboua, who kindly volunteered their time to be interviewed as part of this research. We also thank Kossi Komi, Estelle Chopkon, Koudjo Mario Degle, Esther Opara, and Pièrre Kitegi for reading and proofreading. This publication was funded by the Regional Center of Excellence on Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERViDA-DOUNEDON) at the University of Lomé, the African Universities Association, and the World Bank Group.

References

Adjei-Poku, B., S. K. Afrane, C. Amoako, and D. K. Inkoom. 2023. “Customary land ownership and land use change in Kumasi: An issue of chieftaincy sustenance?” Land Use Policy. 125: 106483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106483.

Adou, A. G., K. E. Yao, and D. C. Gouaméné. 2017. “Compétition pour l’occupation des bas-fonds dans les espaces urbains et péri-urbains à Daloa: Entre production vivrière et promotion immobilière.” Journal Africain de Communication Scientifique et Technologique 49: 6455–6476.

Ahmed, A., E. D. Kuusaana, and A. Gasparatos. 2018. “The role of chiefs in large-scale land acquisitions for jatropha production in Ghana: Insights from agrarian political economy.” Land Use Policy 75: 570–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.04.033.

Aholou, C. C., and T. Sondou. 2021. “Du processus d’élaboration à l’implémentation des outils de planification urbaine dans la ville de Sotouboua.” In TSE, Revue scientifique semestrielle, Territoires, sociétés, environnement, No 017, 120–134. Université de ZINDER, Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines.

Akaateba, M. A. 2019. “The politics of customary land rights transformation in peri-urban Ghana: Powers of exclusion in the era of land commodification.” Land Use Policy, 88: 1–10.

Alla, D. A. 1991, “Dynamisme de l'espace péri-urbain de Daloa, étude géographique.” Thèse de Doctorat 3ème cycle, département de géographie, Université d'Abidjan.

Amanor, K. 2008. “The changing face of customary tenure.” In Contesting land and custom in Ghana: State, chiefs and the citizen, edited by J. M. Ubink, and K. Amanor, 55–78. Leiden, Netherlands: Leiden University Press.

Antoni, J.-P., and S. Youssoufi. 2007. “Étalement urbain et consommation d’espace. Étude comparée de Besançon, Belfort et Montbéliard.” Revue Géographique de L’Est 47 (3): 1–16. http://rge.revues.org/1433.

Arthur, D. D., and T. D. Dawda. 2015. “Promoting rural development through chieftaincy institutions and district assemblies: Evidence from Sissala East District, Upper West Region of Ghana.” Ghana J. Dev. Stud. 12 (1–2): 164. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v12i1-2.10.

Asaaga, F. A. 2021. “Building on ‘traditional’ land dispute resolution mechanisms in rural Ghana: Adaptive or anachronistic?” Land 10 (2): 143–117. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10020143.

Asiama, S. O. 2008. “The concept of public land in Kumasi.” J. Ghana Instit. Surv. 1 (1): 44–50.

Augi. 2011. “Rapport d’étude de révision du Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme de Sotouboua (SDAU-Sotouboua).” Direction Générale de l'Urbanisme du Développement Municipal, de l'Habitat et du Patrimoine Immobilier (la DGUDMHPI).

Ayarma, A. 2019. L’insécurité foncière comme obstacle à l’équilibre de l’écosystème et au développement socio-économique de la préfecture du Zio au sud du TOGO, thèse unique en géographie. Lomé: Université de Lomé.

Bacqué, M. H., and M. Gauthier. 2011. “Participation, urbanisme et études urbaines. Quatre décennies de débats et d'expériences depuis «A ladder of citizen participation» de S. R. Arnstein.” Participations 1: 36–66. https://doi.org/10.3917/parti.001.0036.

Bertrand, F. 2004. Planification et développement durable, vers de nouvelles pratiques d’aménagement régionale. L’exemple de deux régions françaises: Le Nord-Pas-de-Calais et le Midi-Pyrénées. Tours: Thèse soutenue à l’université François Rabelais – Tours.

Bettalanffy, V. L. 1971. General system theory. New York: Allen Press.

Boateng, K., and S. Afranie. 2020. “Chieftaincy: An anachronistic institution within a democratic dispensation? The case of a traditional political system in Ghana.” Ghana J. Dev. Stud. 17 (1): 25–47. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v17i1.2.

Chenal, J. 2013. Modèles de planification de l’espace urbain. La ville ouest-africaine. Geneva: MétisPresse.

Chikaya-Banda, J., and D. Chilonga. 2021. “Key challenges to advancing land tenure security through land governance in Malawi: Impact of land reform processes on implementation efforts.” Land Use Policy 110 (June 2019): 104994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104994.

Choplin, A. 2013. “Chenal Jérôme, La ville ouest-africaine. Modèles de planification de l'espace urbain.” Métropoles 2013: 362. https://doi.org/10.4000/metropoles.5559.

Chorfi, K. 2019. “Le fait urbain en Algérie, de l'urbanisme d'extension à l'urbanisme de maitrise: l'urbanisme en discussion.” Thèse de Doctorat en sciences architecture, Institut d'Architecture et des Sciences de la Terre, Département d'Architecture, Université FERHAT Abbas de Sétif.

Cisse, Ch. 2018. En Afrique la ville est fabriquée en permanence par la planification et par l'informel. Afrique des Idées, Urbanisation informelle de l'Afrique: la planification et la pratique.

Cohen, B. 2004. “Urban growth in developing countries: A review of current trends and a caution regarding existing forecasts.” World Dev. 32 (1): 23–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.04.008.

Coulibaly, A., 2006. “Gestion des conflits fonciers dans le nord ivoirien, Droits, autorités et procédures de règlement des conflits.” Colloque international Les frontières de la question foncière At the frontier of land issues, 19. Montpellier, France: Colloque International.

Crook, T., J. Henneberry, and C. Whitehead. 2015. Planning gain: Providing infrastructure and affordable housing. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Davy, B. 2012. Land policy: Planning and the spatial consequences of property. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Degron, R. 2012. La France, bonne élève du développement durable? Paris: La Documentation Française.

Deville Ph. L., and A. Durant-Lasserve. 2008. Gouvernance foncière et sécurisation des droits dans les pays du Sud, Livre blanc des acteurs français de la Coopération, 127.

Dossou, G. O., and C. S. M. Dahande. 2014. “Contexte et développement de l’étalement urbain dans la commune de Bohicon.” Rev. Spec. J. Sci. FLASH 4 (9): 12.

Durand-Lasserve, A. 2004. La nouvelle coutume urbaine. Evolution comparée des filières coutumières de la gestion foncière urbaine dans les pays d’Afrique sub-saharienne; principaux résultats de la recherche et implications politiques. Paris: Note de recherche.

Enemark, S. 2010. “From Cadastre to land governance in support of the global agenda - The role of land professionals and FIG. Int. Federation Surveyors, 2010: 23.

Fagbedji, K. G. 2018. “Croissance urbaine et difficultés d’accès à l’électricité dans les espaces périurbaines de Lomé au Togo.” Thèse de doctorat en Unique de Géographie humaine, Département de Géographie, Univ. de Lomé.

Fox, S. 2012. “Urbanization as a global historical process: Theory and evidence from sub-Saharan Africa.” Popul. Dev. Rev. 38: 285–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00493.x.

Fuseini, I. 2016. Urban governance and spatial planning for sustainable urban development in Tamale, Ghana (Issue March). Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch Univ.

Gasparatos, A., G. P. von Maltitz, F. X. Johnson, L. Lee, M. Mathai, J. A. Puppim de Oliveira, and K. J. Willis. 2015. “Biofuels in sub-Sahara Africa: Drivers, impacts and priority policy areas.” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 45: 879–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.006.

Gouamene, D.-C., K. Tano, K. E. Yao, and K. L. Atta. 2019. “L’accès au foncier dans les espaces urbains et périurbains de Daloa (centre-ouest de la Côte d’Ivoire): Entre ordre et désordre.” In Les outils géographiques au service de l’émergence et du développement durable, Actes du colloque du 05 au 09 février 2018, 2ème partie, aménagement du territoire et développement durable, EDUCI, Coll, 287–300. Cocody, Abidjan: Sciences humaines.

Halpern, B. S., K. Kottenie, and B. R. Broitman. 2006. “ Strong Top-Down Control in Southern California Kelp Forest Ecosystems.” Science 312 (5777): 123–1232. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128613.

Hartmann, T., and B. Needham. 2012. “Introduction: Why reconsider planning by Law and property rights?” In Planning by law and property rights reconsidered, edited by T. Hartmann, and B. Needham, 1–22. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate.

Hartmann, T., and T. Spit. 2015. “Dilemmas of involvement in land management - comparing an active (Dutch) and a passive (German) approach.” Land Use Policy 42: 729–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.10.004.

Huang, X., H. Wang, and F. Fentao Xiao, 2012. “Simulating urban growth affected by national and regional land use policies: Case study from Wuhan, China.” Land Use Policy 112: 105850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105850.

INSEED-Togo (Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques et Démographiques). 2010. Quatrième recensement général de la population et de l'habitat – (RGPH4). Togo, Lomé: Bureau central du recensement.

Jacquemot, P. 2013. Economie politique de l’Afrique contemporaine, concepts, analyses, politiques. Paris: Armand Colin.

Kidido, J. K., and S. B. Biitir. 2022. “Customary succession and re-issuance of land documents in Ghana: Implications on peri-urban land developers in Kumasi.” Land Use Policy 120: 106270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106270.

Korbéogo, G. 2021. “Traditional authorities and spatial planning in urban Burkina Faso: Exploring the roles and land value capture by moose chieftaincies in Ouagadougou.” Afr. Stud. 80 (2): 190–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2021.1920365.

Le Roy, E. 1995. “La sécurité foncière dans un contexte africain de marchandisation imparfaite de la terre.” In Terre, terroir, territoire. Les tensions foncières, edited by C. Blanc-Pamard, and L. Cambrézy, 455–472. Dynamique des systèmes agraires. Paris: Éditions ORSTOM.

Liao, L. 2019. “L’émergence des élites techniciennes dans la planification participative à Zhuhai.” Revue Gouvernance 16 (2): 62–80. https://doi.org/10.7202/1066628ar.

Liu, Y., Y. Feng, Z. Zhao, Q. Zhang, and S. Su. 2016. “Socioeconomic drivers of forest loss and fragmentation: A comparison between different land use planning schemes and policy implications.” Land Use Policy 54: 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.01.016.

Lou, H. 2017. Fabriquer la ville avec les lotissements: Une qualification possible de la production ordinaire des espaces urbains contemporains? Histoire. Lyon: Université de Lyon; Université de Lausanne. Français. NNT : 2017LYSE2026ff. tel-01665105.

Lüdeke, M., P-H. Gerhard, and H-J. Schellnhuber. 2004. “Syndromes of global change: The first panoramic view.” Science Policy Making, GAIA 13 (1): 42–49. https://www.mkb-l.de/lit/gaia04.pdf.

Marrengane, N., L. Sawyer, and D. Tevera. 2021. “Traditional authorities in African cities: Setting the scene.” Afr. Stud. 80 (2): 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2021.1940098.

Ministère de l’urbanisme et de l’habitat, République Togolaise. 2010. Politique nationale de l’habitat et du développement urbain (PNHDU), Rapport final, 69.

Ndong, E. H. I. 2017. La participation citoyenne au processus d’élaboration des projets d’aménagement urbain au Sénégal. Renne: Mémoire de master Sciences de l’Homme et Société.

Nyalewo, M. K., K. M. Nassi, and G. Napo. 2022. “La gestion urbaine à l’épreuve de l’information sur les transactions foncières dans la ville du Moyen Mono 1 (TOGO).” AJLP&GS 5 (4): 783–798.

Nyalewo, K. M. H. V. 2020. Mécanismes d'information foncière et gestion urbaine du territoire communal de Moyen-Mono 1 (Togo), mémoire de master en Etudes Urbaines, Departement de Géographie, Université de Lomé.

Ouro-Djeri, A.-R., T. Atchou, and F. Tetteh. 2014. Plan de développement communal de Sotouboua 2015–2019 (PDC-Sotouboua 2015–2019). Rep. 116. Programme d’Appui à la Gouvernance Locale et à l’Intercommunalité dans la Région Centrale du TOGO, octobre 2014.

Ouedraogo, A. 2014. Démocratie et cheffocratie ou la quête d’une gouvernance apaisée au Faso, 278. Oralité et traditions, PUO, Ouagadougou.

Shahab, S., T. Hartmann, and A. Jonkman. 2021. “Strategies of municipal land policies: Housing development in Germany, Belgium, and Netherlands.” Eur. Plann. Stud. 29 (6): 1132–1150. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/09654313.2020.1817867.

Siiba, A., E. A. Adams, and P. B. Cobbinah. 2018. “Chieftaincy and sustainable urban land use planning in Yendi, Ghana: Towards congruence.” Cities 73: 96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.10.015.

Silva, C. N. 2012. “Research Methods for Urban Planning in the Digital Age.” Online Research Methods in Urban and Planning Studies: Design and Outcomes 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-0074-4.ch001.

Simard, M. 2014. “Étalement urbain, empreinte écologique et ville durable. Y a-t-il une solution de rechange à la densification?” Cahiers de Géographie du Québec 58 (165): 331–352. https://doi.org/10.7202/1033008ar.

Simmoneau, C. 2017. “Stratégies citadines d’accès au sol et réforme foncière au Bénin.” La pluralité comme enjeu?. http://www.metropolitiques.eu/Strategies-citadines-dd-acces-au.html.

Sithou, R. A.-M., A. B. Siddo, A. A. Hama, S. H. Abdoulzakou, A. M. Mahama, Y. A. O. Hassane, H. H. Yacouba, H. Sous la coordination de Moussa, and A. Manon. 2018. Gestion et prévention des conflits fonciers au Sahel, quel rôle pour les collectivités locales? Niamey, Niger: Comité National de Coordination des ONG sur la Désertification.

Sondou, T. 2020. Problématique d’opérationnalisation des outils de planification urbaine dans la ville de Sotouboua. Géographie, UL: Mémoire de Master en Etudes Urbaines.

Takili, M. 2014. “Croissance urbaine et dynamique des zones d’habitat précaire à Lomé.” Thèse de doctorat de Géographie Urbaine, Département de Géographie, Univ. de Lomé.