Previous studies have underlined the need for organizations to shift from a passive approach of valuing inclusion to taking steps to foster it. The following subsections discuss the critical gender-inclusion attributes for workers in construction sites.

Gender-Inclusion Attributes for Female Workers

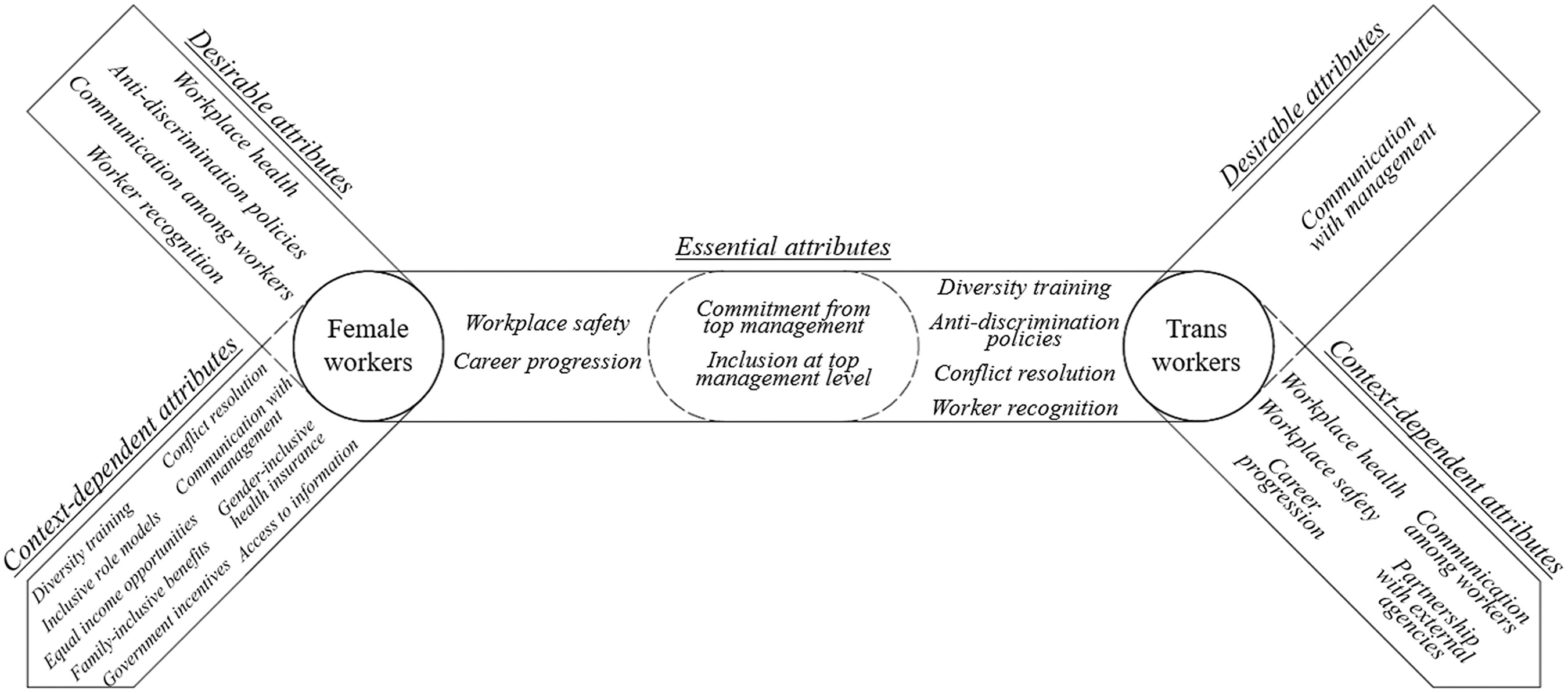

The essential gender-inclusion attribute is commitment from top management (A12), with a mean value of 3.613 (Table

3). This indicates that the level of gender inclusion at the site is directly influenced by the extent to which an organization’s top-level management is committed to the purpose. This is in the form of gender-inclusive policies, public statements, and decisions from the top management personnel, individually or collectively. The critical attributes identified as desirable and context-dependent may be deemed insignificant if the top management does not back them. Although workplaces may have a system to reflect gender inclusiveness, this does not necessarily translate into an inclusive environment unless the company’s executives openly and firmly support it. The top management has decision-making power and authority over the resources and thus drives the organization’s changes.

Inclusion at top management level (A22) is the following essential attribute with mean values of 3.631. The company leaders are the face of the organization and are the ones that directly or indirectly empower the workers. Hence, along with their commitment to fostering inclusion at lower levels, the top management should also ensure that diversity and inclusion are visibly practiced at their level (

Maurer et al. 2021); this can attract the entry of minority groups into the sector.

The next essential gender-inclusion attribute is workplace safety (A7), with a mean value of 3.565. Construction work exposes workers to many stressors that may undermine their physical and mental health (

Bridges et al. 2021). According to Turner et al. (

2021), the limited number of women workers in construction causes a cyclic effect that perpetuates onsite occupational health and safety barriers. Furthermore, women face hazards due to poor ergonomics and inappropriate apparel. Menches and Abraham (

2007) reported that most of the clothing, equipment, and tools required onsite are not designed for the women’s physique.

This discussion also holds good for the attribute of workplace health (A6), which was found to be a desirable attribute with a mean value of 3.505. The health and safety of workers is a human right, irrespective of demographic characteristics and occupation. Hence, appropriate health and safety measures should be implemented onsite that do not neglect the needs and issues of any particular gender of workers.

The other desirable attributes are antidiscrimination policies (A13) and worker recognition (A29), with mean values of 3.527 and 3.467, respectively. Discrimination, harassment, and marginalization have been long-standing barriers to inclusion, not only based on gender but other factors (

Bridges et al. 2021). Certain policies are required to keep such barriers in check at the site. Antidiscrimination policies should identify and address the various issues female workers face to prevent discrimination by their employers, coworkers, or other stakeholders. Moreover, Sabharwal (

2014) proposed that appreciating workers’ onsite efforts through official recognition fosters inclusion. This can be in bonuses, awards, or Employee of the Month titles. This can further improve career progression (A10), the final essential attribute with a mean value of 3.546. Maurer et al. (

2021) mentioned that a fair, transparent, and merit-based promotion opportunities are critical for retaining women in the construction workforce.

The findings also reveal that although communication with management (A19) and communication among workers (A20) are critical for gender inclusion, the latter is desirable whereas the former is context-dependent. A worker spends most of the time onsite with coworkers and subordinates rather than the top management. Workers should be encouraged to constantly communicate with each other, be it by passing on job-related information or talking about personal matters. This gradually leads to the formation of good relations at work and an inclusive workforce for new people joining it.

Furthermore, the lack of communication between workers and their employers leads to lower trust. This may lead to a feeling of unfair treatment among the workers and thus cause them to leave. Regular meetings should be arranged where workers can discuss issues and share feedback with their managers. Openness and communication are important aspects of inclusive culture in an organization because it facilitates knowledge sharing, conflict resolution, and coordination (

Duchek et al. 2020); bottom-up and horizontal communication is important to achieve this. Therefore, organizations should consider establishing channels at the site that enable both types of communication.

Additionally, communication is closely related to access to information (A17), a context-dependent attribute. The extent to which workers feel they are provided with the necessary resources to perform their role well, such as feedback, support and tools, varies from worker to worker. Much information is also shared informally through conversations, of which certain individuals may not be a part. Williams et al. (

2022) argued that the differences in accessing work-related information need to be eliminated.

Furthermore, equal income opportunities (A2) is highly discussed and addressed in the current global scenario, which may be why it is a context-dependent attribute. However, the literature suggests that gender pay disparities do exist. All workers should be paid based on their employment level and the number of hours worked rather than their gender identity; the basic wage criteria should remain the same for all. This finding is in line with Karakhan et al. (

2021), in which 10 indicators for achieving workforce inclusion in construction were identified, of which three were related to worker compensation: equitable pay at the industry level, equitable pay at the company level, and pay structure transparency. These were assessed to be highly influential concerning their impact on worker diversity and inclusion.

The other context-dependent attributes are family-inclusive benefits (A5), inclusive role models/supervisors (A8), diversity training of workers (A11), conflict resolution procedures (A18), gender-inclusive health insurance (A25), and government incentives (A27), which also need to be considered for making construction industry inclusive for women workers.

Gender-Inclusion Attributes for Trans Workers

Like the results found for women workers, the two attributes of commitment from top management and inclusion at top management level are essential attributes with mean values of 4.300 and 4.163, respectively, for trans workers. In addition to these two attributes, antidiscrimination policies, with a mean value of 4.374, are essential for trans workers’ inclusion. The lack of policies addressing discrimination toward trans workers can hinder their entry into the workforce. Construction sites can be intimidating for new trans workers, and their inclusion is also a unique experience for the existing workers. This may lead to discrimination toward trans workers at their early recruitment stages. For example, a transgender foreperson hired by a contractor to oversee a group of male workers may experience discriminatory behavior from some workers, making it challenging to work with them. In another situation, a transgender unskilled laborer may face harassment from a male supervisor.

This leads to the importance of the following attribute—diversity training of workers—which, although a context-dependent attribute for female workers, is essential for trans workers with a mean value of 4.123. All workers should be able to connect and work with each other freely while being aware of certain boundaries of trans people that need to be respected. The workers should be educated on the barriers preventing trans workers from entering the job. Periodic training sessions and awareness drives should be conducted on how to behave and coexist with trans coworkers onsite and beyond the site. Baboolall et al. (

2021) suggested that examples during diversity training of workers should include the negative experiences faced by trans workers at the site.

Moreover, the other essential attributes are conflict resolution procedures and worker recognition, with mean values of 4.211 and 4.126, respectively. Strategies should be devised to deal with conflict by understanding the perspectives of all people involved and resolving it so that it does not come up again. It is also important to recognize trans workers over time through official praise to establish them as a key part of the workforce so that other workers can appreciate their contribution. Here, the workers should indeed be singled out, not as a result of their gender but as a result of their contribution and efforts.

Communication with management is the only desirable attribute, and it goes hand in hand with the essential attributes. The context-dependent attributes are workplace safety, workplace health, career progression, and communication among workers because these become important after the initial obstacle of entering into a construction industry. The final context-dependent attribute unique to trans workers is partnership with external agencies (A23). Agreements between construction companies and institutions, such as nongovernmental organizations, civil societies, associations, and unions, can help minority groups access certain work positions and constantly monitor their progress. For example, the National Center for Transgender Equality is one such organization in the US. The Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment in India empowers transgender citizens through the Support for Marginalized Individuals for Livelihood and Enterprise (SMILE). The Tweet Foundation strives for skill-building and inclusive employment opportunities for trans people.

In India, transgender individuals have been long marginalized, struggling to access education and healthcare, or find decent work. On the other hand, there is increasing labor demand in the country due to its developing infrastructure. Although the solutions to both problems seem apparent, the social stigma surrounding the inclusion of trans workers is still prevalent. The findings of the present study can kindle the conversation around inclusion of trans workers and aid the government bridge this gap of unemployment and demand in the construction industry. By setting up the Transgender Persons Act, 2019 (

Bhattacharya et al. 2022), the government of India has taken the first step toward enhancing the inclusion of the trans population. The results herein and in future studies can be incorporated into the government’s efforts to further promote the diversity and inclusion of transgender individuals in construction and other sectors.