Paving the Way for Progress: A Systematic Literature Review on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in the AEC Industry

Publication: Journal of Management in Engineering

Volume 40, Issue 3

Abstract

The importance of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry has become increasingly salient as the industry continues to struggle with recruitment and retention of high-quality talent throughout construction organizations in the US. The existing literature has explored the barriers faced by various groups who are underrepresented in the construction industry; however, the research is fragmented and lacks a set of synthetic conclusions to drive future work. To this end, we performed a systematic literature review (SLR) to analyze the existing literature, which has categorized the barriers contributing to underrepresentation of women, ethnic minorities, individuals with disabilities, individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ), and individuals who have been previously incarcerated. As a result of the SLR, 10 influential variable clusters affecting the recruitment and retention of underrepresented groups were identified, including (1) organizational aspects, (2) work environment, (3) work–life balance, (4) individual or project performance, (5) education, (6) health, (7) safety, (8) wage gap, (9) communication, and (10) ethics. Our findings lead to suggestions for further research, including a need to identify best practices based on empirical evidence from within the range of current DEI practices that have been investigated by prior research. Our results can benefit practitioners, legislators, employers, and others working to improve DEI in the construction industry.

Introduction

Increasing construction workforce diversity, both in craft and staff roles, is vital to addressing the ongoing workforce shortage (Sunindijo and Kamardeen 2017). Diversity is realized in various forms and applies to various groups (Loosemore and Lim 2016) based on gender, race, or ethnicity but also age, sexual orientation, and ability (Bailey et al. 2022). Across national contexts, data suggest that the construction industry exhibits low levels of diversity. Data retrieved from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics confirmed the low levels of participation by women and other underrepresented groups in construction based on race and ethnicity (US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2023). The statistical data show that women form 9.8% of total construction employees. The share of US construction industry employees is 7.9% for Black or African Americans, 2.1% for Puerto Ricans, 27.8% for Mexicans, 1.1% for Cubans, and 1% for Asians (US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2023).

The latest national statistics of the US demonstrate that women make up 50.4% of the total population. Hispanics account for 19.1%, Black or African Americans 13.6%, and Asians 6.3% (US Census Bureau 2022). Comparing the workforce data with national demographic statistics showed that certain groups are significantly underrepresented in the construction industry. For instance, although women make up 50.4% of the total US population, they constitute only 9.8% of total construction employees, highlighting a substantial gender disparity in the industry. Although, at first glance, Hispanics appear to be overrepresented in the construction industry, their representation in managerial positions is relatively low (Saseendran et al. 2020).

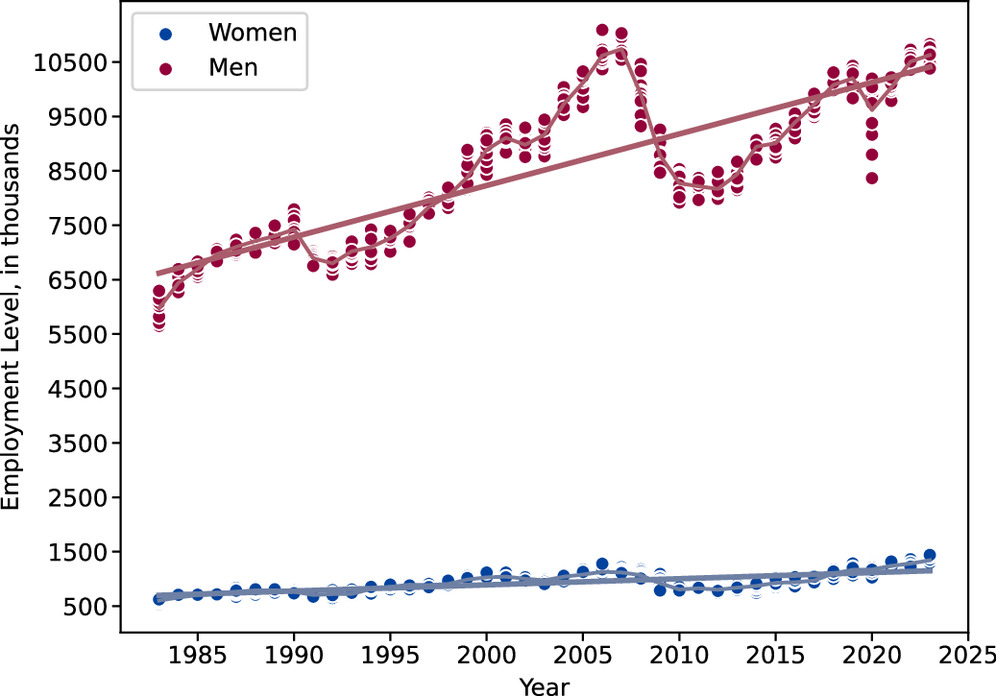

Although the diversity numbers cannot be the sole indicator of the workplace inclusivity level (Powell and Sang 2013), they can provide an overview of the industry’s performance over time. Fig. 1 depicts the quarterly data on the number of female employees in the US construction industry (US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2023). The employment level of women has shown a slight increasing trend with fluctuations. This chart displays the fluctuations in the number of women in the construction industry over time. For example, there seems to have been a decrease in the participation of women in the industry centered around 1991 and 2001. These fluctuations raise questions about the potential contributing factors. Considering the economic context, the fluctuations coincide with periods of economic uncertainty and workforce shifts. These speculations justifies further investigations and can offer valuable insights. For example, could factors impacting this decrease have helped to predict the decrease in 2010, which coincided with the economic downturn during the Great Recession? Furthermore, studying diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) provides the answers to the underlying reasons for women’s low participation and retention in the construction industry.

Official statistics from various countries highlight the global underrepresentation of women in construction. For example, in Australia, women comprise 18.5% of the construction workforce (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022), whereas in China, their representation stands at 14% (China National Bureau of Statistics 2018). In the UK, women make up 15.8% of the construction labor (UK Office for National Statistics 2023), and in Sweden, the figure is 11.3% (Statistics Sweden 2023).

Given the aging of the global construction workforce and the subsequent labor shortage (Hasan et al. 2021), women and other underrepresented groups are largely untapped labor pools. Given the construction industry’s vital socioeconomic role, there is an urgent need for a larger and more diverse workforce. However, efforts to recruit a more diverse workforce are wasted without effort to retain that workforce, in part, through equitable and inclusive policies, practices, procedures, and programs.

Previous studies that have examined issues related to DEI in construction can be broadly categorized into two groups: (1) studies investigating the entry barriers, challenges, and enablers for various diverse groups considering their common and distinct characteristics, and (2) those analyzing retention rates of workers and professionals, with a particular focus on women in AEC. Careful consideration is necessary before implementing pro-DEI initiatives at any level, from the project to national top-down approaches or legislation, to avoid potential negative consequences (English and Bowen 2012). For example, implementing a plan to hire more women without careful consideration of qualifications and competencies may lead to negative perceptions among coworkers and hinder progress toward genuine inclusivity. Additionally, if new hires are not adequately qualified, it could reinforce stereotypes and create hesitation from management to support future DEI initiatives.

Existing literature reviews on DEI in architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) are limited in focus to specific underrepresented groups such as workers with disabilities (Roelofs et al. 2011) and women (Hasan et al. 2021; Naoum et al. 2020), but no cross-cutting, comprehensive and synthetic review exists that treats DEI as the central focus of inquiry. As a result of this gap, we know that, e.g., site safety may be a barrier to entry for women in construction, but we may not how this barrier relates to individuals with disabilities. Do common barriers exist for different underrepresented groups and if so, can common approaches to removing the barriers be developed?

The objective of this systematic literature review (SLR) is to address the multifaceted issue of DEI in AEC by reviewing a comprehensive set of academic publications from 2010. Through systematic analysis, this paper dynamically characterizes DEI groups (e.g., different genders or races) and explores their specific domains (e.g., construction or architecture) and parameters (e.g., safety or performance). By clustering the identified barriers, gathering the suggested solutions, exploring research gaps, and outlining future research, this study provides recommendations for researchers and practitioners.

Background

The concept of diversity has been a focal point for researchers studying a variety of groups in AEC. For instance, Martins et al. (2011) noted a lack of diversity in considering women, ethnic and racial minorities, and people with disabilities in constructing the facilities for the 2012 Olympic games. Karakhan et al. (2021) focused on evaluation of DEI at the workforce level of the construction industry, but results were limited to gender and ethnicity. Consequently, other forms of diversity (e.g., age or ability) were not considered. As these examples demonstrate, previous research on DEI in AEC has been limited to focus on specific groups, which impedes creation of a sustainable and inclusive workforce (Karakhan et al. 2023). Conducting a comprehensive review of these groups can help explore potential intersections that are vital for understanding the potential dynamics between their characteristics. In other words, deeper knowledge about the needs and impacts of each group can help with proposing tailored practices respecting each individual.

The construction industry is currently undergoing a process of institutional change, with social value increasingly competing with cost and quality as a measure of overall project success (Troje and Kadefors 2018). Recognizing the importance of various DEI groups and social procurement concepts can have practical implications for educational institutions, individual practitioners, and organizations (Keku et al. 2021).

Although an increasing focus has been given to DEI in construction, the previous reviews are not without limitations. An in-depth analysis of the literature revealed a number of potential areas of enhancement in the existing literature reviews on the topic. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on individual parameters, potentially limiting the inclusivity of findings, this review paper has an extensive scope. Furthermore, the previous literature reviews relied on papers published before 2010, which also reduces the generalization capacity to the current situation (Naoum et al. 2020).

As for the more recent reviews, Tijani et al. (2022) systematically reviewed work–life balance in the construction industry, identifying it as one of the important parameters concerning the mental health of workers and improving DEI in the sector. Within a similar scope, Rotimi et al. (2022) focused on the importance of work–life impacts on women’s mental health within the construction industry. Using a SLR approach, this study identified the pressures women in the construction industry face and how these pressures impact a woman’s mental well-being. Review of these studies showed that despite the increasing attention to this field, there is a need for a more inclusive scoped review to identify key focus areas for enhancing DEI across the construction sector.

The thematic nature of previous studies impacted the repetitiveness of literature reviews on the topic; as a result, there is a need for a systematic and comprehensive literature review. Searching for previous literature reviews contributes evidence in support of the scarcity of systematic literature reviews. For example, although a few original research studies have conducted extensive literature reviews on the barriers to women’s increased participation in the field and management of the construction industry, the topic can benefit from a systematically clarified and replicable approach (Naoum et al. 2020; Hasan et al. 2021). Another way that this review paper helps in closing the gap is by employing a search query that yields an inclusive set of results. Although employing terms such as construction in the search query may lead to a higher number of unrelated results, it helps with the inclusivity of the review. Bailey et al. (2022) conducted a review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) approach to highlight the lack of research on disability employment in construction compared with other industries. This paper identifies the gaps regarding the barriers to the employment of disabled people in the construction industry. A limitation of this study is the use of terms such as construction industry instead of construction.

In conclusion, with acknowledging the contributions of the previous studies in this area, comprehensive, recent, and replicable review papers on the topic of DEI are scarce (Hasan et al. 2021) and thus, there is a need for such a study. Therefore, this study attempts to address this gap by conducting a systematic literature review on this topic.

Research Method

The research method is designed to ensure that the reference list comprises a comprehensive data set of relevant literature on the topic of DEI in the construction industry and that they are reproducible. This paper utilized the PRISMA procedure and previous SLRs to design a systematic review process. The PRISMA procedure serves as a comprehensive guideline for conducting systematic reviews (Page et al. 2021). As shown in Fig. 2, the SLR process began by identifying the databases from which to extract relevant literature. To ensure comprehensive coverage of high quality studies in different areas including engineering or social sciences, the search was conducted using Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and Engineering Village databases. The timeframe considered for the literature search was from 2010 until the date of the query’s execution, August 7, 2023. The documents were limited to articles, review articles, and book chapters.

The next step was to develop a comprehensive search string to improve replicability and comparability with our findings over time. Developing a search query that covers the scope of the SLR is critical due to the multidisciplinary nature of the topic. DEI is a multifaceted concept analyzed across various fields, encompassing perspectives from psychology, engineering, education, and more. Creating a well-defined search query helps ensure that the review captures relevant literature from diverse disciplines, avoiding the risk of overlooking valuable insights. This is especially important to prevent inadvertently neglecting prior works that may contribute to a holistic understanding of DEI, such as using a term like construction diversity that might inadvertently exclude pertinent research from other domains. Fig. 3 shows the terms included in the search string and the Boolean operators that characterize the semantic relationships between them.

The search query consisted of three main blocks:

•

Block 1: The first block includes terms related to DEI and different combinations of the terms used in this context. For example, the search will return both “DEI” (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) and “DEIB” (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Belonging), both concepts that are semantically related, but that are not orthographically identical. Similarly, the negative impact of orthographic variability on the comprehensiveness of the search is limited through the use of truncation and wildcard search syntax, e.g., “wom?n$” returns “woman,” “women,” and “women’s.” Similar terms were included to find the papers that have not specifically used the technical DEI terms.

•

Block 2: Connected with an “AND” to the first block, the second block comprises terms concerning the AEC industry. Unlike the queries developed in previous studies, this query has the term Construction independently, which provides a larger and broader number of papers. Therefore, the number of papers significantly increased. The combination of these two blocks led to 25,464 papers only in the WoS database.

•

Block 3: The results are then narrowed down to facilitate the manual inspection of the papers using the “NOT” operator. The creation of the search query was performed as a repetitive process due to the trade-off between the number of initial results yielded and the compromise on the query’s holisticness. The terms excluded using the NOT operator are mainly in the bioscience and chemistry domains. For instance, the combination of diversity and construction resulted in a high number of papers in the biology field. It is important to note that narrowing down the results to the desired scope by manual inspection of the results was not possible due to the high number of papers at each stage. The 42 excluded words in the search query resulted from performing the repetitive task of writing the query, bibliographical analysis of the resulting papers, and then identifying the highly repeated words that are irrelevant to the scope of this study.

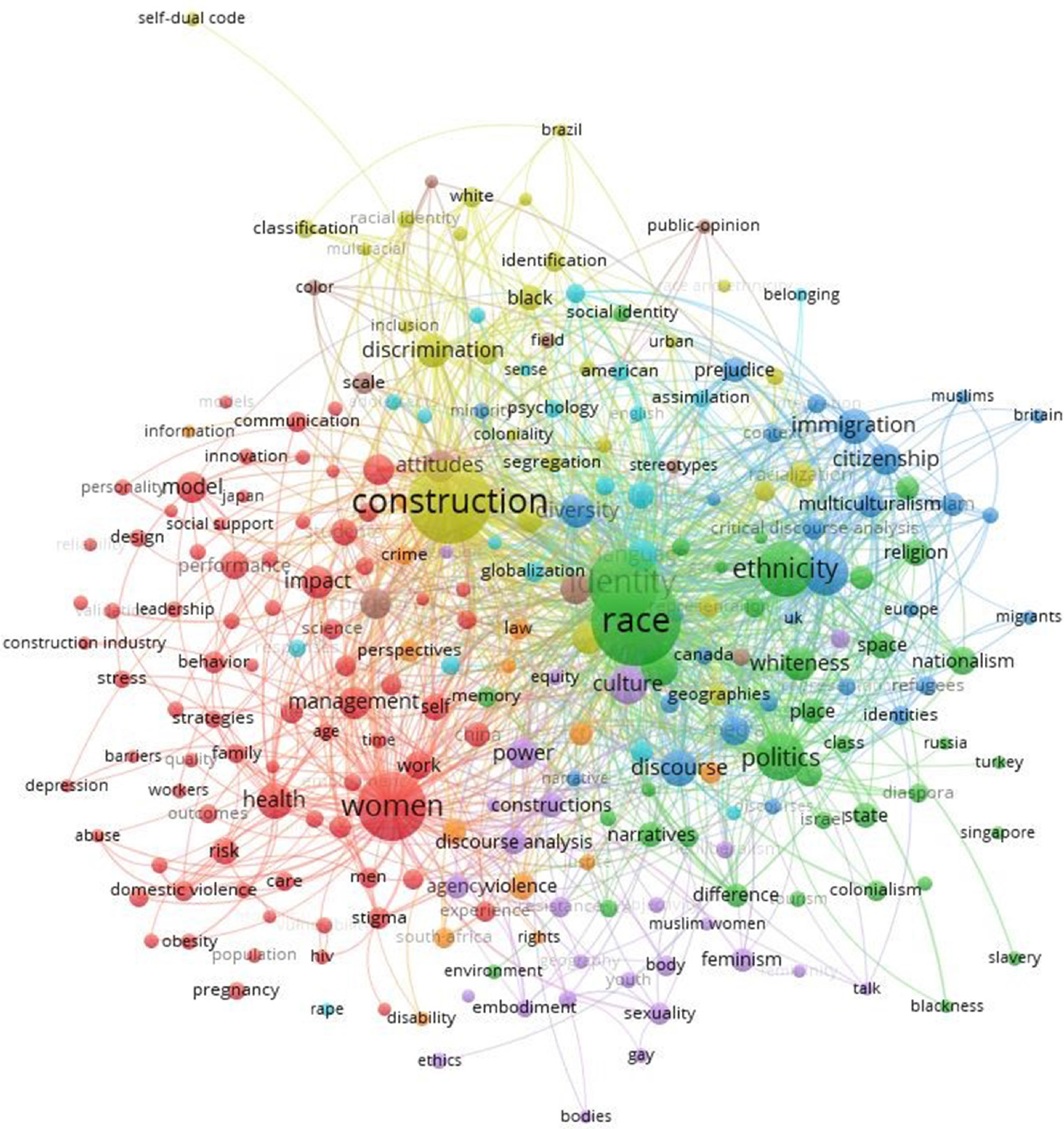

Fig. 4 shows a view of the bibliographical analysis of the final query’s results based on the number of word repetitions. The bibliographical analysis guided modifications to the search query. In each iteration, the broad numbers yielded by the query were visually screened to identify irrelevant words for exclusion. This process continued until the resulting analysis revealed words that aligned with the context and scope of this study. As demonstrated in Fig. 4, an acceptable level of cohesiveness between the results and alignment to the scope of the study can be inferred.

The search was limited to articles, conference papers, and book chapters to ensure the quality and extent of the results. After executing the query separately in each of the previously mentioned databases and eliminating duplicate results, a total of 3,488 papers were available for initial screening. Then, the 3,488 papers were manually screened for removing the undesired papers considering the title, abstract, and keywords. Three questions were used as inclusion or exclusion criteria for decision-making to determine which papers would be included in the SLR’s references data set. First, is the paper relevant to DEI in construction? Second, is the paper closely related to the topic (e.g., DEI in business)? Third, does the paper provide valuable findings for the proposed topic? For example, a paper with the title Let’s Diversify by Changing Culture and Challenging Stereotypes: A Case Study from Professional Construction Higher Education Programmes that included the term diversity in the abstract is within the results, but it is completely unrelated to this study. Eventually, 89 papers were deemed relevant and selected for content analysis.

Several papers were removed in this stage; for instance, the paper with title Promoting Contraceptive Use More Effectively among Unmarried Male Migrants in Construction Sites in China: A Pilot Intervention Trial was excluded because it was focused on public health and medical aspects. After reading the full papers, 84 of those papers were shown to be relevant and within the scope of this SLR.

A full-text qualitative content analysis was performed to acquire an in-depth understanding of the previous literature on the topic (Forman and Damschroder 2007). The content analysis involved identifying key themes discussed in the literature and examining how that information aligned with the objectives of this study, ultimately contributing to the closure of the research gap. Finally, a backward search, which involved manually reviewing the references of relevant papers, was implemented to ensure that all relevant papers were included in the data set developed for this study. In this process, missing papers were identified by examining the reference lists of the selected papers. Here, 11 new papers within the scope of the study were identified and added to the references list from the backward search.

The potential for enriching the search results and reducing the number of papers resulting from the backward search was recognized. In particular, it was identified that the inclusion of terms such as “social procurement,” “gender,” “masculinity,” “diversi*,” “wage,” “employment,” and “career” in the query could enhance the search process by honing in on more relevant and targeted papers. Collectively, 84 papers were found to be relevant after performing the content analysis.

Results

The results section starts by outlining the temporal and locational analysis of the publications. The analysis showcases the attention given to DEI in AEC throughout time in different countries. Categorizing the publications based on their journals further emphasizes on the multidisciplinary nature of the studied subject and the necessity for performing a SLR. Next, diversity groups are identified, and the characteristics that they may affect or be affected by are discussed within the context of the reviewed literature. Lastly, each diversity group is further explored based on the amount of data derived from the literature.

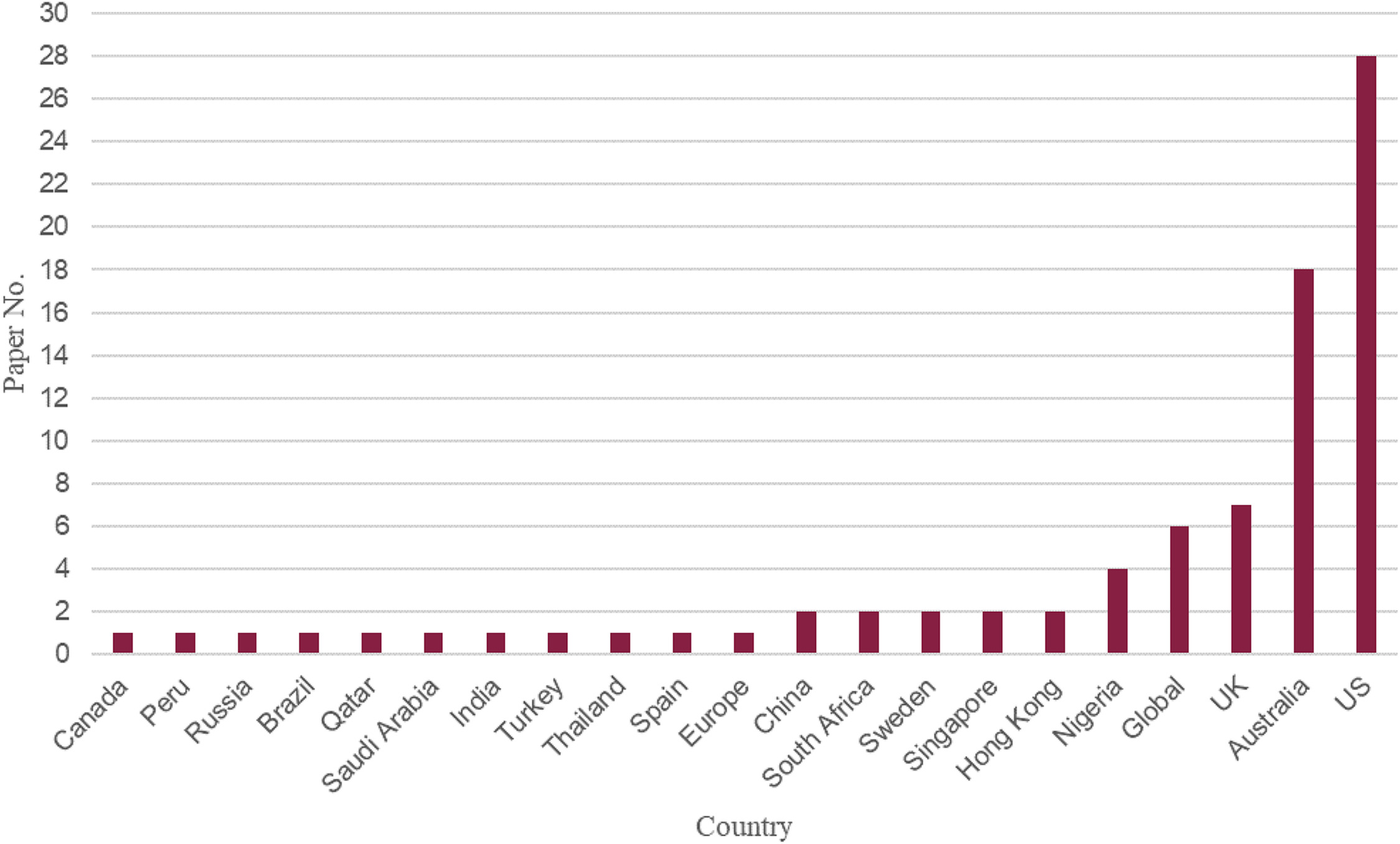

Descriptive analysis is used to summarize the geographic location, publication date, and journals of the literature. Then, the identified barriers, enablers, and specific parameters studied for each DEI group [i.e., women, ethnic minorities, disabled individuals, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ), and incarcerated individuals] are briefly presented based on the extent to which they have been investigated in previous studies. The duplication of studies published in journals or conferences was avoided through manual analysis and synthesis of the findings. Additionally, despite the significant contributions by a few researchers to this topic, research on DEI has not been consistently conducted by specific researchers over time in longitudinal studies. Therefore, the occurrence of specified duplications in this paper was relatively infrequent. Fig. 5 shows an overview of the publications in different countries.

Previous studies have attempted to categorize the literature regionally based on the authors’ country (Powell and Sang 2013). However, it is worth mentioning that in this study the country for each paper is determined from the paper’s content (context of the study) rather than the authors’ affiliation. It is important to accurately identify the target country of each study because different countries have various legislation and societal statuses. This graph demonstrates that more than half of the total papers are studied in the US, Australia, and UK, respectively. Next in line are the papers that have provided a limited scope to a specific region and do not have any implications or findings about a particular country (e.g., review papers), which are categorized as global in the figure.

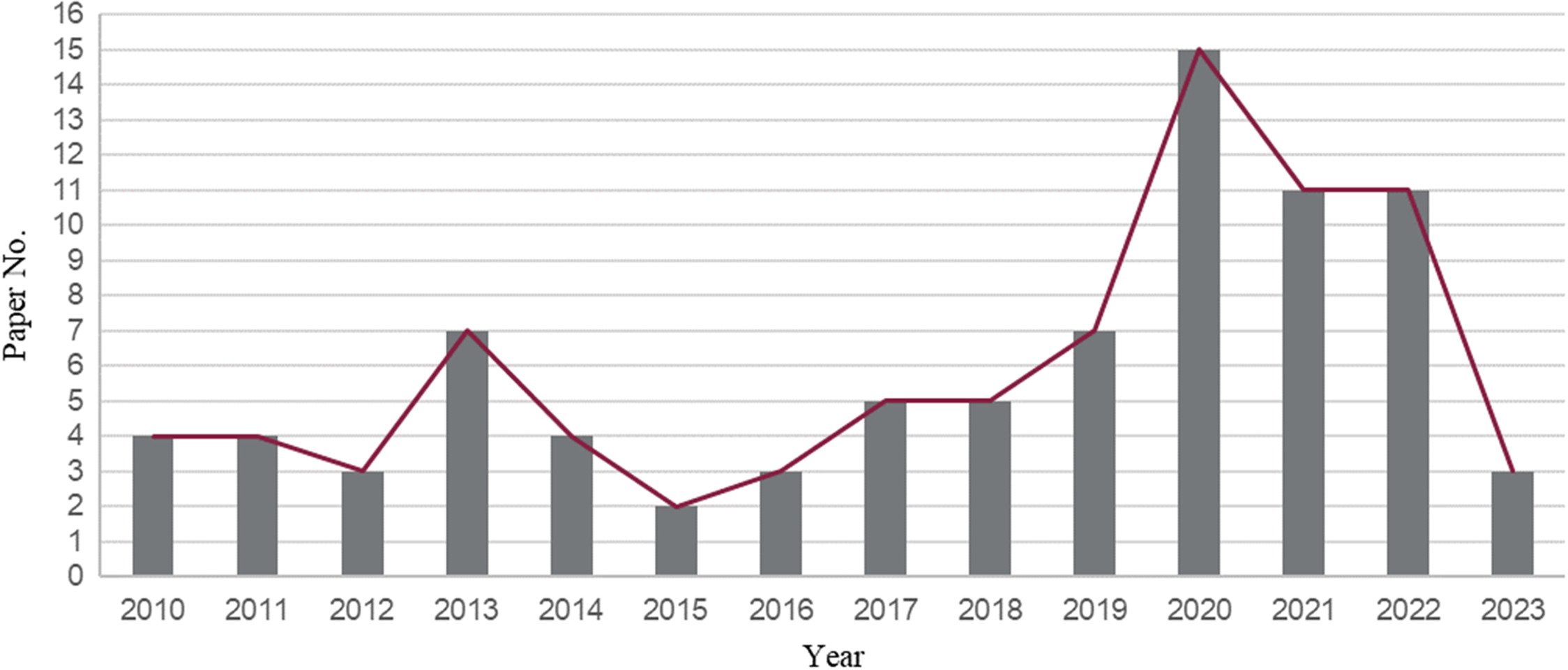

Fig. 6 illustrates the growth rate of publications on DEI in AEC over time. As demonstrated, the number of papers is increasing in a slow but fluctuating trend. The sudden surges in Fig. 6 represent the special issues published in 2013 and 2020, highlighting the significance of top-down academic initiatives on DEI in the AEC industry. Furthermore, the number of papers from 2020 has shown a notable increase, indicating an increasing interest in the topic. Although the recent increase lags behind the dire needs of the industry to address issues such as labor shortages, this review paper hopes to serve as a guide for future research to augment the number of publications in this area.

Table 1 presents the number of papers published in each journal or conference. The Journal of Management in Engineering with 15 papers has the highest impact on this area of research, followed by the Journal of Construction Management and Economics. Twenty-eight papers were published in a variety of journals with only one paper in each, which are grouped and listed as Others. Although some journals have made significant contributions to the topic, the scattered and multidisciplinary nature of the topic of DEI in AEC is evident from the high number of journals with only one relevant published paper. The implemented search method yielded only three results from the Engineering News-Record (ENR) publications. However, it contains a wealth of news, events, and other content that were not listed in the query results.

| Journal | Number of papers |

|---|---|

| Journal of Management in Engineering | 15 |

| Construction Management and Economics | 9 |

| Engineering Construction and Architectural Management | 8 |

| Journal of Construction Engineering and Management | 7 |

| International Journal of Construction Management | 3 |

| Construction Economics and Building | 3 |

| ENR (industry publication) | 3 |

| Data in Brief | 2 |

| Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology | 2 |

| Journal of Construction in Developing Countries | 2 |

| Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice | 2 |

| Others | 28 |

Furthermore, text mining was performed on the abstracts of the reviewed papers to identify and validate clusters of topics and gaps subjectively. The result of the analysis is illustrated in Fig. 7. Although some of the primary clusters in this research domain have been identified, a more inclusive list of clusters is necessary to offer a comprehensive perspective on the subject. Consequently, supplementary clusters were added following a qualitative content analysis.

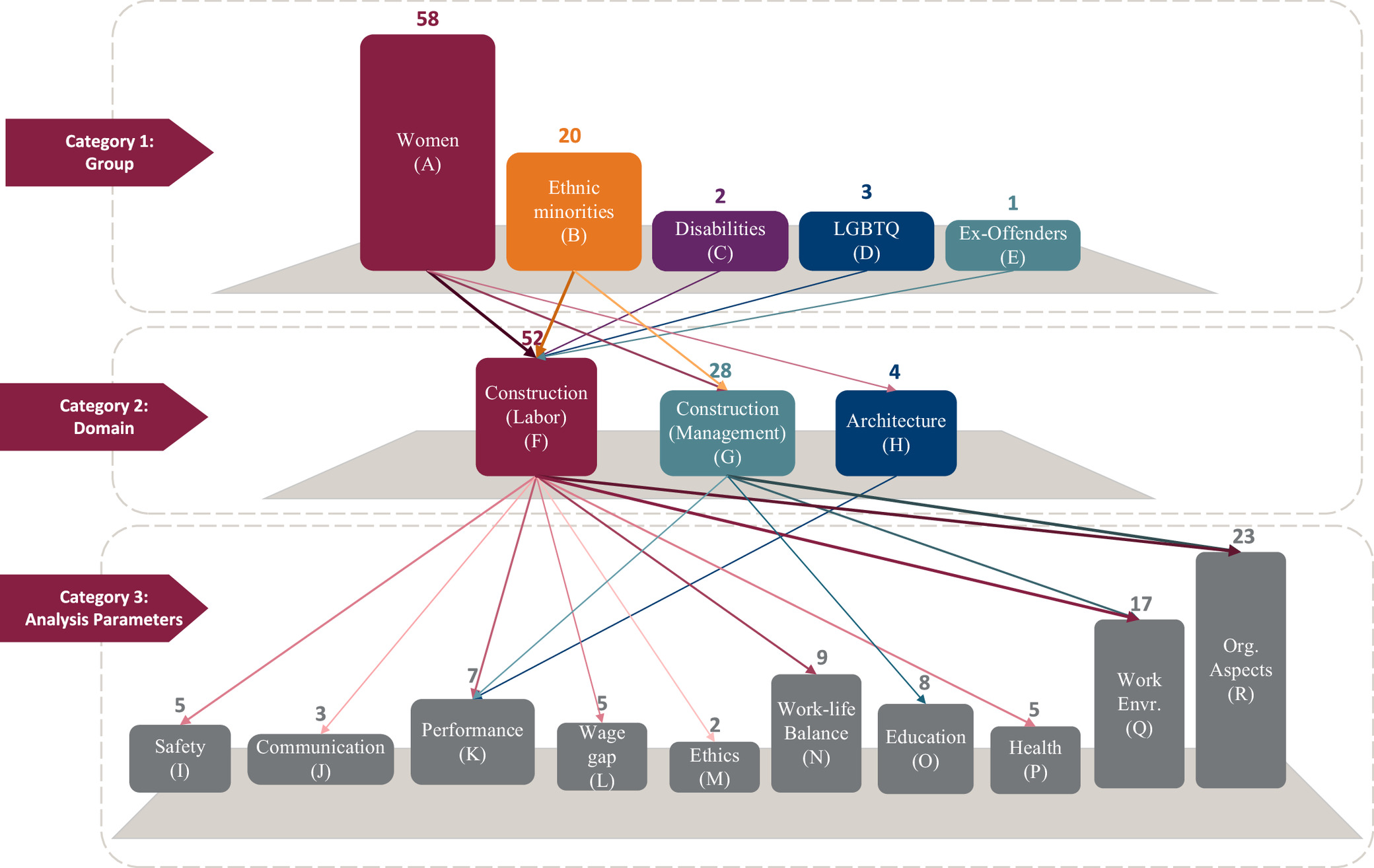

Fig. 8 provides a high-level overview of the current state of the literature. The data were synthesized into three layers: diversity groups, specific AEC domains of study, and the main parameters analyzed. Within the domains layer, construction labor and management were distinguished to address the potential differences in factors faced by these groups. The categorization of parameters was done at a level to be able to discuss them in appropriate detail while avoiding being too general. The categorization of analyzed parameters into 10 specified groups was achieved through careful qualitative consideration of the main focus and contributions of the papers.

The category of Safety includes studies that examine the physical onsite safety of workers. The Communication category refers to papers analyzing language and communication barriers. Within the Performance parameter, papers primarily investigated the performance of underrepresented minorities, either at the individual or firm level. Wage Gap categorizes studies that analyze the salaries of minority groups. The Ethics category consists of studies that approached DEI from an ethical and philosophical perspective. Work–Life Balance encompasses papers that examine the time and energy spent in construction and with family. Education studies investigated the educational status and practices aimed at empowering minorities. Health focuses on the mental health and overall well-being of the workforce. The Work Environment category includes papers that concentrate on work culture, examining physical, social, and psychological aspects that influence DEI. Papers grouped under Organizational Aspects explore managerial actions and assessments linked to the DEI performance of organizations or firms.

The height of the columns presented in each layer represents the approximate measure of concentration in each group, further elaborated by the number of papers above each column. The layers are connected with links that represent the relationship between the mentioned layers. The links display the routes that previous literature has taken in studying DEI in the AEC sector, with the shade of the links varying based on the number of studies analyzing that relationship.

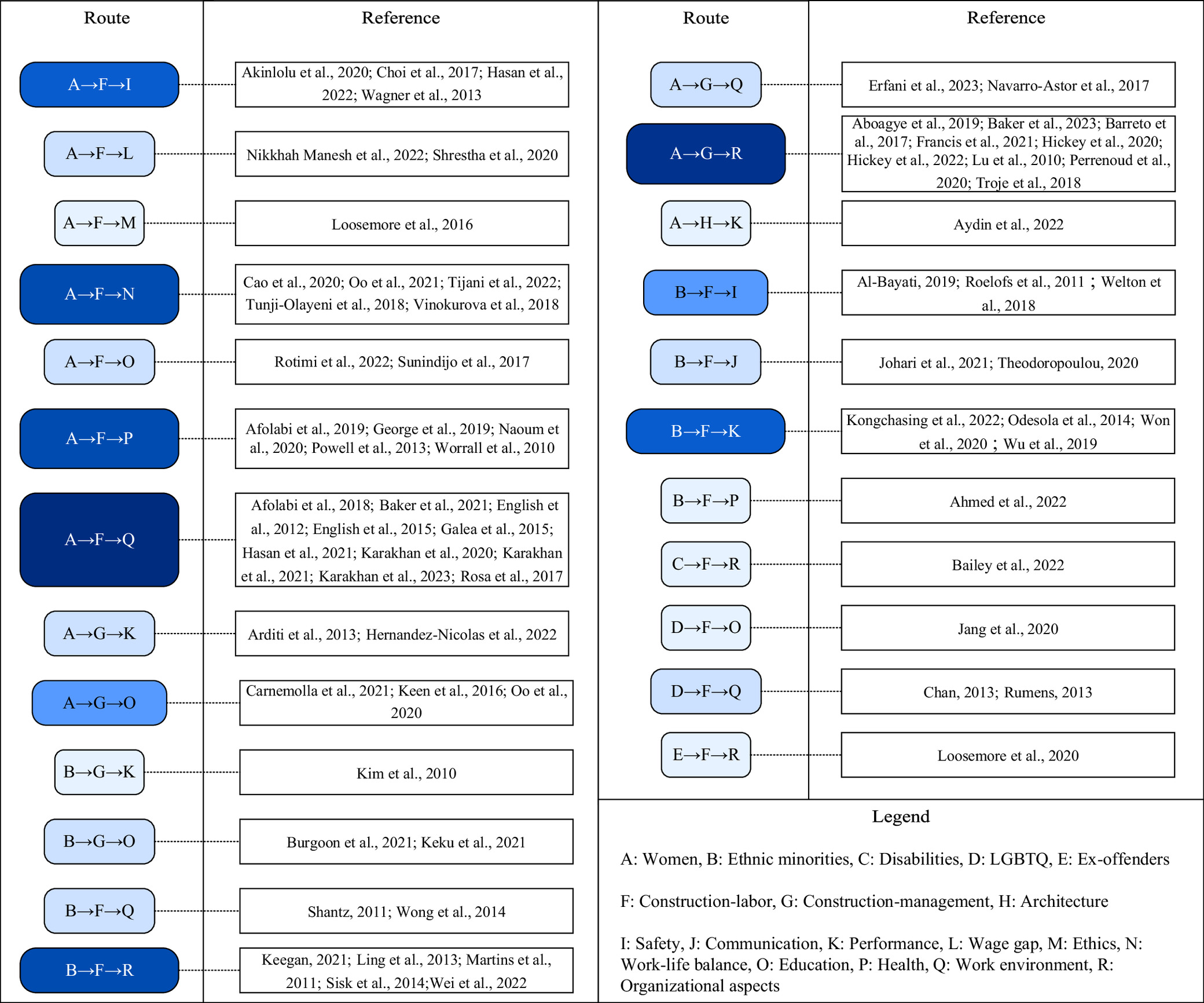

The strongest links observed were in the study of women in construction skilled trades, particularly investigating organizational aspects and the role of the work environment. However, many of the links between the specified groups are weak, highlighting the need for further investigations in future studies. Additionally, numerous potential links between the groups within each category are absent, indicating a lack of research and a gap in those areas. Each element in Fig. 8 is labeled to facilitate the visualization of the investigated topics in Fig. 9.

Figs. 8 and 9 were drawn considering the main topics/contribution of the reviewed papers. The topic of DEI is multidisciplinary, and each paper can potentially contribute to multiple parameters and groups. However, side topics/contributions were not included in the counting because, although the main focus of each paper is evident, the inclusion and the extent of counting their side topics could become arbitrary and subject to bias.

Figs. 8 and 9 are complementary, offering different information and perspectives. Fig. 8 provides a high-level overview of the efforts made to advance knowledge in the categorized areas, whereas Fig. 9 offers a more detailed technical view that depicts every path taken, considering the main contributions of the reviewed studies. Fig. 9 provides the references for researchers that are interested in a specific topic in a straightforward way. The size of the boxes is proportional to the amount of research performed on each topic. Future research should not be limited to only the previously identified variables; there are many potential routes that have not been explored and remain as research gaps. For example, only one study has investigated the performance of ethnic minorities in managerial positions in the construction industry (Kim and Arditi 2010). Another example is the absence of studies evaluating the performance or contributions of female construction workers.

Reviewing the previous studies showed a higher share of studies on the issues that hinder women’s participation in the AEC sector, but not much attention has been given to the barriers for ethnicity or disabled workers as an example. The categorization of the results is done based on the amount of content on each topic in the literature. The results are presented by first discussing the barriers that women face and the solutions provided. Health and safety is another topic explored with regard to women in the AEC industry. The ethnic minorities in construction are then discussed with an emphasis on safety and communication issues, and the managerial initiatives to address their DEI-related issues. Next, the studies evaluating other groups including LGBTQ, disabled, and incarcerated individuals are discussed.

Enablers and Barriers to Women Entering Construction

Barriers

Many studies have focused on the barriers, challenges, and issues that women face in the AEC industry. Improving the presence of women in the construction industry is crucial due to increasing demand and ethical considerations. Therefore, investigating the barriers to their recruitment and retention is essential (Loosemore and Lim 2016). Working conditions, discrimination, inflexible work conditions, long working hours, work–family balance, foul language, poor public opinion of construction, alienation, and sexual harassment are among the reasons women face hardships in construction (Arditi et al. 2013).

Working environment has been a significant problem hindering women’s higher involvement in the AEC sector. Some male workers believe that bringing in more female workers brings more competition and adversely changes the current culture. Even when no direct discrimination is observed or identified, women believe that they have to work harder to earn respect (English and Hay 2015). Female leaders in construction are seen as competent as their male counterparts; however, they are less likable (men’s likability score was found to be 51%, and women’s was 28%). Male leaders receive praise for their leadership, technical, management, and trustworthiness, whereas female leaders receive more praise for their creativity, maturity, communication, and problem-solving abilities. According to colleagues’ LinkedIn recommendations, male leaders score almost twice as likable as women leaders (Erfani et al. 2023).

Previous literature has identified work-life balance as another major problem experienced by female employees within the AEC sector (Tijani et al. 2022). For example, women with children have identified attending their children’s school events, helping them with homework, and taking them to school as significant barriers resulting from work–life imbalance (Tunji-Olayeni et al. 2018). Another term used interchangeably in the literature is work–family conflict. Findings have indicated that although job performance is not highly affected by work–family conflict, job satisfaction is negatively impacted (Cao et al. 2020).

Low retention rates of female employees in AEC are another underlying reason for their low numbers. For example, women leave the industry at a rate roughly 40% higher than men in Australia’s construction industry (Sunindijo and Kamardeen 2017). It is important to acknowledge that the issues women in AEC encounter change as they progress. The challenges that women face are not limited to their recruitment, but also vary as they progress and gain experience in the industry (Aydin and Erbil 2022). Several studies have attempted to analyze and document the career journeys of women in construction firms (Lu and Sexton 2010). Although there have been some success stories of women in these roles, the barriers they face lead to their lower retention rates. Eventually, they experience zigzag career paths and are outpaced by their male counterparts (Hickey et al. 2022).

The issues that women face in field and managerial positions within construction companies have been shown to differ despite inherent similarities. The similarities stem from the masculine notion embedded in the construction industry, which presents an underlying threat to gender diversity. For example, tradeswomen in construction threaten the inherent masculinity and the presumed gender order, which involves women’s subordination. Tradesmen neutralize these threats by labeling and objectifying women. Additionally, sexual and humorous expressions might also contribute to the creation of a toxic masculine identity in this field (George and Loosemore 2019).

Barreto et al. (2017) investigated men and women’s perceptions regarding the barriers women in AEC encounter. The findings showed that men and women have different understandings. Men interpret womanhood as a form of positive discrimination, which can have an aggravating impact on the work environment. Harassment has been an ongoing issue for women in the construction industry (Regis et al. 2019). Benevolent sexism is another challenge that women in the construction industry face (Worrall et al. 2010).

Many studies have focused on exploring the barriers faced by female workers in the construction industry (Sunindijo and Kamardeen 2017), and others have attempted to analyze the challenges faced by women in managerial positions within construction firms (Perrenoud et al. 2020). The challenges that women face change as they progress and attain senior roles within the firms. Women not only face glass ceilings when trying to get internally promoted, but there is also another theory named the leaky pipeline theory, which states that re-entry to their jobs is difficult for women after they depart for various reasons (Aboagye-Nimo et al. 2019; Hasan et al. 2021).

Arditi et al. (2013) investigated the competencies of construction managers by analyzing and comparing men and women separately to find out why there are fewer women in managerial roles in construction companies. The results showed that male managers rated themselves better than women in two competencies, resilience and decision-making, whereas women found themselves better at sensitivity. However, they are similar in many parameters, indicating that there are no significant competency differences between male and female managers on average. Nevertheless, it is crucial to avoid employment based solely on merit and strive to increase diversity in recruitment without altruism (Martins et al. 2011). Hernandez-Nicolas et al. (2022) examined the performance of construction firms with female chief executive officers (CEOs). Firms with female CEOs have lower debt levels but have also shown to be less profitable. However, this could be due to the perception that minorities are tokenized and therefore marginalized.

The wage gap is another barrier to achieving gender equality in the construction industry. Manesh et al. (2020) presented a geographical analysis of the gender-based wage gap in the US. Although the spatial distribution of the wage gap in construction is random, the gap between men’s and women’s wages was confirmed. Furthermore, an analysis of US statistics showed that the wage gap trend has remained steady over the years.

Enablers

Each of the DEI groups introduced needs to be studied separately due to their inherent differences. Although studies in this regard are limited, most of them have focused on proposing enablers to improve the representation of women in the AEC sector. Historically, women have faced many challenges in the AEC industry, and individual efforts by female architects to remove these barriers are not a solution (Aydin and Erbil 2022). The proposed solutions by organizations are costly and not always productive. Gender diversity in AEC can bring external benefits such as improved skill shortage, enhanced business insights, a more motivated staff, and improved customer satisfaction, as well as internal benefits such as better company performance, integration of diverse views, lower turnover, and improved creativity from a business case standpoint. However, more focus has been placed on the external benefits in AEC (Francis and Michielsens 2021).

Due to the various aspects of the low levels of diversity, equity, and inclusion in the construction industry, proposed best practices should consider different aspects (Karakhan et al. 2023). Enablers for women range from deep psychological actions to slight modifications in job sites. For instance, by strengthening women’s perception of their own identity and personality, common stereotypes of women being unable and not tough enough for construction may fade. Having mentors and role models can also be helpful, and bathrooms in construction sites can make a difference (Afolabi et al. 2019).

The findings indicate a direct correlation between the number of women in managerial positions and the recruitment and promotion of more women in such positions (Baker et al. 2023). The perceived best practices include flexibility in work, transparent criteria for promotion, training for returning to work (e.g., after maternity leave), and outreach programs for students. However, a one-size-fits-all approach may not be effective (Naoum et al. 2020). Lastly, dedication, determination, and independence were the top three success factors for women in the construction industry (Rosa et al. 2017).

To propose best practices, one must consider the critical role of education. Previous studies have identified the lack of retention of women who enter the construction industry through education (Aboagye-Nimo et al. 2019). Keen and Salvatorelli (2016) studied the difference between students’ perceptions and the reality of the construction industry. The results identified three points of consistency between the expectations from education and the actual state of the industry, including salaries, work hours, and workforce gender composition. However, inconsistencies included employment benefits, academic degree attainment, and professional engineering licensure. Oo et al. (2020) investigated the views of recently graduated women who have joined the construction industry. The main motivations for women joining construction included career opportunities, belief in higher salaries, and strong confidence in performing job tasks. In contrast to the prevailing belief, their study highlights a different perspective by finding that job satisfaction and the level of expectations met were high among early career women.

To propose best practices, enablers, or good solutions, further investigation is needed after implementation. Careful assessment of special programs such as Helping Hands is necessary as continued assistance can have adverse effects (Karakhan et al. 2021). For example, Australian construction firms are required to develop formal action plans to improve gender equality and diversity. However, the findings indicated that gender equality and diversity initiatives often fail to perform as expected. Companies’ leaders develop the plans based on legal requirements, personal views of justice, and individual biases (Baker et al. 2021).

Health and Safety

The work stress that affects the mental health of workers is an underlying reason for the low participation and retention of women in the construction industry. Studies have shown that women suffer from anxiety more than men, but there is no difference in the resulting level of depression between the two genders. The top stressors are the same for both genders and include time pressure, excessive workload, long work hours, and unpleasant work environments. Women, however, experience more discrimination and harassment (Sunindijo and Kamardeen 2017). Several studies have focused on the importance of work–life balance on women’s mental health within the construction industry. Previous literature in this regard can be categorized into three groups: challenges, workplace consequences, and well-being outcomes. Onsite jobs have the highest number of issues compared with other construction careers (Rotimi et al. 2022). The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on women in the construction workforce have also been analyzed in previous studies. The results showed that women’s domestic responsibilities increased, and work–life balance was placed under more pressure in those conditions (Oo et al. 2021).

Safety risks are also a potential deterrent to attracting women to the construction industry (Akinlolu et al. 2020). Analyzing historical accident data from 2008 to 2019 showed that the annual average number of accidents experienced by women in the construction industry was 307, but it did not follow a specific trend and fluctuated. Both female professionals and manual workers had a lower incident rate than their male counterparts in Australia (Hasan and Kamardeen 2022). English and Bowen (2012) explored the health and safety of workers and women’s perception of it on construction sites. The concept of “critical mass” was defined to indicate that a certain number of women in construction are needed to achieve a sufficient level of comfort and safety within the site. Male chauvinism, sexist attitudes, poor safety, and attitudes toward gender are among the barriers women face upon entry into South Africa’s construction industry. Although more comprehensive research is needed, Wagner et al. (2013) suggested that appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and work clothing can help retain female skilled trades. Improvements in work clothing can increase the job satisfaction of women in construction. Although PPE for women has been designed and is being sold, the accessibility and distribution low (Choi et al. 2017; Wagner et al. 2013).

Ethnic and Racial Minorities’ Challenges and Management

More attention and support are needed to improve equity among ethnic and racial minorities in the construction industry (Keegan 2021). Although there have been instances where workers who have been subjected to discriminatory behaviors have filed and won substantial lawsuits against firms, the overall conditions remain unfavorable (Shantz 2011). The occurrence of certain conditions, such as natural disasters when there is a sudden need for a large workforce, provides an opportunity to enhance workforce diversity by employing local minorities.

However, studies have shown that the disadvantages experienced by minority workers intensify (Sisk and Bankston 2014). Kongchasing and Sua-iam (2022) categorized the issues that immigrant workers experience into five main groups: skills and performance, safety, social and public health, legal and regulatory, and communication. Legal issues are crucial in reducing labor turnover because migrant employees often have limited job security and contracts.

The involvement of Hispanic workers in the construction industry’s workforce has led to a high rate of injury and accidents for them. Communication barriers are only one marginal cause of this issue. The identified factors include feeling higher productivity pressures, being subjected to disrespectful attitudes, and being more likely to tolerate unsafe conditions (Roelofs et al. 2011). Hispanic workers with certain conditions (such as being temporary, working in small companies, or drinking) have a poorer perception of the safety climate. The underlying reasons include supervisor’s pressure, competition for jobs, and discouragement from addressing safety concerns (Welton et al. 2018). Active cultural differences have been identified as an underlying cause, and therefore, better management approaches are needed. For instance, Al-Bayati (2019) attempted to provide a training module to improve the overall safety of diverse construction crews.

Communication in multilingual and ethnically diverse environments is another subject that has been investigated to a limited extent and needs further attention (Theodoropoulou 2020). Studies have shown that improved listening and writing skills of workers enhance construction labor productivity, whereas improved reading and speaking skills can have negative effects (Johari and Jha 2021). However, in some countries, communication has not been identified as a persistent problem.

The suggested managerial actions in a diverse workforce have been identified as employing highly skilled workers, administering employment contracts, providing strict supervision, rewarding workers who take initiative, and providing safety training for workers (Ling et al. 2013). Ethnic minority workers demand nonmonetary incentives and tend to group themselves with those of similar cultural or ethnic backgrounds. This may lead to divisions that negatively impact communication, safety, and productivity on construction sites (Troje and Kadefors 2018). In addition, immigrant workers face a number of issues including poor connections with locals, subpar living conditions, and challenges with professional identity (Vinokurova et al. 2018). Mental health and stress levels are as important as safety issues for ethnic minorities in construction (Ahmed et al. 2022).

Fostering integration and a sense of belonging among diverse workforces extends beyond mere representation. Wei and Chan (2022) analyzed wage arrears (delayed payments) and protests and collective actions by workers. The results indicated that the recruitment method of immigrant workers leads to different network structures, which play an important role in creating a foundation for collective actions (Wei and Chan 2022). Understanding the psychological attributes involved in managing immigrant workers underscores the significance of instilling a sense of belonging within the workforce. This can be achieved by providing labor rights, respect, proper working conditions, and dignity to the workers (Petrini and Wettergren 2022).

Other Groups and the Need for More Attention

Although different methods and frameworks have been used to study DEI, there is an underlying common cause for the low participation of all groups: unjust treatment of one group by another (Loosemore and Lim 2016). Very few best practices have been proposed for improving overall DEI within projects. The UK Olympic Delivery Authority adopted an approach with its contractors called “business assurance.” First, contractors completed a self-assessment of their organizational capability to deliver DEI. Then, action plans were created and balanced with realistic goals by the contractors. A program was created to provide opportunities for people to experience working on the sites and then get hired (Martins et al. 2011).

Moreover, it is essential to acknowledge the possibility of undercounting ethnic minorities in estimates of their representation due to legal residency issues they may face (Wagner et al. 2013). Similarly, underreporting is a challenge in assessing the representation of LGBTQ individuals. One significant contributing factor is the lack of disclosure by members of these groups (Chan 2013). The same issue has been identified for disabled individuals working in construction due to fear of being perceived as incapable and losing job opportunities (Bailey et al. 2022). Therefore, creating a supportive and encouraging environment for people to identify their demographic and disabilities without the fear of retaliation or impact on their career can have a positive impact.

Kim and Arditi (2010) investigated the performance of minority firms (those owned by ethnic minorities, disabled people, and women) compared with nonminorities. The results showed that, overall, nonminority firms outperformed minority firms. However, upon further analysis, it was found that there were no differences between large and old minority and nonminority firms. Small and young nonminority firms, however, outperformed minority firms. Nonminorities outperformed minority firms in terms of financial performance and information technology (IT) capabilities.

Despite the recent increase in studies investigating DEI in the construction industry, disabilities remain largely unaddressed. This is significant because people with disabilities are at a higher risk of injuries in the construction industry. Bailey et al. (2022) categorized the literature on disability and employment into themes. The first theme was laws and policies to prevent discrimination against disabled people. Another theme was stigma or attitude barriers. Strategies such as education and sharing stories of success can be potential solutions. Other themes included disclosure, accommodations, disability organizations, and providing support to employers (Bailey et al. 2022).

The masculinity of the construction industry has been identified as an obstacle to diversification in the sector. Chan (2013) attempted to analyze alternatives to masculinity in construction by expanding on queer theory based on the life stories of nine nonheterosexual individuals. The conventional masculinity culture of the construction industry is a problem for LGBTQ individuals, which hinders their participation and disclosure (Chan 2013). Rumens (2013) used queer theory to disrupt the notion of gender and sexuality as fixed and universal. That study argued that the current approaches to studying the male-dominated culture of the construction workforce are ineffective (Rumens 2013).

Loosemore et al. (2020) focused on a completely neglected group of the construction workforce, namely incarcerated individuals (also referred to as ex-offenders or second chances), by investigating employers’ views on the matter. The results showed that 30.9% of subcontractors had previously hired ex-offenders, 30.9% had not hired ex-offenders but were willing to do so, and 38.3% had not hired ex-offenders and were not willing to hire them.

Discussion

In this section, a synthesis of findings is performed by clustering related information from previous studies, such as the underlying differences between similar barriers experienced by women or ethnic minorities, as well as the utilized methodologies. Then, the research gaps in studying diversity groups (i.e., women, ethnic minorities, and other groups) are presented. Next, future research trends are mentioned from a high-level integrated view. Lastly, the provided solutions and suggestions for dealing with low DEI levels in the construction industry are discussed. Although many studies have explored the challenges and opportunities for women in construction, investigations into DEI groups (e.g., ethnic minorities) and barriers to their increased participation have remained limited and even uncovered for some underrepresented groups (e.g., senior workers).

Recognizing the Similarities and Differences in Diversity Management

The ethical and strategic motivations for increasing diversity in the construction workforce are similar for different DEI groups, but the barriers they face differ. For example, women may face safety issues due to the lack of personal protective equipment, whereas immigrants and ethnic minorities may experience safety issues due to communication problems and lack of training. Barriers can be grouped into categories such as work culture and environment, work–family balance, health and safety, organizational issues, wage gaps, and communication inefficiencies. Although some studies have suggested solutions for improving certain aspects of DEI in the AEC sector, such as safety programs for ethnic minority workers, there is a limited number of studies evaluating the effectiveness of these best practices.

Utilized Methods

Most of the previous studies have used qualitative data collection methods such as surveys, focus groups, and interviews to explore relevant parameters and gather subjects’ perceptions. However, generalizing the results obtained from qualitative data can be problematic in terms of reliability and validity. For example, very few studies have included the views of men in analyzing the underrepresentation of women in construction (Naoum et al. 2020). Additionally, the data were usually collected from limited groups within a company, project, or university using methods such as snowball sampling, which may introduce biases that need to be considered and avoided.

The workforce should not be polarized by gender or ethnicity because it can negatively impact mental health, work culture, and productivity. Any proposed solutions or best practices should take this into account to prevent issues like nepotism. Examining the concept of masculinity in the construction industry work environment can offer a new perspective and prevent gender polarization (Rumens 2013). There is no consistent method for evaluating the performance of underrepresented groups, making it difficult to determine their performance. Therefore, identifying relevant parameters and proposing effective performance measurements at various levels of the construction industry can be useful.

Previous studies have explored the capabilities of underrepresented DEI groups in the AEC workforce and managerial positions to a certain extent. However, there is a need for further investigation into the potential benefits that diversification could bring. Although previous studies have identified some of the challenges faced by underrepresented groups in the industry, there are still gaps that need to be addressed in future research.

Knowledge Gaps and Future Research

Despite the increasing efforts to investigate the topic of a diverse and sustainable workforce, there is still much progress to be made. Studies are needed to investigate the applicability of ethical theories and business case perspectives to increase DEI in the AEC sector. The gaps are categorized based on the results section. Firstly, research gaps regarding the study of women in AEC are specified. Secondly, the gaps in studying immigrants and ethnic and racial minorities are illustrated. Thirdly, the lack of research on other diversity groups, such as disabled individuals, is stated. Lastly, the dearth of research evaluating the interactions that the involvement of different groups might have is discussed.

Need for a Deeper Investigation of Barriers for Women

From a higher-level perspective, it is necessary to examine the interactions and relationships between various barriers and parameters. Although the barriers to women’s recruitment and retention in the AEC sector have been identified at various levels and regions, it has not been explored how these barriers influence or exacerbate each other. Therefore, more attention needs to be paid to theorizing and inferring the connections between the causes and effects of the challenges identified and the consequences that women face. For instance, there is a gap in understanding the potential effects of a poor work environment on performance. Additionally, most previous studies have limitations in terms of generalizing the results. However, it is worth mentioning that reviewing the results of different papers from various regions, years, and individual backgrounds can confirm the validity of the previous studies.

From a more detailed perspective, there is a gap in performing studies that attempt to analyze the roots of each issue. For example, an in-depth analysis of the wage gap can provide insights into the amount and underlying reasons for the inequity. The applicability of theories such as the glass ceiling and leaky pipeline in explaining the low retention of women in construction has been extensively reviewed. However, introducing new theories and assessing their applicability to the AEC sector regarding societal changes in the last decades can be beneficial. For example, stewardship theory and the influence of role models in attracting and retaining women in the workforce, as well as construction educational programs, can provide valuable insights.

Addressing Ethnic and Racial Minorities’ Challenges

More attention needs to be given to the communication and linguistic issues faced by ethnic minorities in the construction industry. The effectiveness of language training programs or technological solutions to address communication issues has been limitedly investigated. Furthermore, there is a lack of quantitative data on injuries among Hispanic and other underrepresented workers. The safety of Hispanic workers has been studied only to a limited extent, and there is a need for more statistical analysis. Specific attention should be given to the needs of different countries, cultures, and their respective minorities. For instance, Hispanics are the largest ethnic minority in the US construction industry and face unique challenges. Additionally, it would be valuable to analyze the networks that ethnic groups form in the workforce. Finally, there is a need for empirical research on how increasing diversity in construction can impact communication and performance, which has mostly been studied in terms of safety rather than productivity.

Advancing Diversity by Including Other Groups

There are diversity groups that have gone completely unnoticed, such as elder workers in construction. Other groups, such as LGBTQ individuals and disabled individuals, have been very scarcely reviewed. Research specific to the construction industry regarding how organizational culture, structure, or other factors affect the employment of disabled people has been limited. In addition, reporting on the effectiveness of proposed strategies for the workforce is also neglected. Lastly, finding methods that motivate these groups to disclose their information can also be helpful.

Finally, studying the potential cause and effect relationships between barriers and parameters that affect each group can yield valuable insights. Taking a broader perspective, it is important to investigate how the presence of each group can impact others. Analyzing statistical data to assess the current status, performance aspects, and the effectiveness of initiatives in increasing participation levels can also be beneficial.

New Solutions for Old Problems

Construction industry has been struggling with low DEI levels for a considerable period, and previous solutions have proven ineffective. Table 2 provides a brief overview of the targeted groups and initiatives proposed by previous literature as best practices. As indicated in Table 2, the number of papers that have proposed, implemented, and evaluated the effectiveness of best practices is scarce. Most papers have only mentioned the best practices as potential solutions after conducting a study on another subject, such as barrier identification. Moreover, none of the studies have proposed a best practice and evaluated its efficiency.

| Suggestion | References | Group | Evaluated? | Main topic of the paper? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funding female mentor or role model programs, sharing success stories | Afolabi et al. (2019) | Women | No | No |

| Collective action by women | Aydin and Erbil (2022) | Women | No | No |

| Increasing the number of women in managerial positions to support the progress of more women | Baker et al. (2023) | Women | No | Yes |

| Unified communication language | Bryce et al. (2019) | Ethnicities | No | No |

| Assessing the industry initiatives | Francis and Michielsens (2021) | Women | No | No |

| Proposing general tips in developing future best practices by evaluating the diversification policies | Galea et al. (2015) | Women | No | Yes |

| Assessment parameters for measuring the DEI level in the construction workforce of the companies (e.g., assessing the wage gaps) | Karakhan et al. (2021) | Women/ethnicities | No | Yes |

| Flexibility in work (work–life balance), transparent promotion criteria, return to work training (e.g., maternity leave), outreach programs for students | Naoum et al. (2020) | Women | No | No |

| Identifying motivations, expectations, and satisfaction | Oo et al. (2020) | Women | No | No |

| Increased flexibility, support, re-employment of former employees, developing a supportive organizational culture | Regis et al. (2019) | Women | No | Yes |

Although previous studies have attempted to analyze the competencies of women in managerial positions in the construction sector, it remains unclear whether a career in construction is a good fit for female workers and how their presence may affect project performance. The same argument applies to other DEI groups. Increasing the number of women and groups such as ex-offenders may seem mutually exclusive. With these considerations in mind, this section provides a brief review of the best practices, good practices, enablers, or effective solutions that have been interchangeably used in the literature. Superficial and unfounded development of programs and legislation can lead to unintended consequences and may even prove to be counterproductive.

Targeting each population group and providing suggested measures can be a direction for future researchers and practitioners advocating for DEI in construction. The developed best practices should consider the complexities associated with each group. For example, age, education, experience, and other relevant factors should be taken into consideration when suggesting solutions for increasing the participation of women.

Conclusion

The low levels of DEI in the AEC workforce have become a growing concern from both business and ethical perspectives. The underrepresentation of certain groups in the AEC sector can result in a lack of diverse perspectives and innovations, which can negatively impact the industry’s overall success. Despite efforts made by legislators, organizations, and other stakeholders, progress has been minimal. This is because the lack of DEI is a complex problem with multiple aspects. It is essential for the AEC sector to take proactive steps to address this issue and create a more equitable industry.

To address the challenges, this study conducted a SLR to identify the barriers, research gaps, and best practices that are embedded in the literature to improve DEI in the AEC sector. This study makes several contributions to the existing literature on DEI in the AEC sector. Firstly, it provides a comprehensive overview of the challenges or enablers that each diversity group faces in different domains of the AEC sector. Secondly, the comprehensive review enables this paper to find the gaps and limitations of previous studies. Thirdly, it provides recommendations for future research based on the identified gaps.

The findings of the SLR provide insights into the current state of research in this area, highlighting gaps, opportunities, and promising practices that can inform future efforts to promote DEI in the AEC sector. Despite the extensive scope of this study, it is evident that the literature on the topic of DEI in AEC is lacking. Based on the review, the diversity groups studied were women, ethnic minorities, disabled individuals, LGBTQ individuals, and ex-offenders, listed in order of the number of studies in which they were included. However, a more in-depth analysis of the identified barriers and their relations is needed. Further understanding of the barriers can help provide more effective best practices and evaluate them. Another gap explored in this review paper is the lack of research on how technological advancements in the construction industry specifically affect DEI.

Despite the benefits of the performed SLR, the developed query and scope can be customized in future studies. The search query could be modified to include other relevant terms, such as social procurement, to broaden the search scope. Future SLRs can utilize the findings of this study to narrow down the research to a specific area of interest. For example, future studies can utilize terms such as best/good practice, enabler, or solution to identify efforts made to improve DEI in other industries and tailor them to the AEC sector.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aboagye-Nimo, E., H. Wood, and J. Collison. 2019. “Complexity of women’s modern-day challenges in construction.” Eng. Constr. Archit. Manage. 26 (11): 2550–2565. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-09-2018-0421.

Afolabi, A., R. Ojelabi, P. F. Tunji-Olayeni, and T. O. Mosaku. 2018. “Survey datasets on women participation in green jobs in the construction industry.” Data Brief 17 (Mar): 856–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2018.02.009.

Afolabi, A., O. Oyeyipo, R. Ojelabi, and T. Patience. 2019. “Balancing the female identity in the construction industry.” J. Constr. Dev. Countries 24 (2): 83–104. https://doi.org/10.21315/jcdc2019.24.2.4.

Ahmed, K., M. Leung, and L. Ojo. 2022. “An exploratory study to identify key stressors of ethnic minority workers in the construction industry.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 148 (5): 04022014. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002261.

Akinlolu, M., O. Olalusi, and T. Haupt. 2020. “A scientometric review and meta-analysis of the health and safety of women in construction: Structure and research trends.” J. Eng. Des. Technol. 19 (2): 446–466. https://doi.org/10.1108/jedt-07-2020-0291.

Al-Bayati, A. 2019. “Satisfying the need for diversity training for Hispanic construction workers and their supervisors at US construction workplaces: A case Study.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 145 (6): 05019007. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001663.

Arditi, D., P. Gluch, and M. Holmdahl. 2013. “Managerial competencies of female and male managers in the Swedish construction industry.” Construct. Manage. Econ. 31 (9): 979–990. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2013.828845.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2022. “Characteristics spotlight: Selected insights of payroll jobs distributions.” Accessed October 25, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/characteristics-spotlight-2022#sex-by-industry.

Aydin, M., and Y. Erbil. 2022. “Career barriers of women architects in the construction sector.” ICONARP Int. J. Archit. Plann. 9 (1): 50–61. https://doi.org/10.15320/iconarp.2022.197.

Bailey, S., P. Carnemolla, M. Loosemore, S. Darcy, and S. Sankaran. 2022. “A critical scoping review of disability employment research in the construction industry: Driving social innovation through more inclusive pathways to employment opportunity.” Buildings 12 (12): 2196. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122196.

Baker, M., M. Ali, and E. French. 2023. “Investigating how women leaders and managers support other women’s entrance and advancement in construction and engineering.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 149 (2): 04022166. https://doi.org/10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-12399.

Baker, M., E. French, and M. Ali. 2021. “Insights into ineffectiveness of gender equality and diversity initiatives in project-based organizations.” J. Manage. Eng. 37 (3): 04021013. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000893.

Barreto, U., E. Pellicer, A. Carrión, and C. Torres-Machi. 2017. “Barriers to the professional development of qualified women in the Peruvian construction industry.” J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 143 (4): 05017002. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EI.1943-5541.0000331.

Bryce, T., H. Far, and A. Gardner. 2019. “Barriers to career advancement for female engineers in Australia’s civil construction industry and recommended solutions.” Aust. J. Civ. Eng. 17 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/14488353.2019.1578055.

Burgoon, J., E. Arneson, J. Elliott, and R. Valdes-Vasquez. 2021. “Visual ethnographic evaluation of construction programs at public universities: Who is valued in construction education?” J. Manage. Eng. 37 (4): 04021025. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000899.

Cao, J., C. Liu, G. Wu, X. Zhao, and Z. Jiang. 2020. “Work–family conflict and job outcomes for construction professionals: The mediating role of affective organizational commitment.” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (4): 1443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041443.

Carnemolla, P., and N. Galea. 2021. “Why Australian female high school students do not choose construction as a career: A qualitative investigation into value beliefs about the construction industry.” J. Eng. Educ. 110 (4): 819–839. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20428.

Chan, P. 2013. “Queer eye on a ‘straight’ life: Deconstructing masculinities in construction.” Construct. Manage. Econ. 31 (8): 816–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2013.832028.

China National Bureau of Statistics. 2018. “China statistical yearbook: Chapter 4: Employment and wages.” Accessed October 25, 2023. https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2018/indexeh.htm.

Choi, B., S. Hwang, and S. Lee. 2017. “What drives construction workers’ acceptance of wearable technologies in the workplace? Indoor localization and wearable health devices for occupational safety and health.” Autom. Constr. 84 (Mar): 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2017.08.005.

English, J., and P. Bowen. 2012. “Overcoming potential risks to females employed in the South African construction industry.” Int. J. Constr. Manage. 12 (1): 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2012.10773183.

English, J., and P. Hay. 2015. “Black South African women in construction: Cues for success.” J. Eng. Des. Technol. 13 (1): 144–164. https://doi.org/10.1108/jedt-06-2013-0043.

Erfani, A., P. Hickey, and Q. Cui. 2023. “Likeability versus competence dilemma: Text mining approach using LinkedIn data.” J. Manage. Eng. 39 (3): 04023013. https://doi.org/10.1061/JMENEA.MEENG-5213.

Forman, J., and L. Damschroder. 2007. “Qualitative content analysis.” In Empirical methods for bioethics: A primer, 39–62. Leeds, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Francis, V., and E. Michielsens. 2021. “Exclusion and inclusion in the Australian AEC industry and its significance for women and their organizations.” J. Manage. Eng. 37 (5): 04021051. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000929.

Galea, N., A. Powell, M. Loosemore, and L. Chappell. 2015. “Designing robust and revisable policies for gender equality: Lessons from the Australian construction industry.” Construct. Manage. Econ. 33 (5): 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2015.1042887.

George, M., and M. Loosemore. 2019. “Site operatives’ attitudes towards traditional masculinity ideology in the Australian construction industry.” Construct. Manage. Econ. 37 (8): 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2018.1535713.

Hasan, A., A. Ghosh, M. Mahmood, and M. Thaheem. 2021. “Scientometric review of the twenty-first century research on women in construction.” J. Manage. Eng. 37 (3): 04021004. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000887.

Hasan, A., and I. Kamardeen. 2022. “Occupational health and safety barriers for gender diversity in the Australian construction industry.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 148 (9): 04022100. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002352.

Hernandez-Nicolas, C., J. Martin-Ugedo, and A. Minguez-Vera. 2022. “Women CEOs and firm performance in the construction industry: Evidence from Spain.” Eng. Constr. Archit. Manage. 29 (4): 829–844. https://doi.org/10.1108/ecam-09-2020-0701.

Hickey, P., and Q. Cui. 2020. “Gender diversity in US construction industry leaders.” J. Manage. Eng. 36 (5): 04020069. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000838.

Hickey, P., A. Erfani, and Q. Cui. 2022. “Use of LinkedIn data and machine learning to analyze gender differences in construction career paths.” J. Manage. Eng. 38 (6): 04022060. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0001087.

Jang, H., H. Woo, and I. Lee. 2020. “Effects of self-compassion and social support on lesbian, gay, and bisexual college students’ positive identity and career decision-making.” J. Couns. Dev. 98 (4): 402–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12342.

Johari, S., and K. Jha. 2021. “Exploring the relationship between construction workers’ communication skills and their productivity.” J. Manage. Eng. 37 (3): 04021009. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000904.

Karakhan, A., J. Gambatese, and D. Simmons. 2020. “Development of assessment tool for workforce sustainability.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 146 (2): 04019111. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)co.1943-7862.0001794.

Karakhan, A., J. Gambatese, D. Simmons, and A. Al-Bayati. 2021. “Identifying pertinent indicators for assessing and fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion of the construction workforce.” J. Manage. Eng. 37 (2): 04020114. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000885.

Karakhan, A., C. Nnaji, J. Gambatese, and D. Simmons. 2023. “Best practice strategies for workforce development and sustainability in construction.” Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 28 (1): 04022058. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)sc.1943-5576.0000746.

Keegan, C. 2021. “‘Black workers matter’: Black labor geographies and uneven redevelopment in post-Katrina New Orleans.” Urban Geogr. 42 (3): 340–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1712121.

Keen, J., and A. Salvatorelli. 2016. “Discrepancies between female student perception and reality of the engineering industry.” J. Archit. Eng. 22 (3): 04016011. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)AE.1943-5568.0000221.

Keku, D., F. Paige, T. Shealy, and A. Godwin. 2021. “Recognizing differences in underrepresented civil engineering students’ career satisfaction expectations and college experiences.” J. Manage. Eng. 37 (4): 04021034. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000902.

Kim, A., and D. Arditi. 2010. “Performance of minority firms providing construction management services in the US transportation sector.” Construct. Manage. Econ. 28 (8): 839–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2010.483331.

Kongchasing, N., and G. Sua-iam. 2022. “The main issue working with migrant construction labor: A case study in Thailand.” Eng. Constr. Archit. Manage. 29 (4): 1715–1730. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-05-2020-0376.

Ling, F., M. Dulaimi, and M. Chua. 2013. “Strategies for managing migrant construction workers from China, India, and the Philippines.” J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 139 (1): 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EI.1943-5541.0000124.

Loosemore, M., F. Daniele, and B. Lim. 2020. “Integrating ex-offenders into the Australian construction industry.” Construct. Manage. Econ. 38 (10): 877–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2019.1674449.

Loosemore, M., and B. Lim. 2016. “Intra-organisational injustice in the construction industry.” Eng. Constr. Archit. Manage. 23 (4): 428–447. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-01-2015-0005.

Lu, S., and M. Sexton. 2010. “Career journeys and turning points of senior female managers in small construction firms.” Construct. Manage. Econ. 28 (2): 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190903280450.

Manesh, S. N., J. Choi, B. Shrestha, J. Lim, and P. Shrestha. 2020. “Spatial analysis of the gender wage gap in architecture, civil engineering, and construction occupations in the United States.” J. Manage. Eng. 36 (4): 04020023. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)me.1943-5479.0000780.

Martins, L., K. Bowsher, S. Eley, and G. Hazlehurst. 2011. “Delivering London 2012: Workforce diversity and skills.” Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Civ. Eng. 164 (5): 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1680/cien.2011.164.5.40.

Naoum, S. G., J. Harris, J. Rizzuto, and C. Egbu. 2020. “Gender in the construction industry: Literature review and comparative survey of men’s and women’s perceptions in UK construction consultancies.” J. Manage. Eng. 36 (2): 04019042. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000731.

Navarro-Astor, E., M. Roman-Onsalo, and M. Infante-Perea. 2017. “Women’s career development in the construction industry across 15 years: Main barriers.” J. Manage. Eng. 15 (2): 199–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/jedt-07-2016-0046.

Oo, B., B. Lim, and S. Feng. 2020. “Early career women in construction: Are their career expectations being met?” Construct. Manage. Econ. 20 (3): 56. https://doi.org/10.5130/ajceb.v20i3.6867.

Oo, B., T. Lim, and Y. Zhang. 2021. “Women workforce in construction during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and strategies.” Constr. Econ. Build. 21 (4): 38–59. https://doi.org/10.5130/ajceb.v21i4.7643.

Page, M. J., et al. 2021. “The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews.” BMJ 372 (Apr): n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Perrenoud, A., B. Bigelow, and E. Perkins. 2020. “Advancing women in construction: Gender differences in attraction and retention factors with managers in the electrical construction industry.” J. Manage. Eng. 36 (5): 04020043. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000808.

Petrini, E., and A. Wettergren. 2022. “Organising outsourced workers in UK’s new trade unionism—Emotions, protest, and collective identity.” Social Mov. Stud. 22 (4): 513–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2022.2054795.

Powell, A., and K. Sang. 2013. “Equality, diversity and inclusion in the construction industry.” Construct. Manage. Econ. 31 (8): 795–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2013.837263.

Regis, M. F., E. P. V. Alberte, D. S. Lima, and R. L. S. Freitas. 2019. “Women in construction: Shortcomings, difficulties, and good practices.” Eng. Constr. Archit. Manage. 26 (11): 2535–2549. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-09-2018-0425.

Roelofs, C., L. Sprague-Martinez, M. Brunette, and L. Azaroff. 2011. “A qualitative investigation of Hispanic construction worker perspectives on factors impacting worksite safety and risk.” Environ. Health 10 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-10-84.

Rosa, J. E., C. K. H. Hon, B. Xia, and F. Lamari. 2017. “Challenges, success factors and strategies for women’s career development in the Australian construction industry.” Constr. Econ. Build. 17 (3): 27–46. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v17i3.5520.