Disaster Education in the Context of Postsecondary Education: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

The upward tendency of global disasters and associated losses urgently calls for enhancing disaster education (DE) and professional training. Although postsecondary education institutions (PSEIs) play an essential role in this educational mission, a comprehensive understanding of DE development in PSEIs remains unclear. In response to this knowledge deficit, this article employed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) approach to explore the current development of DE in PSEIs through reviewing 76 publications from 2011 to 2022 through a mixed-method analysis process (univariate analysis and thematic inquiry). The quantitative analysis outcomes illustrate that the studies were unevenly distributed globally. The qualitative findings demonstrate the following fourfold characteristics of DE in PSEIs: (1) in terms of pedagogical characteristics of DE, there is a call for a radical shift in pedagogical strategies because the conventional teaching approaches are inadequate in tackling the potential risks and emerging hazards; (2) disciplinary and interdisciplinary perspectives have been integrated into DE, addressing diverse disasters and their differential influences; (3) through community-based partnerships, PSEIs can provide informal and nonformal education to affected individuals and communities; and (4) interconnections between DE and other educational approaches that broadly address global climate change have been recognized, contributing to resilience and sustainability. Based on these outcomes, this study recommends future DE-specific research could focus on (1) exploring potential radical pedagogical approaches to respond to emerging risks and hazards, (2) stimulating cross-disciplinary collaboration to address the full spectrum of disasters’ societal impacts, and (3) increasing collaboration between PSEIs and nonacademic organizations to raise grassroots awareness through informal DE.

Practical Applications

The increasing number of disasters worldwide encourages the development of DE, especially at PSEIs. A nuanced understanding of the DE development in PSEIs will identify the strengths and areas for improvement, better preparing future researchers, educators, practitioners, and policymakers. Having focused on DE at PSEIs, this literature review examined 76 journal articles published from 2011 to 2022. Disasters are a global issue, and the literature review outcomes show the uneven distribution of DE on a global scale. Although interdisciplinary approaches have been applied to DE in PSEIs to examine disaster’s diverse impacts, innovative pedagogies are needed to address the emerging issues associated with extreme events. DE provides community outreach activities to educate and support the individuals and communities hit by disasters. DE also joins other educational missions to contribute to the global issues of climate change, resilience, and sustainability. These findings suggest that future improvement could focus on developing novel pedagogies, enhancing cross-disciplinary collaboration, and promoting community outreach and public education.

Introduction

Disaster education (DE) is a functional, operational, and effective strategy for reducing disaster risk and developing capacity in current and prospective professionals as well as the general public (Breen et al. 2023; Preston 2021; Torani et al. 2019). It is essential for achieving disaster risk reduction (DRR) and building resilient and sustainable societies (Shaw et al. 2011b; Shiwaku and Shaw 2008). Disaster and emergency management (DEM) refers to systematic efforts to avoid and lessen the adverse effects of hazards by means of prevention, mitigation, and preparedness. In contrast, DRR goes beyond DEM and looks into the causal factors of disasters (UNISDR 2009). While often used interchangeably, DRR also refers to the policy objective of anticipating and reducing risk and DEM can be considered the execution of DRR because DEM involves actions on the ground (UNISDR 2015a).

In the context of postsecondary education, DE has been widely developed throughout traditional disciplines (such as engineering, planning, and public health) (Kitagawa 2021); DE-driven interdisciplinary programs and research centers have also been surfacing, such as the Interdisciplinary Disaster and Emergency Management Doctoral Program at the University of Delaware; the Master of Disaster and Emergency Management at York University, Canada; the Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University, Japan; and the University of Pretoria Natural Hazard Centre, South Africa. Evidence-based strategies suggest that DE builds specialists’ professional capacities and raises the general public’s awareness to better cope with and adapt to future disasters (Hoffmann and Blecha 2020; Rafliana 2012). As early as the 1980s and 1990s, Quarantelli (1988) and Mileti (1999) recognized the importance of education in disaster preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation. The exacerbation of climate change and the resulting increase in extreme events worldwide has propelled an urgent call to evaluate the existing DE to better educate prospective disaster and emergency management academics, practitioners, and policymakers (Subarno and Dewi 2022; Zhang and Wang 2022). The international DRR agreement has confirmed this need in the Sendai Framework of Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR 2015b), where DE becomes a cross-cutting theme covered by the four priority areas. This is the major thrust, encouraging a systematic review examining the existing DE knowledge, skills, and practices to identify future research, training, practice, and policy- and decision-making orientations.

Two main streams of scholarship have primarily contributed to the understanding and development of DE. First, scholars in the field of hazards and disaster research have highlighted the forms, functions, and roles of education in DRR and DEM (Shaw et al. 2011b; Subarno and Dewi 2022) that can be further divided into two fields: (1) scholars who are engaged in their disciplinary silos, including sociology, social work, architecture, and engineering (Adams et al. 2022; Cooper and Briggs 2014; Perdomo and Pando 2014), and (2) scholars who are contributing from an inter/transdisciplinary orientation (Chan and Nagatomo 2022; Righi et al. 2021; Tidball et al. 2010). The second stream essentially comprises the work of education scholars who have contributed to pedagogical innovations by bringing in social justice and antiracist perspectives and emphasizing equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in the teaching and learning of DE (Dufty 2020; Preston 2010, 2021). However, several potential grounds for cross-fertilization can significantly enhance our understanding of DE, including the pedagogical aspect of teaching and learning in DE. This article considers the work of both streams concerned with postsecondary-level DE.

DE can be conducted in diverse forms but is primarily conducted in three streams: formal, nonformal, and informal (Shaw et al. 2011b). Formal education, offered by traditional education institutions (i.e., K–12, colleges, and universities), is organized programs recognized as qualified with structured learning objectives and goals (Kitagawa 2021; Thayaparan et al. 2014). Generally, universities and colleges offer formal education and train next-generation academics and practitioners (Littledyke et al. 2013). Postsecondary education, in this article, refers to formal education after secondary (Grade 12) education, including, but not limited to, apprenticeship; certificate and diploma from colleges and technical institutes; and bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees from colleges, universities, and research institutions (Statistics Canada 2023). The term postsecondary education is often used interchangeably with tertiary education, implying any form of postsecondary formal education as indicated (World Bank 2021). Educational institutions that offer postsecondary education are referred to in this article as postsecondary education institutes (PSEIs).

Nonformal and informal DE are less structured and more flexible than formal education. They are usually conducted in the form of seminars, workshops, and short courses, which may or may not lead to certification (Subarno and Dewi 2022; Shaw et al. 2011b). Informal education often involves community participation, engaging the general public to develop their capacity. Although universities and colleges are primarily considered formal educational hubs, they also contribute to nonformal and informal DRR and DEM in the form of community-based outreach activities (i.e., workshops and seminars) in collaboration with public, private, and not-for-profit sectors (Brundiers 2018). DE addressed in this article primarily focuses on postsecondary institutions and their roles in formal, nonformal, and informal education.

DRR-specific postsecondary education is essential for knowledge, skills, and capacity development and enhancement for hazard and disaster professionals and stakeholders from other related fields (Littledyke et al. 2013). PSEIs are also engaged in research and collaboration with other postsecondary and research institutions and communities. Such partnerships are required to address emerging disaster risks induced by climate change at the local level and improve the course and program curriculum (Wongphyat and Tanaka 2020; Yasuhiro et al. 2019). However, a holistic understanding of the diverse roles of PSEIs in DE still needs to be explored. Responsively, this article aims to narrow this knowledge deficit by systematically reviewing material from the last decade (2011–2022) and developing recommendations that will inform future research.

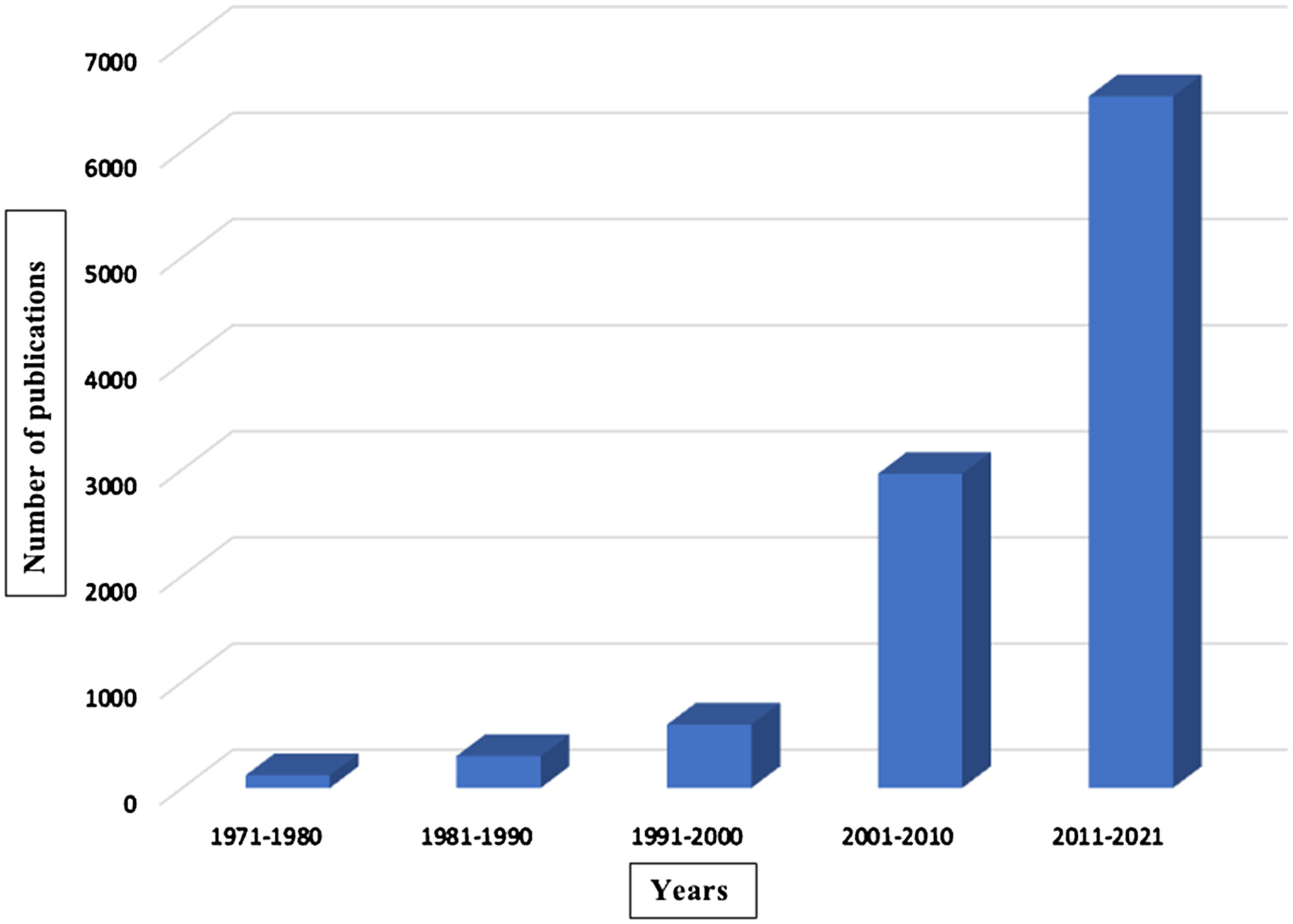

Two factors justify the review period. First, DE literature has exponentially increased since 2011. For instance, a search using the keyword “disaster education” in the SCOPUS database shows an exponential growth in literature (Fig. 1). Second, some of the foundational and comprehensive works emerged during 2011, including the book Disaster Education by Shaw et al. (2011b).

To synthesize the current state of knowledge on DE in PSEIs, this literature review is guided by the following research questions: (1) How has education on risk and disaster, DRR, and DEM been framed at the PSEIs? (2) What roles do PSEIs play in nonformal and informal DE? (3) How does the current literature connect DE with other global issues, such as climate change? and (4) What gaps need to be addressed and what are other recommendations for future research? To answer these questions, this article employed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) approach (Moher et al. 2009; Page et al. 2021).

Methods

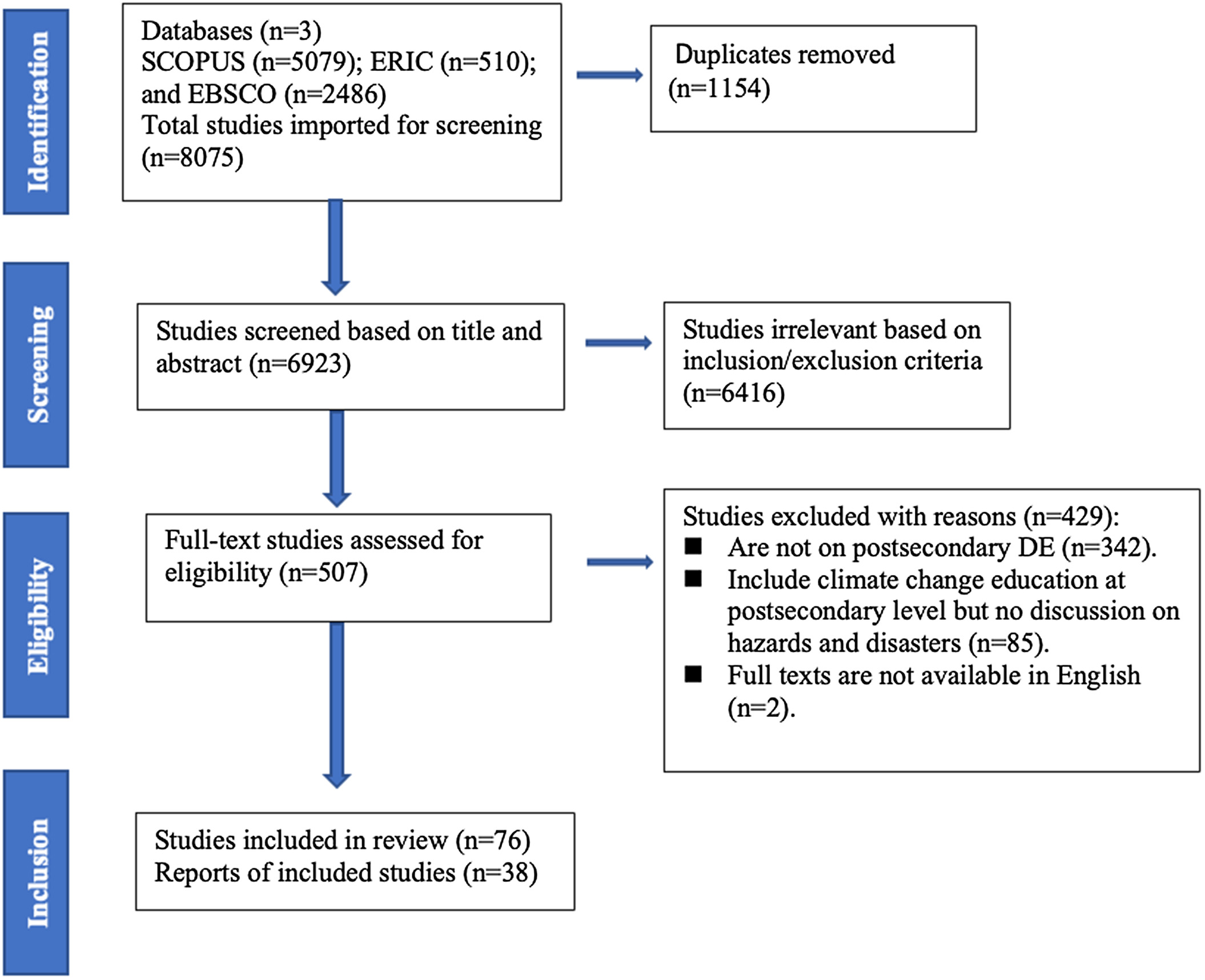

The PRISMA approach, a widely accepted guide for systematic review, was used to direct the data curation of this literature review (Fig. 2). A mixed-method analysis process, that is, quantitative (univariate analysis) and qualitative (thematic inquiry) analyses, was utilized to develop the findings to address the research questions.

Databases and Searching Keywords

Three multidisciplinary publication databases (SCOPUS, EBSCO interface, and ERIC) were selected. ERIC is an education research–specific database (Falagas et al. 2008; Hertzberg and Rudner 1999). Two major groups of keywords were derived according to the research questions: Group 1: hazards and disasters (i.e., Hazar* OR risk* OR “climate change” OR Disaster*) AND Group 2: postsecondary education (i.e., university* OR college* OR postsecondary OR education). Two filters were chosen to narrow the search boundary, years of publication (January 2011 to April 2022) and languages (English). The initial search in the three databases yielded 8,075 publications, which were imported into Covidence, a web-based virtual tool to facilitate different steps in systematic review. Covidence automatically removed 1,154 duplicates, and 6,923 publications moved to the next step.

Data Screening and Extraction

Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts of the 6,923 publications through the following criteria to evaluate the publications’ relevance:

•

Does the document include education for risk, hazard, and DEM or mitigation?

•

Does the document highlight the roles and activities of PSEIs in promoting education for risk, hazard, and DEM?

Any differences were reviewed by a third scholar with expertise in DEM. A total of 6,416 irrelevant publications were removed, and the remaining 507 were moved to full-text evaluation. As shown in Fig. 2, 429 documents were evaluated and withdrawn because (1) documents are not on postsecondary DE (), (2) documents include climate change education at the postsecondary level but no discussion on risk and disaster (), and (3) full texts are not available in English (). Finally, 76 documents remained for extraction and analysis (Choudhury and Wu 2022).

Data Analysis

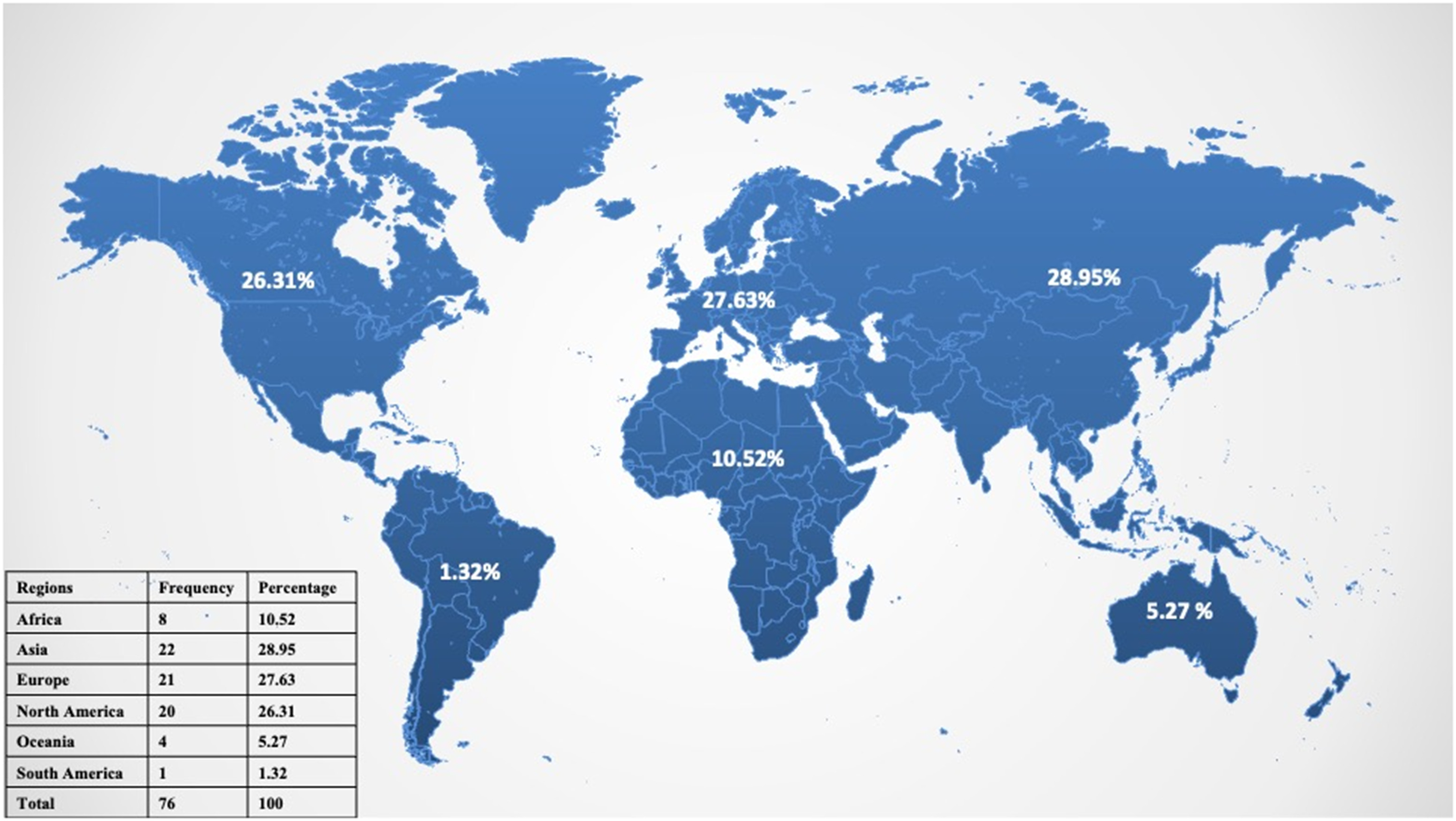

A mixed-method approach was used to analyze the 76 documents. A quantitative metadata analysis was conducted to uncover the geographical coverage of the selected content and nature of the study (i.e., empirical or review study). Mapping geographical location helps understand the spatial distribution and variation of DE-related content and the underlying causes of such variation. Guided by the research questions, two authors conducted a qualitative thematic analysis, focusing on the primary findings of the 76 publications (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane 2006). They individually coded the publications through an inductive approach and collaboratively developed the primary four themes (Thomas 2006), namely, (1) the pedagogical characteristics of DE, (2) the nature of disciplinary and interdisciplinary DE, (3) the role of universities in informal and nonformal education, and (4) connection of DE with other global agendas, such as climate change. Using these four themes as a framework, they reviewed their codes again, and the most typical codes are presented.

Results

This section has two broad parts. The first provides a quantitative analysis in terms of the general overview of the selected content, including the geographical distribution of the selected content and the nature of the content (i.e., case study or review). The second provides findings from the thematic analysis and has four main subsections as identified previously.

General Overview of Selected Content

Geographical Coverage of the Selected Content

Fig. 3 provides an overview of the geographical distribution of studies—regions where studies were conducted and/or hosted. For example, the case study conducted by Huston and Ebers (2020) was focused on North America (specifically the United States), while Brundiers (2018) is a review article that was hosted in North America (specifically the United States). It was found that the most significant number of studies were conducted or sponsored in Asia (28.95%), closely followed by Europe (27.63%) and North America (26.31%). These three regions combine to cover 82.89% of all studies. It prompts the question: does such geographical distribution of selected content relate to the number of disasters in these regions? It was observed that Asia experienced 40.74% of the total global disasters from 2010 to 2022 (Table 1). It can be assumed that in the case of Asia, such a high percentage of disasters might have triggered the greatest number of DE-related content in Asia. However, such an assertion does not hold valid for other regions. For example, Europe and North America had experienced only 11.31% and 12.62% of the total global disasters, respectively, from 2010 to 2022 (Table 1), but 27.63% and 26.31% of the entire selected DE-related content was either conducted or hosted in Europe and North America, respectively. Moreover, Africa experienced the second-highest number of total disasters, but only 10.52% of selected content was found to be hosted and/or conducted in Africa. This variation may have other explanations, such as the number of scholars engaged in disaster-related research and programs at the postsecondary level, the amount of research funding in disasters, and national financial investment in PSEIs.

| Continent | Number of disaster events | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 1,664 | 23.79 |

| Asia | 2,850 | 40.74 |

| Europe | 791 | 11.31 |

| North America | 883 | 12.62 |

| Oceania | 196 | 2.81 |

| South America | 611 | 8.73 |

| Total | 6,995 | 100.00 |

Source: Data from EM-DAT (2022).

Nature of the Study

Of the 76 selected documents, the highest number of documents () was perspective/opinion/synthesis/report, which was 47.37% of the total studies. A total of 34 studies are empirical studies, accounting for 44.73% of the total studies. Authors adopted qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods in the cases of empirical studies. Evaluation was the least number of studies among the selected content (Table 2).

| Nature of the study | Types of empirical study | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical study | Qualitative | 13 | 17.10 | 44.73 |

| Quantitative | 08 | 10.53 | ||

| Mixed | 13 | 17.10 | ||

| Perspective/opinion/synthesis/report | 36 | 47.37 | ||

| Evaluation | 6 | 7.90 | ||

| Total | 76 | 100 | ||

It is evident from the preceding bibliometric discussion that content is not symmetrically distributed, in terms of regions and the nature of studies. However, to understand the major themes that run through the texts, it is necessary to understand current research themes and future research directions. Such themes help answer the research questions mentioned previously and unpack current trends, debates, and gaps in DE-related research. The following section elaborates on the four key themes from the content analysis.

Thematic Analysis

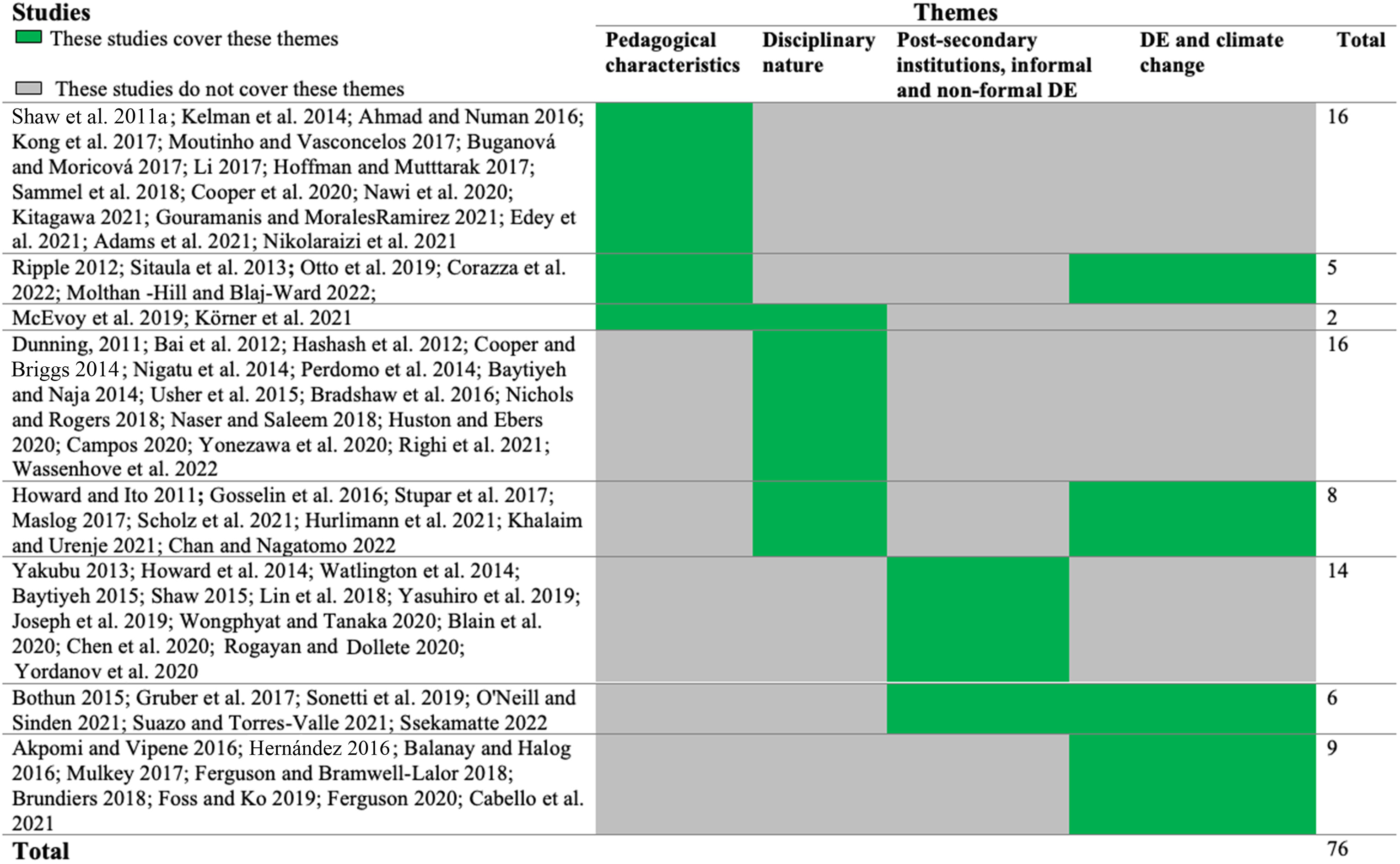

This section provides an overview of the thematic analysis of all selected content (). Fig. 4 indicates the chronological order of publications and the specific number of documents across specific and overlapping themes. The four major themes cover most of the content () while overlapping themes cover 21 documents. The pedagogical characteristics and disciplinary nature themes have the highest number of documents, with 16 each. The postsecondary institutions, informal and nonformal DE theme contains the second most significant number of documents (), and the DE and climate change theme contains the least (). The four themes appear in varying chronological order, with content related to the pedagogical characteristics and disciplinary nature themes emerging prior to (i.e., 2011) content related to the postsecondary institutions, informal and nonformal DE theme (i.e., 2013) or the DE and climate change theme (i.e., 2016). The following section elaborates on the four major themes, drawing reports from 38 studies that are deemed most relevant.

Pedagogical Characteristics of DE

In terms of pedagogical characteristics of DE in formal learning environments, this review found a demand for a pedagogical tool for DE at the postsecondary level. Gouramanis and MoralesRamirez (2021) argue that the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction can be used as a pedagogical approach to developing a new pedagogical tool for DE. These authors demonstrate that the four priority areas of action outlined in the Sendai Framework can be used to create pedagogical principles. They applied these principles in a third-year undergraduate-level course on natural hazards in the Department of Geography at the National University of Singapore, where students from other departments, such as engineering, participated. This course had four learning objectives aligned with the four priority areas of the Sendai Framework. PSEIs can design future courses and programs using this study as a model that treats the Sendai Framework as a tool to derive pedagogical principles.

The urgency in developing new or radical pedagogical tools has been recognized by many who point to the inadequacy of conventional teaching approaches to tackle emerging risks induced by climate change and DEM, and in an attempt to address this need, Kong et al. (2017) coined the term “pedagogical riskology”—introducing a risk-oriented learning approach. Alternatively, Corazza et al. (2022) argued for a radical shift in existing pedagogies to meet sustainable development goals (SDGs), drawing insights from Jack Mezirow’s transformative learning theory and Freire’s theory of critical pedagogy. In their study, they compared a control group provided a traditional course from previous years with an experimental group provided with education for sustainable development material, finding that students from the experimental group developed research and career interests in sustainability. In addition, Molthan-Hill and Blaj-Ward (2022) called for redesigning university learning to tackle the challenge of climate change. They proposed five practice models to educate climate leaders at universities and posited that a pedagogical intervention was required for a lasting impact on education. Other approaches for DE at the postsecondary level have included (1) using “mental model-based learning” (Moutinho and Vasconcelos 2017), and (2) integrating teaching and learning with action research (McEvoy et al. 2019). These studies both demonstrate the need for risk-informed pedagogical tools that differ from conventional pedagogical tools and provide examples of how radical shifts in pedagogy for DE can be achieved.

As opposed to specific pedagogical tools and approaches, Shaw et al. (2011b) provided five guiding principles of postsecondary education in DRR. The first principle, inclusive curriculum, evaluates different types of hazards and their intensity, frequency, perception, loss and damage, recovery, prevention, and mitigation in combination with socioeconomic conditions, technical capacities, and political priorities. The second principle, theoretical focus, considers the basic concepts and theories in the field of DRR, including climate change adaptation and global warming. The third principle is field orientation, which implies connecting classroom education with real-life experience in the form of research (Wu et al. 2022a). The fourth principle, the interdisciplinary approach, recognizes that disaster preparedness and management cannot be limited by disciplinary boundaries. The final principle, skill enhancement—producing a skilled workforce to meet market demand—relates to innovation in DE to promote continuing education, as called for by Buganová and Moricová (2017).

The essential takeaway is that although there are multiple ways a pedagogical shift can be attained, further evaluation of pedagogical approaches is urgently needed to choose the most effective pedagogy. Moreover, a combination of multiple approaches, such as combining the Sendai Framework with Jack Mezirow’s theory of transformative learning and Freire’s theory of critical pedagogy, may prove most fruitful.

Disciplinary Nature of DE

Disaster is a multifaceted phenomenon with disciplinary knowledge contributing in various ways to manage disaster and mitigate risk (McEntire and Smith 2007). In this review, a discussion on DE from the disciplinary perspective is directed toward finding pathways to integrate risk and disaster-related education into respective disciplines to better manage disasters on the ground and mitigate the impacts of shock. Table 3 provides an overview of how different authors have attempted integrating DE into their discipline.

| Discipline | Key observation | Authors | Study context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Consideration of long-term disaster recovery and response into landscape architecture design | Nichols and Rogers (2018) | Oceania |

| Veterinary | The need for formal training for veterinarians | Huston and Ebers (2020); D. Dunning, “Preparedness and disaster response training for veterianary students: A model for academic change through partnership, collaboration, and innovation,” Unpublished thesis, 2011 | North America |

| Journalism | Formal courses on environmental journalism for journalism students so they understand the underlying causes of disaster and do not only report on disaster loss and damage | Maslog (2017) | Asia |

| Nursing | Building nurses’ capacity in emergency and disaster preparedness and management | Usher et al. (2015) | Asia |

| Social work | Three potential areas were identified: (1) curriculum development, (2) experiential learning, and (3) simulations | Cooper and Briggs (2014) | Oceania |

| Urban planning | Incorporating specialized and crosscutting courses both at graduate and undergraduate levels | Scholz et al. (2021); Hurlimann et al. (2021) | Oceania |

| Agrometeorology | Natural hazard analysis and management into agrometeorology | Nigatu et al. (2014) | Africa |

| Engineering | Use of information technology in engineering education for natural hazard risk management | Perdomo and Pando (2014) | South America |

| Health and dental | Dental hygienists have a role to play in DM; more formal training for dental hygienists in postdisaster response and management | Naser and Saleem (2018); Bradshaw et al. (2016) | Asia and North America |

The role of urban planning, for example, in risk and DEM in built environments, has been widely recognized (Park et al. 2021; Zhou et al. 2022). Scholz et al. (2021) analyzed 1,196 courses from universities in sub-Saharan English-speaking African and Southeast Asian countries. They found that courses on climate change and DEM are mainly missing from urban planning programs in those regions. As a consequence, students lack understanding concerning the vulnerability of different social groups, resulting in a lack of consideration of risk in planning. Scholz et al. (2021) proposed three options for making urban planning program risk and disaster informed: (1) incorporating new specialized courses on the social dimension of disaster and risk reduction, such as on poverty and gender; (2) adding specialized programs on crosscutting themes, such as climate change, disaster, and gender at the graduate level; and (3) adding specific mandatory courses at both undergraduate and graduate levels.

Cooper and Briggs (2014) asked whether we need specific DEM education for social work. Recognizing the critical role played by social workers in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery, these authors identified a lack of professional training for social workers in Australia. Three potential areas were identified: (1) curriculum development, (2) experiential learning, and (3) simulations. In terms of curriculum, they found that content containing legal aspects and interagency and personal relationship management—critical for on-the-ground DEM—were missing. As for experiential learning, students must gain first-hand experience working with organizations that handle DEM, such as the Red Cross, to understand the organization’s services and operational features—also known as service learning. Last, simulation is achieved by having students role-play different hypothetical disaster scenarios, encouraging them to apprehend the needs and challenges present in a real-life context.

Professionals in veterinary science also recognize the role of DE. For example, Huston and Ebers (2020) point out that there is an expectation among community residents on the Mississippi Gulf Coast of veterinarians that they are involved in DEM to some degree. However, veterinarians are often ill-prepared for such expectations. They surveyed 706 veterinary practitioners to assess their knowledge, training, and planning for DEM. They found that only 20% of the respondents had formal training on DEM. They concluded that providing formal disaster training to veterinarians would increase overall disaster preparedness in the community.

The preceding examples demonstrate how DE can be integrated into different disciplines, with each discipline making a unique contribution to DDR. In addition to such disciplinary attempts to incorporate DE, there are other ways DE can be furthered to address the multidimensionality of disaster. One such strategy is to take an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary perspective to address a specific hazard or all hazards. Such attempts recognize that disaster is a complex, multiscalar, and multileveled problem that requires going beyond disciplinary boundaries. For instance, Righi et al. (2021) documented the interconnectedness of different types of hazards (i.e., natural, technological, and biological disasters), asserting that DRR would require a holistic approach. Hence, interdisciplinary training and education—for example, at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy, the Academic Upgrading Course on Territorial, Environmental and Health Emergencies (EmTASK) is required for DRR. Others support the establishment of an interdisciplinary connection of education with other disciplines (Wu and Hou 2019). For instance, Campos (2020) attempted to establish an interdisciplinary connection between architecture and education in pursuing DRR.

While Righi et al.’s (2021) approach applies to all hazards, Hashash et al. (2012) documented a multidisciplinary course for a specific earthquake hazard. The structure of an interdisciplinary graduate course on earthquake loss assessment and mitigation was outlined, integrating engineering, social sciences, and information technology. The goal of the course was to unpack the source of a hazard using state-of-art engineering techniques and information technologies to mitigate impacts and encourage positive societal consequences.

DE is disciplinary and interdisciplinary, spanning both specific and all hazards. In this review, most of the disciplinary discussion on DE has been concerned with the broader sense of DRR rather than any particular hazard. In contrast, discussion on interdisciplinary DE has been linked to both specific and all hazards. As such, there is a need for more research on the connection between disciplinary DE and specific hazards.

Postsecondary Institutions, Informal and Nonformal DE

As previously discussed, DE involves formal, nonformal, and informal education and training (Shaw et al. 2011b; Subarno and Dewi 2022). PSEIs, such as universities and colleges, through engagement and partnership with communities can provide informal and nonformal education to people in the community who bear the brunt of disasters. Engagement between PSEIs and communities likely has a two-way benefit: (1) community capacity and awareness building through extension programs, and (2) improvement of the curriculum at the postsecondary level to address local needs and challenges (Baytiyeh 2015; Joseph et al. 2019).

Rogayan and Dollete (2020) surveyed 480 residents in five southern municipalities of Zambales, Philippines. The survey sought to acquire baseline information on the community’s preparedness and awareness of tsunamis and storm surges for the purpose of (1) facilitating the incorporation of DEM-specific topics into the course curriculum at the basic and advanced levels, and (2) developing customized community extension programs that meet the community’s needs, raising awareness and preparedness.

Another case study that provides evidence of universities’ leadership in nonformal and informal education is the study conducted by Joseph et al. (2019) on volcanic hazards in Sulphur Springs Park, Saint Lucia, in the Lesser Antilles. This study took a citizen science approach—a participatory approach requiring collaboration and partnership with local stakeholders and community residents (Groulx et al. 2017; Ruiz-Mallén et al. 2016). The project significantly increased the awareness of citizen scientists through the use of a poster on volcanic hazards that raised public awareness by sharing scientific findings concerning volcanic hazards. Similarly, Baytiyeh (2015) documented universities’ potential role in effective earthquake risk reduction in Lebanon through formal, informal, and nonformal education. Universities can provide formal training to community and student volunteers and provide nonformal and informal initiatives, including community engagement, awareness campaigns, and volunteer programs.

PSEIs can establish partnerships and collaborations among themselves and with research institutions and management agencies to offer nonformal and informal DE at the community level. For example, the Virgin Islands Territorial Emergency Management Agency (VITEMA), the University of the Virgin Islands, and the Caribbean Ocean Observing System carry out a collaborative effort that provides information about risk of coastal hazards (i.e., tsunami and storm surge) and enhances community preparedness in the US Virgin Islands (Watlington et al. 2014).

Alternatively, PSEIs can contribute to nonformal and informal education by offering online courses (Cooper et al. 2020; Edey et al. 2021). For example, Kelman et al. (2014) proposed a web-based tool called Spare-Time University (STU) that provides disaster-related knowledge in lay language to anyone with access to the internet. The creators envisioned a wide range of beneficiaries, including farmers, small vendors, and even medical scientists. In addition, the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado Boulder developed a series of online training modules to enhance the diverse capacities of hazards and disaster students, early career researchers, and practitioners (Adams et al. 2022; Peek et al. 2020b). These online courses complement existing strategies and are designed based on current knowledge of disasters without any need for a radical pedagogical shift.

Thus, PSEIs can offer informal and nonformal DE in a range of methods, from partnerships and collaborations with research institutions and the community to online education, bolstering formal DE at the postsecondary level. Such partnerships among PSEIs, practitioners, and the community can enhance the feedback among different forms of DE, i.e., providing informal and nonformal education to community awareness building and revising and upgrading course curricula based on local needs and challenges.

DE and Climate Change

The inextricable linkage among disaster, climate change, and sustainability is surfacing in recent years (Kelman 2017; Uitto and Shaw 2016). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2022) recently noted the connection between climate change and disaster risk, further emphasizing the urgent need to better link climate change and DE in educational programs. As such, there will be a deficiency in DE at the postsecondary level without considering sustainability and climate change–related issues. It leads to the question: how does DE fit into sustainability education and climate change education? Sustainability education (SE) is often used interchangeably with other similar concepts, such as education for sustainable development and sustainable development education (UNESCO 2014). The following section provides a few examples of how such connections are demonstrated in the literature.

Brundiers (2018) attempted to build connections between DE and SE, putting forth that current educational programs on disaster and sustainability fail to develop skillsets for practitioners, educators, and community residents to capture the postdisaster opportunity for transformative change required the attainment of greater sustainability. This is mainly due to the lack of mutual interaction and collaboration among fields. Brundiers (2018) identified five areas of complementarity between SE and DE. First, SE primarily prepares students for normal time; consequently, there needs to raise awareness of sustainability or sustainable recovery in the field of DE. This leads to the second aspect: sustainability is the blind spot for DE, while disaster recovery is the blind spot for sustainability. Third, learning outcomes for sustainability are the development of various competencies, while dealing with emergency and disaster risk are the learning outcomes for DE.

Regarding the pedagogical aspect, both fields focus on experiential learning through collaboration with community dwellers and practitioners. Last, both deal with pragmatic issues, such as risk and resources. Considering these five areas of convergence between DE and SE, five integrated sets of competencies were identified that are needed for postdisaster sustainability: (1) system thinking, (2) futures thinking, (3) values thinking, (4) strategic thinking, and (5) interpersonal thinking.

Ferguson and Bramwell-Lalor (2018) attempted to build connections between climate change education and sustainable development education. They documented that climate change education includes DRR and DE. They provided guidelines and examples of how climate change education and sustainable development education can be integrated into the curriculum at the postsecondary level. First, new courses that combine climate change education and sustainable development education can be integrated into existing degree programs. They provided the example that an environmental education course that addressed climate change education and sustainable development education was merged into an existing program in the School of Education of the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus in Jamaica. This course was designed considering the local environmental context of the Caribbean region. Second, new postgraduate programs can be developed apart from individual courses. For example, a new postgraduate degree program was designed with specific goals and objectives, where students were offered choices from a range of alternative courses depending on their interests. However, a core course for this program was Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction Education, where basic concepts and theories related to climate change and their connection with sustainable development were introduced with special reference to the local context. While designing these courses and postgraduate programs, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO’s) document on education for sustainable development, particularly from four main areas, such as learning content, pedagogy and learning environments, learning outcomes, and social transformation, was consulted. Also, local and regional stakeholders were consulted.

The preceding sections elaborated on the four major qualitative themes. Each theme elaborates on the four distinct areas of DE at the postsecondary level, and each theme attempts to answer different research questions mentioned in the “Introduction” section. These themes are also interconnected. The following “Discussion and Conclusion” section elaborates and summarizes the findings and areas of future research.

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize the current state of knowledge on DE at the postsecondary level. To this end, the preceding sections attempted to answer the following questions through quantitative univariate and qualitative thematic analysis:

•

How have education on risk and disaster, DRR, and DEM been framed at PSEIs?

•

What are the roles PSEIs play in nonformal and informal DE?

•

How does the current literature connect DE with other global issues, such as climate change?

This section summarizes key findings and attempts to answer the final research question: what are the gaps and recommendations for future research?

In terms of quantitative findings, this article documented the geographic distribution of DE-related content and the nature of the studies (i.e., empirical study, course evaluation, or perspective/synthesis). In terms of the former, it was found that studies were not symmetrically distributed around the globe. Most studies were conducted in Asia, followed by Europe and North America. This article also attempted to find the connection between the frequency of disasters and the number of DE-related documents for a particular region. It was found that such links only hold for the continent of Asia, where the highest number of DE-related content was found along with the highest frequency of disasters. The second and third highest number of DE-related content was located in Europe and North America, respectively, but with relatively less frequent disaster events than in Asia and Africa during the same period (2010–2022). The continent of Africa ranked second in terms of the frequency of disaster events and fourth in terms of DE-related content. In terms of the nature of the study, this article found three categories of studies: perspective/opinion/synthesis/report, empirical study, and evaluation. The first covers the highest number of documents, closely followed by empirical research, while evaluation had the smallest number of studies in the selected content.

In terms of qualitative findings, this study documents four major themes: (1) the pedagogical characteristics of DE; (2) the disciplinary nature of DE; (3) postsecondary institutions, informal and nonformal DE; and (4) DE and climate change. The first two themes provide answers to the first research question, while the third and fourth themes offer answers to the second and third research questions, respectively. Regarding the pedagogical characteristics of DE, there is a call for a radical shift in tools and approaches, recognizing that conventional teaching approaches are inadequate in tackling the emerging risks induced by climate change. Different recommendations have been put forward that include using the Sendai Framework for disaster risk reduction as a new pedagogical tool for DE (Gouramanis and MoralesRamirez 2021; Drolet et al. 2015), as well as drawing insights from Jack Mezirow’s theory of transformative learning and Freire’s theory of critical pedagogy (Corazza et al. 2022). Different disciplines, such as architecture, social work, and urban planning, have been found to integrate risk and disaster-related education into respective disciplines for better managing disasters on the ground and mitigating the impact of shocks (Wu 2021a, b). In addition to such disciplinary attempts to incorporate DE, attempts have been made to integrate DE into an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary perspective to address a specific hazard or all hazards (Peek et al. 2020a). PSEIs, such as universities and colleges, through engagement and partnership with communities can provide informal and nonformal education to community inhabitants who bear the brunt of disasters. Last, attempts have been made to connect DE and climate change education. A greater synergy among these three streams is more likely to foster the skill sets of practitioners, educators, and community residents to capture the postdisaster opportunity for transformative change required to attain greater sustainability. This takes us to the discussion of interthematic connection.

For furthering DE at the postsecondary level, the interconnection among the four themes must be considered. For example, Shaw et al. (2011b) provided five guiding principles of higher education in DRR: inclusive curriculum, theoretical focus, field orientation, interdisciplinary approach, and skill enhancement. To implement such principles, PSEIs need to build partnerships with community-based and different research institutions and promote interdisciplinary DE. As noted previously, such engagement of PSEIs with communities is likely to have a two-way benefit: (1) increasing community capacity and awareness through extension programs, and (2) improvement of the curriculum at the postsecondary level. However, such feedback relationships among different forms of DE are still a significant gap in DE that requires further attention.

Last, decades of disaster studies’ scholarship indicate that often informal DE through means of partnership has taken the top-down approach where community voice, learning, and knowledge are relegated to a more marginalized position, which is likely to make a community more vulnerable than resilient in the long term (Choudhury and Wu, forthcoming; Choudhury et al. 2021; Grove 2013; Wu 2021a). The recent decolonization turn in disaster studies recognizes the need to incorporate more community voices, learning, and knowledge to bring about DRR and resilience (Cadag 2022; Siddiqi and Canuday 2018). Similarly, education scholars urge a socially just form of DE where equity and justice rank high in importance, particularly valuing different worldviews and ontological and epistemological positions (Dufty 2020; Preston 2012). It is also recognized that greater integration of different forms of learning, knowledge, and worldviews can significantly enhance the next generation of scholars’ diverse capacities to achieve DRR (Wu et al. 2022b). This article contends that equity, diversity, and inclusion are vital in offering different forms of DE, which is still a significant gap in DE in general, and at the postsecondary education level in particular. To this end, a cross-fertilization between these two streams of scholarship is required.

Data Availability Statement

All data used to develop this literature review are available in a repository online in accordance with funder data retention policies (https://doi.org/10.17603/ds2-4z53-ay44).

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported by the Canada Research Chairs Program (Grant No. CRC-2020-00128). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Canada Research Chairs Program.

References

Adams, R. M., C. Evans, A. Wolkin, T. Thomas, and L. Peek. 2022. “Social vulnerability and disasters: Development and evaluation of a converge training module for researchers and practitioners.” Disaster Prev. Manage. Int. J. 31 (6): 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-04-2021-0131.

Baytiyeh, H. 2015. “Developing effective earthquake risk reduction strategies: The potential role of academic institutions in Lebanon.” Prospects 45 (2): 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-015-9344-3.

Bradshaw, B. T., A. P. Bruhn, T. L. Newcomb, B. D. Giles, and K. Simms. 2016. “Disaster preparedness and response: A survey of U.S. dental hygienists.” J. Dent. Hyg. 90 (5): 313–322.

Breen, K., M. Greig, and H. Wu. 2023. “Learning green social work in global disaster contexts: A case study approach.” Soc. Sci. 12 (5): 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050288.

Brundiers, K. 2018. “Educating for post-disaster sustainability efforts.” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 27 (Oct): 406–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.11.002.

Buganová, K., and V. Moricová. 2017. “Innovation of education in risk and crisis management.” Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 16 (Nov): 177–182.

Cadag, J. R. 2022. “Decolonising disasters.” Disasters 46 (4): 1121–1126. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12550.

Campos, P. 2020. “Resilience, education and architecture: The proactive and ‘educational’ dimensions of the spaces of formation.” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 43 (Apr): 101391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101391.

Chan, M. N., and D. Nagatomo. 2022. “Study of STEM for sustainability in design education: Framework for student learning and outcomes with design for a disaster project.” Sustainability 14 (1): 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010312.

Choudhury, M., and H. Wu. Forthcoming. “Learning capacity and diversification, enabling and constraining factors, and external assistance: A cross-national comparative analysis of long-term livelihood recovery.” Int. J. Mass Emerging Disasters.

Choudhury, M., and H. Wu. 2022. “Disaster education and postsecondary educational institutes: A systematic literature review.” DesignSafe. CI. https://doi.org/10.17603/ds2-4z53-ay44 v1.

Choudhury, M.-U.-I., C. E. Haque, A. Nishat, and S. Byrne. 2021. “Social learning for building community resilience to cyclones: Role of indigenous and local knowledge, power, and institutions in coastal Bangladesh.” Ecol. Soc. 26 (1): 5. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12107-260105.

Cooper, L., and L. Briggs. 2014. “Do we need specific disaster management education for social work?” Aust. J. Emerging Manage. 29 (4): 38–42.

Cooper, V. A., G. Forino, S. Kanjanabootra, and J. von Meding. 2020. “Leveraging the community of inquiry framework to support web-based simulations in disaster studies.” Internet High Educ. 47 (June): 100757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2020.100757.

Corazza, L., D. Cottafava, and D. Torchia. 2022. “Education for sustainable development: A critical reflexive discourse on a transformative learning activity for business students.” Environ. Dev. Sustainability 2022 (Apr): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02335-1.

Drolet, J., H. Wu, M. Taylor, and A. Dennehy. 2015. “Social work and sustainable social development: Teaching and learning strategies for ‘green social work’ curriculum.” Soc. Work Educ.: Int. J. 34 (5): 528–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1065808.

Dufty, N. 2020. Disaster education, communication and engagement. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Edey, D., C. M. Thompson, J. Cherian, and T. Hammond. 2021. “Online local natural hazards education for young adults: Assessing program efficacy and changes in risk perception for Texas natural hazards.” J. Geogr. High Educ. 46 (3): 447–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2021.1947204.

EM-DAT (Emergency Events Database). 2022. “The international disaster database.” Accessed June 12, 2022. https://www.emdat.be.

Falagas, M. E., E. I. Pitsouni, G. A. Malietzis, and G. Pappas. 2008. “Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses.” FASEB J. 22 (2): 338–342. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF.

Fereday, J., and E. Muir-Cochrane. 2006. “Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development.” Int. J. Qual. Methods 5 (1): 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107.

Ferguson, T., and S. Bramwell-Lalor. 2018. “Tertiary-level sustainability and climate change education: Curricula development efforts for Caribbean teachers.” Caribb. Q. 64 (1): 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/00086495.2018.1435337.

Gouramanis, C., and C. A. MoralesRamirez. 2021. “Deep understanding of natural hazards based on the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction in a higher education geography module in Singapore.” Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 30 (1): 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2020.1751391.

Groulx, M., M. C. Brisbois, C. J. Lemieux, A. Winegardner, and L. A. Fishback. 2017. “A role for nature-based citizen science in promoting individual and collective climate change action? A systematic review of learning outcomes.” Sci. Commun. 39 (1): 45–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547016688324.

Grove, K. 2013. “Hidden transcripts of resilience: Power and politics in Jamaican disaster management.” Resilience 1 (3): 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2013.825463.

Hashash, Y. M. A., A. Mwafy, A. S. Elnashai, and J. F. Hajjar. 2012. “Development of a multidisciplinary graduate course on consequence-based earthquake risk management.” Int. J. Continuing Eng. Educ. Life Long Learn. 22 (1–2): 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJCEELL.2012.047039.

Hertzberg, S., and L. Rudner. 1999. “The quality of researchers’ searches of the ERIC database.” Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 7 (25): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v7n25.1999.

Hoffmann, R., and D. Blecha. 2020. “Education and disaster vulnerability in Southeast Asia: Evidence and policy implications.” Sustainability 12 (4): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041401.

Hurlimann, A., P. B. Cobbinah, J. Bush, and A. March. 2021. “Is climate change in the curriculum? An analysis of Australian urban planning degrees.” Environ. Educ. Res. 27 (7): 970–991. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1836132.

Huston, C. L., and K. L. Ebers. 2020. “Assessing disaster preparedness and educational needs of private veterinary practitioners in Mississippi.” J. Vet. Med. Educ. 47 (2): 230–238. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.0618-074r.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2022. “Summary for policymakers.” In Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by H.-O. Pörtner, 3–33. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Joseph, E. P., V. B. Jackson, D. M. Beckles, L. Cox, and S. Edwards. 2019. “A citizen science approach for monitoring volcanic emissions and promoting volcanic hazard awareness at Sulphur Springs, Saint Lucia in the Lesser Antilles Arc.” J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 369 (Jan): 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2018.11.005.

Kelman, I. 2017. “Linking disaster risk reduction, climate change, and the sustainable development goals.” Disaster Prev. Manage. Int. J. 26 (3): 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-02-2017-0043.

Kelman, I., M. Petal, and M. H. Glantz. 2014. “Using a spare-time university for disaster risk reduction education.” In Learning and calamities: Practices, interpretations, patterns, edited by H. Egner, M. Schorch, and M. Voss, 125–178. London: Routledge.

Kitagawa, K. 2021. “Conceptualising ‘disaster education’.” Educ. Sci. 11 (5): 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050233.

Kong, Y., L. R. Kayumova, and V. G. Zakirova. 2017. “Simulation technologies in preparing teachers to deal with risks.” Eurasian J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 13 (8): 4753–4763. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00962a.

Littledyke, M., E. Manolas, and R. A. Littledyke. 2013. “A systems approach to education for sustainability in higher education.” Int. J. Sustainable High Educ. 14 (4): 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-01-2012-0011.

Maslog, C. 2017. “Asian journalism education and key challenges of climate change: A preliminary study.” Pac. J. Rev. 23 (1): 32–42.

McEntire, D. A., and S. Smith. 2007. “Making sense of consilience: Reviewing the findings and relationship among disciplines, disasters and emergency management.” In Disciplines, disasters and emergency management: The convergence and divergence of concepts, issues and trends in the research literature, edited by D. A. McEntire, 320–336. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publishing.

McEvoy, D., U. Iyer-Raniga, S. Ho, D. Mitchell, V. Jegatheesan, and N. Brown. 2019. “Integrating teaching and learning with inter-disciplinary action research in support of climate resilient urban development.” Sustainability 11 (23): 6701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236701.

Mileti, D. 1999. Disasters by design: A reassessment of natural hazards in the United States. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press.

Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, and D. G. Altman. 2009. “Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement.” J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62 (10): 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005.

Molthan-Hill, P., and L. Blaj-Ward. 2022. “Assessing climate solutions and taking climate leadership: How can universities prepare their students for challenging times?” Teach. High Educ. 27 (7): 943–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2022.2034782.

Moutinho, S., and C. Vasconcelos. 2017. “Model-based learning applied to natural hazards.” J. Sci. Educ. 18 (2): 47–50.

Naser, W. N., and H. B. Saleem. 2018. “Emergency and disaster management training; knowledge and attitude of Yemeni health professionals- a cross-sectional study.” BMC Emerg. Med. 18 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-018-0174-5.

Nichols, T., and R. Judy. 2018. “Sustainability’ after disaster: Confronting the complexities of recovery in the field: An educational experience.” In Sustainable development research in the Asia-Pacific region, edited by W. L. Filho, J. Rogers, and U. Iyer-Raniga, 221–233. Berlin: Springer.

Nigatu, L., B. Shimeles, and K. Kibret. 2014. “Implementation and accomplishment of the MSc agrometeorology and natural risk management program at Harmaya University, Ethiopia.” In Proc., Fourth RUFORUM Biennial Regional Conf., 177–183. Maputo, Mozambique.

Page, M. J., et al. 2021. “The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews.” BMJ 372 (Jan): 71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Park, K., H. Oh, and J. H. Won. 2021. “Analysis of disaster resilience of urban planning facilities on urban flooding vulnerability.” Environ. Eng. Res. 26 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4491/eer.2019.529.

Peek, L., H. Champeau, J. Austin, M. Mathews, and H. Wu. 2020a. “What methods do social scientists use to study disasters? An analysis of the social science extreme events research network.” Am. Behav. Sci. 64 (8): 1066–1094. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220938105.

Peek, L., J. Tobin, R. Adams, H. Wu, and M. Mathew. 2020b. “A framework for convergence research in the hazards and disaster field: The natural hazards engineering research infrastructure converge facility.” Front. Built Environ. 6 (Jul): 110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2020.00110.

Perdomo, J. L., and M. A. Pando. 2014. “Using information technology to incorporate natural hazards and mitigation strategies in the civil engineering curriculum.” J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 140 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EI.1943-5541.0000175.

Preston, J. 2010. “Prosthetic white hyper-masculinities and ‘disaster education’.” Ethnicities 10 (3): 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796810372299.

Preston, J. 2012. Disaster education: “Race”, equity and pedagogy. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Preston, J. 2021. “Disaster education.” In Vol. 3 of Encyclopedia of Marxism and Education, 203–216. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publisher.

Quarantelli, E. L. 1988. “Disaster education: Its substantive content and the target audiences.” Accessed July 14, 2022. http://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/503.

Rafliana, I. 2012. “Disaster education in Indonesia: Learning how it works from six years of experience after Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004.” J. Disaster Res. 7 (1): 83–91. https://doi.org/10.20965/jdr.2012.p0083.

Righi, E., P. Lauriola, A. Ghinoi, E. Giovannetti, and M. Soldati. 2021. “Disaster risk reduction and interdisciplinary education and training.” Prog. Disaster Sci. 10 (Apr): 100165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2021.100165.

Rogayan, D. V., and L. F. Dollete. 2020. “Disaster awareness and preparedness of barrio community in Zambales, Philippines: Creating a baseline for curricular integration and extension program.” Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. 10 (2): 92–114. https://doi.org/10.33403/rigeo.634564.

Ruiz-Mallén, I., L. Riboli-Sasco, C. Ribrault, M. Heras, D. Laguna, and L. Perié. 2016. “Citizen science: Toward transformative learning.” Sci. Commun. 38 (4): 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547016642241.

Scholz, W., T. Stober, and H. Sassen. 2021. “Are urban planning schools in the global south prepared for current challenges of climate change and disaster risks?” Sustainability 13 (3): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031064.

SCOPUS. 2022. “Search for an author profile.” Accessed August 12, 2022. https://www.scopus.com/freelookup/form/author.uri.

Shaw, R., F. Mallick, and Y. Takeuchi. 2011a. “Essentials of higher education in disaster risk reduction: Prospects and challenges.” In Disaster education, edited by R. Shaw, K. Shiwaku, and Y. Bingley, 95–114. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

Shaw, R., Y. Takeuchi, Q. R. Gwee, and K. Shiwaku. 2011b. “Disaster education: An introduction.” In Disaster education, edited by R. Shaw, K. Shiwaku, and Y. Bingley, 1–22. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

Shiwaku, K., and R. Shaw. 2008. “Proactive co-learning: A new paradigm in disaster education.” Disaster Prev. Manage. Int. J. 17 (2): 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560810872497.

Siddiqi, A., and J. J. P. Canuday. 2018. “Stories from the frontlines: Decolonising social contracts for disasters.” Disasters 42 (Oct): 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12308.

Statistics Canada. 2023. “Education, training and learning.” Accessed March 4, 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/subjects/education_training_and_learning/postsecondary_education.

Subarno, A., and A. S. Dewi. 2022. “A systematic review of the shape of disaster education.” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 986 (1): 012011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/986/1/012011.

Thayaparan, M., C. Malalgoda, K. Keraminiyage, and D. Amaratunga. 2014. “Disaster management education through higher education—Industry collaboration in the built environment.” Procedia Econ. Financ. 18 (Sep): 651–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00987-3.

Thomas, D. R. 2006. “A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data.” Am. J. Eval. 27 (2): 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748.

Tidball, K. G., M. E. Krasny, E. Svendsen, L. Campbell, and K. Helphand. 2010. “Stewardship, learning, and memory in disaster resilience.” Environ. Educ. Res. 16 (5–6): 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2010.505437.

Torani, S., P. M. Majd, S. S. Maroufi, M. Dowlati, and R. A. Sheikhi. 2019. “The importance of education on disasters and emergencies: A review article.” J. Educ. Health Promot. 8 (Apr): 85. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_262_18.

Uitto, J. I., and R. Shaw, eds. 2016. “Sustainable development and disaster risk reduction: Introduction.” In Sustainable development and disaster risk reduction, 1–12. Berlin: Springer.

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). 2014. “Education for sustainable development.” Accessed March 5, 2023. https://www.unesco.org/en/education/sustainable-development.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2009. “2009 UNISDR terminology on disaster risk reduction.” Accessed March 5, 2023. https://www.preventionweb.net/files/7817_UNISDRTerminologyEnglish.pdf.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2015a. “Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction 2015.” Accessed March 5, 2023. https://www.undrr.org/publication/global-assessment-report-disaster-risk-reduction-2015.

UNISDR (United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction). 2015b. “Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030.” Accessed June 23, 2022. https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf.

Usher, K., M. L. Redman-MacLaren, J. Mills, C. West, E. Casella, E. D. Hapsari, S. Bonita, R. Rosaldo, A. K. Liswar, Y. Zang. 2015. “Strengthening and preparing: Enhancing nursing research for disaster management.” Nurse Educ. Pract. 15 (1): 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2014.03.006.

Watlington, R. A., E. Lewis, and D. Drost. 2014. “Coordinated management of coastal hazard awareness and preparedness in the USVI.” Adv. Geosci. 38 (Apr): 31–42. https://doi.org/10.5194/adgeo-38-31-2014.

Wongphyat, W., and M. Tanaka. 2020. “A prospect of disaster education and community development in Thailand: Learning from Japan.” Nakhara J. Environ. Des. Plann. 19 (Dec): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.54028/nj202019124.

World Bank. 2021. “Understanding poverty.” Accessed March 3, 2023. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/tertiaryeducation.

Wu, H. 2021a. “Bottom-up adaptive social protection: A case study of grassroots self-reconstruction efforts in post-Wenchuan earthquake rural reconstruction and recovery.” Int. J. Mass Emerging Disasters 39 (1): 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072702103900104.

Wu, H. 2021b. “Integration of the disaster component into social work curriculum: Teaching undergraduate social work research methods course during COVID-19.” Br. J. Soc. Work 51 (5): 1799–1819. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab110.

Wu, H., and C. Hou. 2019. “Utilizing co-design approach to identify various stakeholders’ roles in the protection of intangible place-making heritage: The case of Guchengping Village.” Disaster Prev. Manage.: Int. J. 29 (1): 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-09-2018-0291.

Wu, H., J. Karabanow, and T. Hoddinott. 2022a. “Building emergency response capacity: Social workers’ engagement in supporting homeless communities during COVID-19 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (19): 12713. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912713.

Wu, H., L. Peek, M. C. Mathews, and N. Mattson. 2022b. “Cultural competence for hazards and disaster researchers: Framework and training module.” Nat. Hazard. Rev. 23 (1): 06021005. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000536.

Yasuhiro, S., et al. 2019. “Enhancing citizens’ disaster resilience through an international transdisciplinary research project in Mongolia.” Geogr. Rev. Jpn. Ser. B 92 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4157/geogrevjapanb.92.1.

Zhang, M., and J. Wang. 2022. “Trend analysis of global disaster education research based on scientific knowledge graphs.” Sustainability 14 (3): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031492.

Zhou, Y., F. Du, K. Xiong, W. Li, and X. Zou. 2022. “The development of rural residents’ sense of place in an ecological restoration area: A case study from Huajiang Gorge, China.” Mt. Res. Dev. 42 (1): 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-21-00013.1.

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

Copyright

This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

History

Received: Oct 15, 2022

Accepted: Apr 3, 2023

Published online: Jun 5, 2023

Published in print: Aug 1, 2023

Discussion open until: Nov 5, 2023

ASCE Technical Topics:

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Download citation

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.