Stakeholder Dynamics: Rethinking Roles and Responsibilities in User-Pay Transport PPP Projects

Publication: Journal of Construction Engineering and Management

Volume 150, Issue 8

Abstract

Public–private partnership (PPP) stakeholders have gained traction for their potential to create long-term value. Extant literature emphasizes the importance of suitable stakeholder management strategies, yet the analysis of such strategies has traditionally been conducted from the viewpoint of the responsible parties (i.e., the PPP consortium and the contracting agency) because these are the stakeholders in charge of developing the project and delivering its much-expected benefits. While extant literature often focuses on the interests of either responsible stakeholders or impacted stakeholders, this study addresses the critical but underexplored dynamics involving the wide arrangement of responsible, impacted, and interested stakeholders encompassing diverse groups, such as local communities, interest groups, advisors, local governments, users, and debt providers, who interact and shape project outcomes. Drawing lessons from a multiple-case study involving two mature toll road markets composed of 49 projects, this research reveals the main stakeholders’ issues at three different levels: institutional, organizational, and project. To address these challenges, a relational governance model is proposed where each identified stakeholder should play a specific role in key decisions made in specific project phases. This study provides insights into stakeholder dynamics in user-pay transport PPPs, offering solutions for enhanced engagement and project outcomes. This research offers relevant theoretical contributions to rethinking the roles of impacted and interested stakeholders in PPPs, and these insights have practical implications for improving stakeholder engagement, risk management, and project outcomes in user-pay transportation PPPs.

Introduction

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) in user-pay transport infrastructure have gained significant attention due to their potential for long-term value creation (Castelblanco et al. 2024). These partnerships aim to deliver benefits for stakeholders involved in these projects, including the private and public sectors (Guevara et al. 2024). The benefits may include multiple considerations from financial (e.g., cost efficiencies, revenue generation, and financial gains), social (e.g., traffic benefits and travel time reductions), environmental (e.g., ecological, waste management, greenhouse gas emissions, and pollution issues), economic (e.g., job creation, improved communications, business benefits, fiscal pressure reduction), and operational (e.g., design and construction innovations and resource and skill complementarities) dimensions (Erk et al. 2023; Martinsuo et al. 2019).

Given the size of the financial investments and long-term expectations associated with the delivery of user-pay PPPs for transportation infrastructure, these projects are influenced by significant and multifaceted interests and necessitate the involvement of multiple stakeholders (Nikulina et al. 2022). Academic and industry literature emphasizes the importance of suitable stakeholder management strategies (Francisco de Oliveira and Rabechini 2019; Di Maddaloni and Davis 2018). However, the analysis of such strategies has traditionally been conducted from the viewpoint of the responsible parties (i.e., the PPP consortium and the contracting agency) because these are the stakeholders in charge of developing the project and delivering its much-expected benefits (Liu et al. 2022). Consequently, most of the existing literature seemingly provides a clear but incomplete picture of the stakeholder management dynamics related to user-pay PPP development.

This is somewhat surprising because researchers in other infrastructure-related domains emphasize that large and complex projects are commonly characterized as vulnerable to actions exerted by impacted (e.g., local communities, land owners, and project users) and interested stakeholders (e.g., political and environmental activities, nongovernmental organizations, and chambers of commerce) due to not having sufficient social support, which can represent reputation damages, delays, and cost overruns (Derakhshan et al. 2019a; Shen et al. 2021). Building on that, scholars have started to explore alternative approaches to traditional stakeholder theory to incorporate topics associated with legitimacy, benefit realization, project value, and stakeholder management practices within their analyses. Such motivation is evidenced by an increment in the number of publications focused on such themes within large-scale infrastructure initiatives such as megaprojects and authority-pay PPPs (Li et al. 2023; Musenero et al. 2023; Winata and Gultom 2023).

Considering that user-pay PPPs exhibit multiple similarities to other large-scale infrastructure delivery approaches, it is also surprising how little research evidence exists on how user-pay PPPs have underperformed in terms of managing impacted and interested stakeholder expectations when it comes to delivering promised societal benefits and achieving suitable public support. Examples of how responsible stakeholders have failed to create more inclusive environments and how these failures have played a role in other managerial difficulties are not rare in industrialized jurisdictions. In California’s State Route 91 (SR-91) project, the local communities that initially supported the project started to perceive the toll charges as excessive, coupled with concerns about profits for the concessionaire, which was further fueled by a decline in service levels due to unexpectedly high traffic (Engel et al. 2020). Ultimately, this triggered the early termination of the project because the special purpose vehicle (SPV) was unwilling to renegotiate terms. In Virginia’s Elizabeth River Crossings (ERC) project, public opposition and objections led to six renegotiations between 2012 and 2017, which translated into delays in tolling, lower toll fees and increments, and toll removal (Ghadimi 2017). Although the ERC opened in 2017, the contracting authority had to increase its original contribution by more than USD 270 million and the concessionaire had to assume annual losses of approximately USD 500,000 (Gifford et al. 2023).

In developing economies, the Chilean and Colombian experiences show that stakeholder dissatisfaction may take years of slowly brewing, but there could be very violent explosions. The 2019 protests in Santiago, Chile exhibited deep discontent with the service fee payment strategy implemented for the city’s interurban toll roads. This resulted in the national government being forced to reduce toll fee increases to 0% in real terms (Charney et al. 2021). In Colombia, conversely, the pandemic forced multiple renegotiations in most of the country’s toll roads in 2020, and high inflation rates in 2022 motivated the national government to freeze toll increments in 2023 to prevent protests and social discontent (Guevara et al. 2024; Rojas et al. 2023).

Three main considerations justify the necessity to study the dynamics between responsible and interested/impacted stakeholders in user-pay transport PPPs: the growing literature on stakeholder management for megaprojects and authority-pay PPPs, the similarities between such large-scale initiatives and user-pay PPPs, and the very limited research evidence on the relationship between stakeholder interactions and tolling policy. Recently, a constant increase of studies focused on better understanding the intricacies of incorporating communities’ requirements and responding to public expectations (Gil 2023; Kier et al. 2023; Zhang and Leiringer 2023). However, most of these studies examine experiences in jurisdictions in which projects do not incorporate service fees from users across their life cycle.

Regarding similarities between user-pay transport PPPs and other large-scale initiatives when it comes to managing stakeholder interests, prior research shows that concerns from impacted and interested parties revolve around issues mainly associated with scope and environmental impacts (Kivilä et al. 2017; Ma et al. 2020). Although these are two relevant issues in any large-scale project, the relationship between financing and funding mechanisms and their connection with stakeholder mechanisms remains largely unexplored (Chung et al. 2023; Erk et al. 2023; Kroh and Schultz 2023). This, for user-pay transport PPPs, leads to the necessity to study stakeholder interplays within a context in which toll tariffs exert a profound influence on how projects are shaped, developed, and operated.

The main goal of this study is to analyze the stakeholders’ dynamics in user-pay transport PPPs by examining a diverse sample of projects within the context of mature toll road markets. Specifically, this study focuses on the latest toll road PPP national programs in two mature toll road markets. By adopting a stakeholder perspective and considering the entire life cycle of the projects, the aim is to provide a comprehensive analysis of the interactions among responsible, impacted, and interested stakeholders.

By conducting this analysis, the authors seek to enhance the understanding of stakeholder dynamics in user-pay transport infrastructure PPPs and contribute valuable insights to stakeholder management practices. Ultimately, the findings can inform the development of effective strategies and policies that secure an adequate and sustainable PPP implementation.

Literature Review

PPP Stakeholders

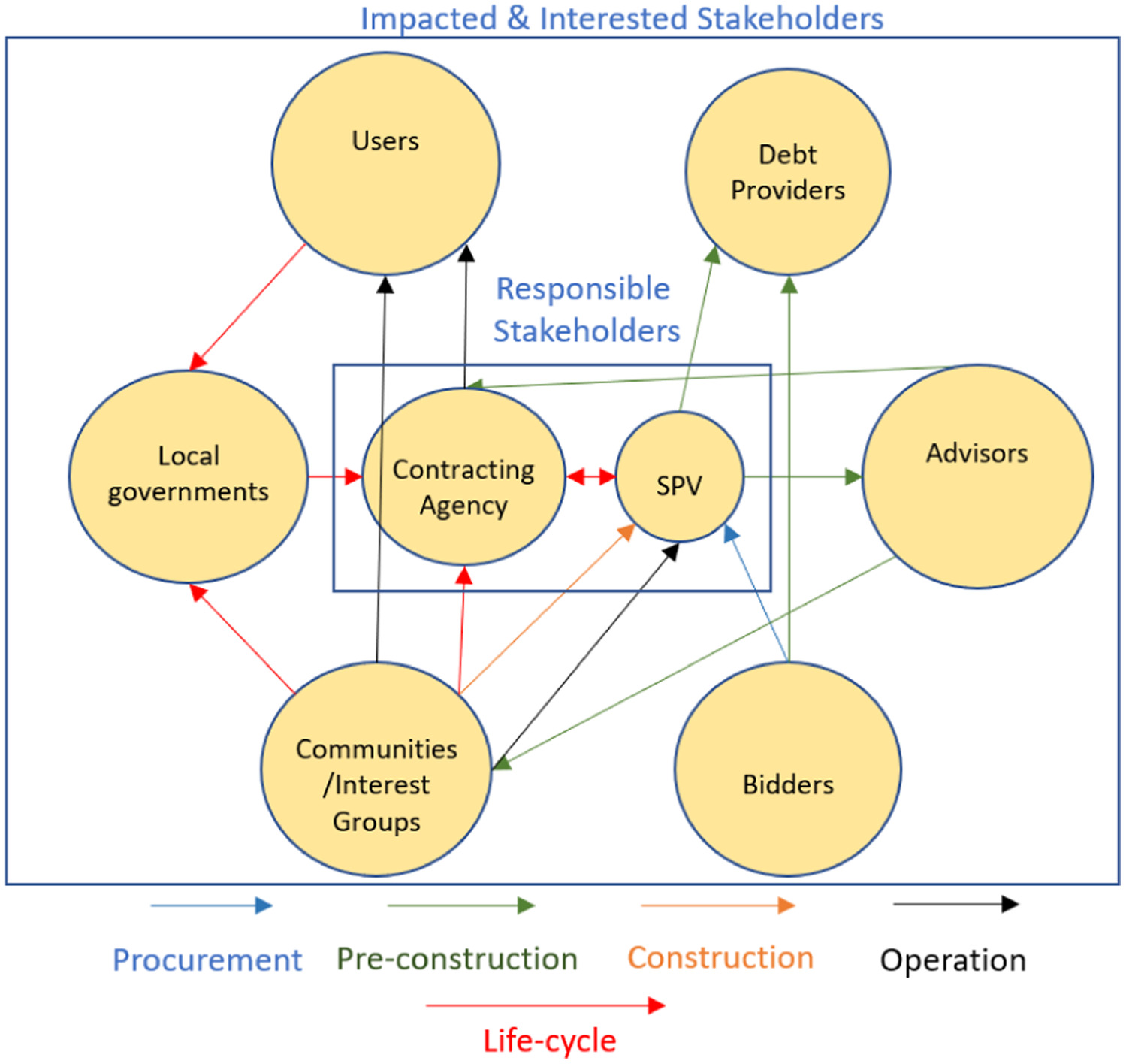

This study employed a stakeholder classification framework that distinguishes between impacted, responsible, and interested stakeholders, considering the various categorizations found in previous literature (Mostafa and El-Gohary 2014). Responsible stakeholders encompass both the public and private parties involved in the PPP because they bear the primary responsibility for its procurement and development (Mostafa and El-Gohary 2014). Interested stakeholders are individuals or organizations that actively provide opinions and participate in the project, such as environmental advisors and consultants, lenders, bidders, and local governments. And impacted stakeholders are organizations or individuals who are affected by the performance of the PPP in a direct way, including project users and local communities.

Interested stakeholders typically comprise organizations that operate beyond the local level and can exert influence at international, national, and regional scales (Mostafa and El-Gohary 2014). In contrast, impacted stakeholders are primarily individuals who maintain continuous and localized interactions with the project throughout its life cycle (Castelblanco et al. 2022b).

The roles of interested, responsible, and impacted stakeholders are transformed throughout the PPP life-cycle phases of shaping, implementation, and operation. The shaping phase encompasses initial activities, such as project conceptualization, contracting, procurement, and planning (Guevara et al. 2020). During this phase, the public sector plays a leading role in defining the project scope and selecting the concessionaire. The procurement process involves the participation of various consortiums competing to become the selected concessionaire (De Clerck and Demeulemeester 2016; El Kawam et al. 2024). Once the shaping phase nears completion, the concessionaire is chosen (Khallaf et al. 2024; Salazar et al. 2024). At this stage, advisors hired by the concessionaire become crucial in obtaining permits, including environmental licenses, and conducting social consultations with local communities (Khan et al. 2018). Additionally, the concessionaire interacts with potential debt providers, which require comprehensive information to assess risk exposure (Kumar et al. 2021).

The implementation phase marks a shift in the roles and responsibilities, with the concessionaire assuming greater prominence over the public sector (South et al. 2018). The concessionaire, acting as a special purpose vehicle, oversees detailed engineering and construction activities (Dewulf and Garvin 2020). During the implementation there is an increased interaction between the impacted stakeholders and the SPV. Potential conflicts may arise between these stakeholders, often necessitating the involvement of local governments as intermediaries to facilitate communication and address concerns. Furthermore, users of the infrastructure may experience travel delays and disruptions due to ongoing construction, which becomes a critical issue for their satisfaction and support.

In the operation phase, the public sector’s role transitions to primarily monitoring the service levels, while the SPV assumes a more prominent and controlling position (South et al. 2018). Project users and local communities that integrate the impacted stakeholders become particularly sensitive to changes in service levels and toll rates (Levitt et al. 2009). As toll rates increase, users’ perception of the affordability of fees may decrease, potentially leading to social opposition and concerns about the project’s social value (Biziorek et al. 2024). This phase becomes crucial for managing stakeholder perceptions and maintaining the legitimacy of the PPP as the realization of promised benefits becomes critical in shaping stakeholder attitudes and support (Boyer 2019).

Impacted Stakeholders in User-Pay PPPs

The enormous impact of megaprojects triggers significant challenges related to pending social concerns and enhancing social benefits (Shen et al. 2021; Tariq and Zhang 2021). These challenges are exacerbated in user-pay PPPs, where the users will permanently be charged for the use of the services provided (Castelblanco et al. 2023). The fragile sustainability of these projects relies on social legitimacy: social appropriation and desirability of projects by communities and local users (Berrone et al. 2019; Castelblanco and Guevara 2022; Montalbán-Domingo et al. 2018).

Although interested stakeholders are primarily formal entities such as chambers of commerce, nongovernmental organizations, and environmental activists with recognized bargaining power, the role of impacted stakeholders has been traditionally underestimated due to the misconception that these stakeholders, regardless of their utmost interests in the project, are not able to act collectively and have no relevant bargaining power (Derakhshan et al. 2019a). However, impacted stakeholders have demonstrated an increasing involvement and awareness seeking to influence the projects and question multiple aspects related to the social benefits provided, the environmental impact, and revenue streams going from them to the SPV (Castelblanco et al. 2023; Cruz-Castro et al. 2024). This increasing relevance of the impacted stakeholders’ role comes from their expectations of the project to ensure and protect their social rights considering that the government has significantly delegated its functions to the SPV for providing specific public services (Kivleniece and Quelin 2012).

Impacted stakeholders have proved to be able to restrain private interests, especially in user-pay PPPs due to the significant apprehension about the fact that the SPV may increase its profitability based on user revenues (Rufín and Rivera-santos 2012). Moreover, impacted stakeholders judge not only the legality of user-pay PPPs but also their legitimacy in terms of the extent the project meets society-shared norms and values (Charney et al. 2021). These challenges are reflected by the increase in social activism opposing the projects and, consequently, a diminishing public endorsement of user-pay PPPs (Kivleniece and Quelin 2012). Social activism is expressed through threatened access to resources and, more importantly, unofficial punishment against the SPV and the project, such as stigmatization, loss of reputation, stakeholder pressure, negative press coverage, boycotts, and public shaming (Castelblanco et al. 2023).

A prominent example of the potential significance of the impacted stakeholders’ role is the Cochabamba water project in Bolivia. In this project, the public perception that Suez (one of the biggest private water operators globally) was charging excessive connection costs while the network expansion remained insufficient led to massive protests, resulting in early termination of the project and the company’s departure with significant reputational and financial losses (Clark and Hakim 2019). This example also highlights the likelihood of impacted stakeholders considering user-pay PPPs as projects motivated by self-interest rather than the public interest.

Research Trends in PPP Stakeholders

Stakeholders garnered considerable attention in the PPP scholarly discourse, reflecting a growing recognition of its significance since the early 2000s (Innes and Booher 2004). Overall, researchers have focused on specific stakeholders’ research trends related to enhancing PPP legitimacy, conflicts, early involvement, and adversarial relationships as follows.

Previous research emphasizes that community and interest groups’ involvement in PPPs contributes to enhanced legitimacy and political support for projects (Boyer 2019). When these stakeholders perceive their concerns are acknowledged and addressed, legitimacy increases, fostering greater support (Francisco de Oliveira and Rabechini 2019; Gil 2023; Kroh and Schultz 2023; Herian et al. 2012). This in turn can result in increased and sustained support for the initiative over the long term (Charney et al. 2021; Witz et al. 2021). Extant literature highlights that communities, when involved, gain a deeper comprehension regarding the unique challenges, problems, and trade-offs associated with a project (Kier et al. 2023; Li et al. 2023). This enhanced understanding empowers stakeholders to provide practical input and contribute to the convergence of issues toward feasible solutions (Shen et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2022). Additionally, this increased understanding enables the public to scrutinize projects, identify violations, apply community pressure, and enforce laws to limit corruption (Kroh and Schultz 2023; Witz et al. 2021).

Early community involvement is frequently cited as a crucial factor in achieving high-quality project outcomes (Kier et al. 2023; Nikulina et al. 2022). Reed (2008) stresses the importance of early involvement and advocates for flexibility when early engagement is not practical. Without such flexibility, local communities may become passive participants, realizing their involvement only after key decisions have been finalized (Charney et al. 2021; Musenero et al. 2023).

Numerous scholars argue that local community and interest group involvement yields various benefits, including building mutual trust, mitigating fears and antagonism toward accountable parties, and promoting more successful results (Nederhand and Klijn 2019; Witz et al. 2021). The inclusivity and deliberative nature of community contributions are highlighted as factors that maximize the benefits of participation (Gil 2023). Furthermore, community involvement and consideration of its recommendations enhance project acceptance, mitigate tensions, and improve overall project efficacy (Erk et al. 2023; Yang et al. 2022).

Community involvement is recognized as a mechanism for preventing antagonistic relations and diminishing disputes through the establishment of a shared platform for stakeholder collaboration (Nikulina et al. 2022; Shen et al. 2021). This is achieved through the establishment of trust and mutual appreciation of the legitimacy of one another’s viewpoints.

In contrast, challenges and conditions under which community involvement may be inefficient, ineffective, or disadvantageous are acknowledged (Shen et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2022). Conditions include stakeholders’ reluctance to participate, highly technical subjects within interest groups, or communities not recognizing an issue as relevant. Stakeholder involvement methods may sometimes become a procedural formality rather than a genuine process (Heikkila and Isett 2007; Castelblanco et al. 2023).

Jolley (2007) provides a comparison of common community involvement methods, including citizen surveys, public hearings, stakeholder interviews, and public deliberations. The influence, potential for dialogue, and levels of engagement of some of these approaches were analyzed by Kroh and Schultz (2023). Public deliberations, while requiring higher commitment and cost, provide a significant chance for comprehensive and transparent dialogue, which is crucial for meaningful involvement.

Despite the acknowledged benefits of community and interest groups’ involvement, the literature reveals a gap in understanding the dynamics and challenges specific to incorporating the complex dynamics when considering the wide arrangement of stakeholders beyond communities such as local governments, project advisors, debt providers, and users, particularly in the context of mature toll road markets, to comprehensively understand stakeholder dynamics and inform effective stakeholder management strategies in PPPs.

Research Design

This paper investigated the stakeholders’ dynamics in user-pay transport PPPs using a qualitative multiple-case study approach. The two toll road PPP programs that were selected for this study were the Fourth Generation Roads Concession plan in Colombia and Chile’s toll road concession scheme. These programs are similar in that they both comprise multiple design-build-finance-operate-maintain PPPs that have reached financial closure. However, they differ in terms of their size, location, and the type of stakeholders involved across their initiatives.

The multiple-case approach was chosen because it allows for the investigation of a broader range of factors that may influence the stakeholders’ dynamics in PPPs (Yin 2018). This approach also provides greater depth of understanding than a single case study (Yin 2003).

The selected projects are listed in Table 1. The data for the research were gathered via interviews with principal stakeholders involved in the two PPP initiatives. The interviews were semistructured and lasted for approximately 1 h each. The data were also supplemented with documents such as contracts, project plans, and financial reports.

| Case | Toll road | Length (km) | Investment (millions of USD) | Financial closure | Contract period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombia | Circunvalar Prosperidad CTG-BQLLA | 147 | 522 | 2016 | 25 |

| Conexión Pacifico 1 | 46 | 1,232 | 2014 | 25 | |

| Perimetral de Oriente Cundinamarca | 153 | 536 | 2014 | 25 | |

| Conexión Pacifico 2 | 98 | 312 | 2014 | 25 | |

| Autopista al Río Magdalena 2 | 114 | 1,370 | 2014 | 25 | |

| Conexión Pacifico 3 | 146 | 646 | 2014 | 25 | |

| IP—Accesos Norte a Bogotá | 62 | 300 | 2019 | 25 | |

| Mulaló-Loboguerrero | 84 | 638 | 2016 | 29 | |

| Honda-Puerto Salgar-Girardot | 190 | 559 | 2016 | 25 | |

| Transversal del Sisga | 137 | 282 | 2018 | 25 | |

| Autopista al Mar 1 | 176 | 713 | 2019 | 30 | |

| Yopal—V/cio | 261 | 1,069 | 2015 | 23 | |

| Autopista al Mar 2 | 246 | 936 | 2019 | 25 | |

| B/manga-B/meja-Yondó | 152 | 683 | 2018 | 29 | |

| Santander de Quilichao-Popayán | 76 | 620 | 2016 | 25 | |

| Cesar-La Guajira | 350 | 134 | 2016 | 34 | |

| Autopista Pasto-Rumichaca | 80 | 788 | 2016 | 25 | |

| Conexión Norte | 146 | 491 | 2014 | 25 | |

| Puerta de Hierro-Palmar de Varela | 203 | 208 | 2019 | 25 | |

| Cúcuta-Pamplona | 63 | 500 | 2020 | 25 | |

| Autovía B/manga-Pamplona | 133 | 203 | 2016 | 25 | |

| Autovía Neiva-Girardot | 193 | 290 | 2015 | 25 | |

| Bolívar-Antioquia | 491 | 604 | 2015 | 34 | |

| V/cio-Chirajara | 86 | 2,064 | 2015 | 30 | |

| APP GICA | 225 | 745 | 2015 | 28 | |

| Malla Vial del Meta | 354 | 482 | 2015 | 30 | |

| Tercer Carril Girardot-Bogotá | 145 | 557 | 2016 | 30 | |

| Vías del NUS | 157 | 369 | 2017 | 30 | |

| Corredor vial Neiva-Mocoa-Santana | 447 | 1,080 | 2016 | 25 | |

| Vía Manizales-Cambao | 256 | 485 | 2015 | 34 | |

| — | 4,563 | 19,438 | — | — | |

| Chile | Segunda Concesión Túnel el Melon | 5 | 125 | 2016 | 15 |

| Concesión Alternativas de Acceso a Iquique | 78 | 159 | 2011 | 32 | |

| Concesión Autopista Concepción—Cabrero | 103 | 344 | 2011 | 35 | |

| Concesión Ruta 5 Tramo La Serena—Vallenar | 187 | 345 | 2012 | 35 | |

| Primera Concesión Rutas del Loa | 133 | 268 | 2013 | 30 | |

| Segunda Concesión Rutas del Loa | 136 | 300 | 2018 | 40 | |

| Segunda Concesión Camino Puchuncavi-Nogales | 27 | 220 | 2016 | 38 | |

| Ruta 43 de la Región de Coquimbo | 86 | 209 | 2013 | 30 | |

| Mejoramiento Ruta Nahuelbuta | 55 | 251 | 2018 | 35 | |

| Mejoramiento Ruta G-21 | 31 | 94 | 2019 | 45 | |

| Puente Industrial | 6 | 248 | 2014 | 41.5 | |

| AVO Príncipe de Gales-El Salto | 9 | 896 | 2014 | 45 | |

| AVO Presidentes-Príncipe Gales | 5 | 805 | 2018 | 45 | |

| Conexión Vial Ruta 78 hasta Ruta 68 | 9 | 250 | 2018 | 45 | |

| Segunda Concesión Camino de la Fruta | 142 | 549 | 2019 | 45 | |

| Segunda Concesión Autopista Santiago—San Antonio, Ruta 78 | 133 | 892 | 2022 | 32 | |

| Segunda Concesión Ruta 5 Tramo Chillan—Collipulli | 169 | 596 | 2023 | 30 | |

| Segunda Concesión Ruta 5 Tramo Talca—Chillan | 195 | 804 | 2021 | 32 | |

| Segunda Concesión Ruta 5 Tramo Serena-Los Vilos | 254 | 497 | 2019 | 30 | |

| — | 1,763 | 7,852 | — | — |

Note: Bold font represents the total values.

Case Study Selection

The Chilean and Colombian toll road PPP programs were selected for this study because they share a number of similarities. Both countries have a common legalistic regime inherited from Spain, and both are medium sized in terms of population in the region. Additionally, both countries have mature PPP markets, with more than 50 user-pay toll roads totaling more than USD 13 billion each. The regulatory frameworks in both countries have also been strengthened in recent years, with new laws enacted in 2010 (Chilean Law 24010) and 2012 (Colombian Law 1508).

The two countries also differ in some important ways. The Colombian 4th generation (4G) toll road PPP program developed after Colombia Law 1508 is larger, with 30 projects totaling almost USD 20 billion. It was designed, implemented, and supported by the Inter-American Development Bank and has experienced struggles in attracting suitable capital investors (Castelblanco et al. 2022b). The Chilean toll road PPP program developed after Chilean Law 24010 is smaller, with 19 projects totaling almost USD 8 billion. It includes some reconcessioned projects, which are toll roads that were originally built under a different PPP model (Castelblanco et al. 2022b). Additionally, this PPP program comprises three urban toll roads in the capital city (Santiago) and interurban roads near Chile’s three largest cities (i.e., Conception, La Serena, and Santiago).

Data Collection

The data for this study were collected through a triangulation of three sources: content analysis of the extant literature, examination of semistructured interviews, and contractual documents and legislation.

A content analysis of the extant literature was conducted to acquire insights into the theoretical framework of dynamics of stakeholders in PPPs. The keywords “build operate transfer,” “public private partnership,” “toll road,” “private finance initiative,” “concession,” “PFI,” “P3,” “PPP,” “BOT,” “stakeholders,” “communities,” and “users” were used to search for relevant articles in the Web of Science database. The initial search resulted in 327 documents from multiple knowledge areas. Refinement of the initial search limited the results to the last 20 years, and 282 manuscripts remained. After this process, unrelated research areas were removed (e.g., evolutionary geography, public environmental health, environmental sciences ecology), and 117 publications were left. Last, the search was refined by including only journal papers published in English, resulting in the retrieval of 95 papers.

The contractual documents and legislation from both PPP programs were examined to acquire insights into the relations, responsibilities, and roles of the stakeholders according to the contractual governance. The contract documents of the 49 projects (which contain more than 350 pages each) were retrieved from the official websites of the public agencies in charge (MOP 2023; CCE 2023).

Semistructured open-ended interviews were conducted with 32 respondents, allowing participants to elaborate on the topics covered and contribute with complementary evidence (Rojas et al. 2020; Yin 2018). The interviewees comprised representatives from academia, concessionaires, public sector institutions, and consultant companies. They were purposely selected according to their involvement and knowledge of the PPP programs. To guarantee diversity of perspectives and avoid bias, the respondents belong to heterogeneous organizational hierarchy levels and functional areas with no less than 5 years of experience. The interview protocol questions were centered on stakeholders’ perceived values, priorities, and expectations in relation to the PPPs and their participation in the decision-making processes. They also inquired in regard to the dispute management mechanisms and the general relationships between stakeholders. The respondents were also asked to discuss the risks that produce the most significant disagreements among the stakeholders as well as the procedures for coordination and communication between them from a life-cycle perspective.

Data Analysis

The authors employed an inductive multistage analysis approach to examine the data (Fig. 1). First, a coding procedure was developed to systematically structure and enhance content analysis of the data from multiple sources. To generate the codes, a comprehensive review of the existing PPPs’ and stakeholders’ body of knowledge was completed, resulting in the identification of primary codes. The analysis led to the identification of first-order codes (Table 2).

| Second-order codes | First-order codes | References | Illustrative quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social involvement pitfalls | Prior consultation | Reeves (2013) | “Communities think that prior consultation entitles them to increase their demands from the concessionaire; therefore they approach the private partner rather than the public sector during the construction phase.” |

| Information exchange | Ortiz-Mendez et al. (2023) and Zhang et al. (2009) | ||

| Community engagement | Castelblanco et al. (2023) | ||

| Timely engagement | Caldwell et al. (2017) | ||

| Collaborative decision-making | Levitt et al. (2009) | ||

| Shared objectives | Castelblanco et al. (2021) | ||

| Optimism bias | El Asmar et al. (2013) | ||

| Bounded rationality and information asymmetry | Awareness of responsible stakeholders | Benítez-Ávila et al. (2018) | “Local communities hold the project accountable for the government’s historical abandonment. False communities emerge out of nowhere. Managing these circumstances is quite challenging.” |

| Community rights | Derakhshan et al. (2019b) | ||

| Social opportunism | Dewulf and Garvin (2020) | ||

| Stakeholder motivations | Benítez-Ávila et al. (2018) | ||

| Power centralization | Levitt et al. (2014) | ||

| Coercion | Biygautane et al. (2019) | ||

| Social value shortcomings | Revenue guarantees | Castelblanco et al. (2020) | “There are no alternative routes to toll roads, which is atypical in comparison with international practice. As a result, if users perceive that tariffs are excessive, they will immediately protest.” |

| Cost overruns | Marcellino et al. (2023) | ||

| Site acquisition risks | Nguyen et al. (2018) | ||

| Social opposition risks | Biziorek et al. (2023) | ||

| Demand risks | Castelblanco et al. (2022a) | ||

| Toll fees | Villalba-Romero and Liyanage (2016b) |

Second, a triangulation approach was applied for examining the cases. This involved recording and transcribing interviews, resulting in more than 50 h of audio recordings and 700 pages of text. The transcribed interviews were then read to create a narrative that highlighted the relevant issues among PPP stakeholders. Additionally, content analysis was carried out on the interviews, contracts, and legislation using NVivo 12, employing the framework of the primary codes. The analysis of the legislation provided insights into the regulatory framework of each PPP program and the envisioned stakeholders roles. The review of contracts enabled the identification of responsibilities, rights, roles, and processes related to stakeholders in each project. The scrutiny of transcripts revealed the actual performance of projects in each country.

Last, after analyzing the data from each project using the primary codes, a hierarchical aggregation procedure was carried out to develop second-order codes inductively. Challenges associated with the participation of social actors in the projects were categorized as social involvement pitfalls, limitations on rationality and information sharing were labeled as bounded rationality and information asymmetry, and issues concerning value creation from the communities’ perspective were named social value shortcomings. The list of codes (first and second order), representative references, and illustrative quotes from the interviews are presented in Table 2.

To ensure internal validation and replicability, a structure grouping technique was devised to establish and validate the codes. The authors independently analyzed the interview transcripts, contractual documents, and legislation using the first-order codes, and any discrepancies between the analysts were discussed until an agreement was reached.

Stakeholders’ Interplay

The analysis of the two national PPP programs revealed three crucial issues related to the interactions among six stakeholders (represented by arrows in Fig. 2) that emerged at various levels: institutional (i.e., social involvement pitfalls), organizational (i.e., stakeholders’ bounded rationality), and project specific (i.e., social value shortcomings) (Table 3). These issues are further discussed in the subsequent subsections.

| Issues | Impacted and interested stakeholders | Level | Causes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social involvement pitfalls | Communities | Institutional | 1.1. Fragmented regulations |

| Advisors | 1.2. Fragmented scope of consultation | ||

| 1.3. Fragmented life-cycle approach | |||

| 1.4. Fragmented identification of impacted stakeholders | |||

| 2. Bounded rationality and information asymmetry | Bidders | Organizational | 2.1. Historical conflicts among stakeholders |

| Debt providers | 2.2. Centralization in public sector | ||

| Communities | 2.3. Coercive influence | ||

| 2.4. Opportunistic behavior | |||

| 3. Social value shortcomings | Local governments | Project | 3.1. Excessive tariffs |

| Users | 3.2. Optimistic bias in public sector | ||

| 3.3. Risks supported by toll tariffs | |||

| 3.4. Tariff versus service levels |

Interplay at the Institutional Level: Social Involvement Pitfalls

Effective social involvement plays a crucial role in the successful execution of transport infrastructure projects, particularly in the early phases (Close and Loosemore 2014). It establishes a communication channel between local communities and the responsible stakeholders, shaping the project’s scope and addressing community interests and concerns (Fedorova et al. 2020). The institutional level sets the conditions for social involvement through requirements for social consultation defined in national legal frameworks (Reeves 2013). However, the analysis of both PPP programs revealed significant issues in this process, leading to various impacts.

Within the analyzed national PPP programs, there is a notable regulatory fragmentation regarding prior consultation, resulting in a diverse array of presidential directives, ordinances, rulings, laws, and decrees (Table 4). Consequently, social consultation was conducted based on a fragmented set of regulations, leading to challenges in identifying and involving ethnic, Indigenous, and other local communities. The higher the regulatory fragmentation in social consultation, the weaker the government’s ability to verify and enforce compliance.

| Decade | Chile | Colombia |

|---|---|---|

| 1990s | Law 19253 of 1993: Protection of Indigenous Peoples | Political Constitution of 1991: Article 330: Indigenous Territories |

| Law 19300 of 1994: General Environmental Framework | Law 21 of 1991: Ratification of International Labour Organization Convention 169 | |

| Law 99 of 1993: General Environmental Law | ||

| Sentence SU039 of 1997: Prior Consultation for Ethnic Groups | ||

| Decree 1320 of 1998: Prior Consultation for Natural Resource Exploitation within Afro-Descendant and Indigenous Territories | ||

| 2000s | Supreme Decree 124 of 2009: Ratification of International Labour Organization Convention 169 | Sentence C030 of 2008: Consultation for Ethnic Groups |

| 2010s | Supreme Decree 40 of 2012: Regulation of Environmental Impact Assessment System | Sentence T129 of 2011: Rights to Prior Consultation |

| Instruction for Environmental Impact Assessment System No. 140143 of 2014: Preliminary Analysis of Indigenous Groups | Decree 2613 of 2013: Protocol for Prior Consultation | |

| Supreme Decree 66 of 2014: Implementation of International Labour Organization Convention 169 | Presidential Directive 10 of 2013: Steps to Conduct Prior Consultation | |

| Law 1682 of 2013: Infrastructure Law |

The presence of ethnic minorities further contributes to the fragmentation of the consultation scope. In Colombia, social consultation is mandatory for ethnic minorities such as Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, identified by the Ministry of the Interior in the project’s surrounding area. Conversely, consultation with the remaining impacted communities is not obligatory according to the legal framework but rather dependent on internal procedures within the public authority. As an interviewee from the public sector pointed out: “When rights are turned into privileges for a few communities, it disrupts the relationship with other communities.” To mitigate potential disruptions when ethnic minorities are granted social consultation privileges, it is imperative for responsible stakeholders to proactively enhance nonmandatory prior consultations with the remaining affected communities simultaneously. Although previous literature has explored the influence of communities on projects and organizations (Chung et al. 2023; Derakhshan et al. 2019a; Francisco de Oliveira and Rabechini 2019; Kroh and Schultz 2023; Di Maddaloni and Sabini 2022), this paper complements this perspective by unraveling disruptions among communities derived from heterogeneous consultation privileges and offers a way out: responsible stakeholders should proactively strengthen nonmandatory prior consultations with the remaining affected communities.

In Chile, the Environmental Evaluation Service incorporates community consultation within the environmental licensing process to compensate for the absence of a dedicated social consultation law. The fragmentation of the consultation scope for nonethnic minorities has significant consequences for project legitimacy and value creation because it neglects the involvement of a large proportion of local communities. In Colombia, the Mulaló-Loboguerrero project stands out as having the most significant time delays, amounting to 7 years. These delays can be primarily attributed to the lack of agreements reached between the responsible stakeholders and the ethnic communities. The lack of consensus with these communities during the consultation process, particularly concerning environmental aspects, prevented the National Agency of Environmental Licensing (ANLA) from conceding environmental licensing for a long time. It took several years to resolve this issue, thanks to the involvement of multiple political and social actors who acted as intermediaries between ethnic communities and the responsible stakeholders. The unique status of the consultation process with these communities (rather than other local communities), as outlined in Sentences SU039 of 1997 and C030 of 2008 (Table 4), proved to be of utmost importance in this project.

Social consultation is also fragmented throughout the project’s life cycle. Although it is a mandatory communication mechanism during the early phases, there is a lack of substantial channels for impacted stakeholders to engage with both public and private partners in subsequent phases. Consequently, the public sector delegates the consultation process to the private party (as indicated in Table 5), resulting in the SPV becoming the sole local intermediary between communities and the project site. In Colombia, this issue is exacerbated by the fear of public sector decision makers who anticipate potential investigations by the Attorney General’s Office due to the implications of their decisions, as well as limited funds for some activities. As a result, there is a tendency to transfer responsibilities to the private sector, including communication with communities and land acquisition. Once the bidding process is complete and the SPV is awarded the contract, they become responsible for tasks traditionally handled by the public sector, such as negotiating and acquiring land, as well as conducting public consultations. While land acquisition disputes can strain the relationship with local communities, the SPV is simultaneously required to engage in prior consultations with those same communities. This is exacerbated when the public sector fails to adequately identify properties during planning. For instance, in the Transversal del Sisga project, the initial projection was to purchase only 40 properties, but the actual number ended up being 350.

| Country | Concessionaire’s responsibilities | Public sector’s responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| Colombiaa | “The Social and Environmental Management required to execute the interventions will be the responsibility of the concessionaire, which will complete such tasks, carefully adhering to the assignment of responsibilities and duties outlined in the contractual documents. The concessionaire must undergo consultations with Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities, following the rules set forth by the Applicable Legal Framework.” | “The Agencia Nacional de Infrastructura (ANI) must assign responsibility … to accompany the Concessionaire in consultation with Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities and to coordinate the required actions for conducting and concluding them with the Ministry of the Interior when demanded by law.” |

| Chileb | “The concessionaire is required … to take all necessary actions for the environmental protection and conservation …, and is responsible for the implementation of all the required measures to guarantee optimal territorial and environmental management of the project and adhere with … the environmental standards outlined in the Environmental Qualification Resolution” (CCE 2023). | — |

The fragmentation of the social consultation throughout the project’s life cycle is reflected in the fact that the public sector’s direct involvement with the communities only extends until the bidding process concludes and the contractor is selected. From that point on, it becomes the responsibility of the SPV to manage this role with the communities for the duration of the contract, which usually spans several decades. This fragmentation contradicts the claim of PPPs to adopt a life-cycle integrated approach. In this regard, an interviewee commented: “Once the license is acquired, there is a detachment from the community. The concessionaire no longer prioritizes those residing in the zone.” Furthermore, the public owner’s assessment of service levels for availability payments often neglects the performance of stakeholder involvement. As a result, the intended scope of consultation remains unfulfilled, and responsible stakeholders view the process merely as a procedural requirement rather than a genuine commitment to address community concerns. The Cesar-La Guajira project revealed this misbehavior. This PPP was initiated as a unsolicited proposal (USP) led by a consortium, which ultimately became the sole bidder and won the tendering process. The SPV fulfilled all the legal requirements, including social consultation, during the preconstruction phase. However, despite the consultation being legally completed, unsolved social claims were exacerbated a few months later, leading to the early termination of the project and subsequent compensation to the SPV by the public sector. Previous literature approaching stakeholders’ claims from a life-cycle perspective has primarily concentrated on elucidating the manner and timing of these claims (Martinsuo 2020; Martinsuo et al. 2019). This study builds on this framework, shedding light on the transformations in pivotal roles and responsibilities across the life cycle that contribute to the diminishing nature of stakeholders’ claims once the obligatory consultation concludes during the preconstruction phase.

Another hindrance to social involvement is the fragmented identification of impacted stakeholders, which poses a risk to the legitimate rights of affected individuals and organizations. The diverse nature of these stakeholders, with varying backgrounds and geographic locations sometimes hundreds of kilometers from the project site, presents challenges in their proper identification. Indeed, out of the 49 toll roads analyzed, a significant portion (31) were projects covering more than 100 km each. These projects often simultaneously impacted diverse social stakeholders including urban populations, rural communities, Indigenous groups, and ethnic minorities. Effective stakeholder identification requires the involvement of local governments and multiple public entities. Interestingly, this issue was more pronounced among interviewees from the private sector than the public sector, suggesting that the stakeholders responsible for identification are less aware of the problem. This underperformance manifested in complications related to the prior consultation of a PPP project that had to be postponed for 5 years (i.e., Mulaló-Loboguerrero).

Interplay at the Organizational Level: Bounded Rationality and Information Asymmetry

At the organizational level, the interplay between impacted and interested stakeholders is influenced by issues of opportunism and bounded rationality (Dolla and Laishram 2020). One significant factor contributing to these issues is the negative history between impacted stakeholders and the responsible parties (Amadi et al. 2018). Public sector interviewees have reported that local communities often express grievances regarding historical governmental neglect, which is a common problem in developing countries. As an interviewee exposed: “Local actors, such as oversight groups, have been increasingly engaged [in road PPP projects]. Due to the absence of the government in providing basic services, they aim to utilize road PPPs as a means to demand water supply systems and initiatives beyond the scope of the project.” Moreover, the perception of PPP transportation projects is frequently influenced by how impacted stakeholders have experienced previous PPPs or transportation initiatives (Amadi et al. 2020). Therefore, the historical relationship between the public sector and impacted stakeholders shapes the preconceptions and perceptions of these communities regarding future projects. This issue becomes particularly pronounced when new PPP projects are developed along the same route after the completion of a previous PPP concession period. Some notable examples of social opposition in reconcessions include the Malla Vial del Meta, Autopista Antioquia-Bolivar, and Autopista Chiarajara-Villavicencio projects. These initiatives have faced multiple protests and social activism, stemming from issues that originated in the previous PPP arrangements. Negative past experiences inevitably lead impacted stakeholders to exhibit opportunistic behaviors toward the new project.

In unitary countries like Chile and Colombia, PPP projects are primarily managed by centralized national institutions that lack a local presence. Consequently, proper communication between the contracting authority and the communities is hindered, resulting in increased information asymmetry and bounded rationality. The communities limit the sharing of information during the project shaping phase, impeding the public sector’s ability to adequately plan the project. In addition, local authorities may perceive that transportation megaprojects may not bring significant value to their communities. As a Colombian interviewee pointed out: “The local authorities are not in favor of the [Perimetral de Oriente Cundinamarca] project. It’s challenging to explain to local entities in small cities that this project will benefit them considering that the project’s main goal is to serve Bogota’s mobility.” As a consequence, information asymmetry and bounded rationality affect key actors involved in the preimplementation phase. In Chile, the Concession Ruta 5 Tramo La Serena–Vallena project experienced significant time delays due to the unexpected discovery of an Indigenous cemetery during the construction phase in 2014. Surprisingly, local Indigenous communities were already aware of the existence and potential location of this cemetery. However, due to the lack of meaningful involvement and consultation processes with these communities, their valuable knowledge was not communicated to the public sector during the project planning.

The analysis of the cases revealed that protests and social opposition to the project are considered risks that may be addressed through the use of coercive power. This often leads to the enforcement of protesters’ displacement by the police through the use of violence, further exacerbating distrust between impacted stakeholders and the responsible parties. This happened in 2019 in Chile, when urban toll road PPP projects in Santiago experienced blockades by protesters, leading to confrontations with the police, who resorted to coercive measures (Charney et al. 2021). Similarly, in Colombia, the Santander de Quilichao-Popayán toll road has seen recurring blockades by Indigenous groups, which have been met with police violence on several occasions. Rather than promoting dialogue as a means to resolve differences, contractual terms indicate that the SPV is held accountable for the expenses and delays associated with protesters’ occupation (Table 6). These contractual clauses impede communication between responsible and impacted stakeholders from the early stages of the project. By eroding trust between these stakeholders, the prevailing contractual governance paradigm exacerbates bounded rationality.

| Country | Access to the project corridor lands | Losses caused by third parties |

|---|---|---|

| Chilea | “It shall be the sole Concessionaire’s responsibility to protect the project assets and project site, as well as any cost overruns and delays that may happen during the implementation phase due to the inability to access the project site because of the unauthorized occupation or constructions by third parties, once the delivery of the expropriated area has been completed.” | — |

| Colombiab | “[It is a risk allocated to the concessionaire] the unfavorable effects … due to the invasion of the Project Corridor by third parties, given that the Concessionaire must take the necessary measures established by the Applicable Legal Framework for the protection and defense of the Project Corridor in a timely and proper manner.” | “The detrimental consequences of all damages to the property of the Concessionaire caused by third parties [is a risk assigned to the concessionaire], without limiting its right to demand from third parties the compensation or repair or of the direct or indirect losses when applicable.” |

| “The consequences of partial or complete theft or destruction of the Concessionaire’s equipment, materials, and goods or its subcontractors [is a risk allocated to the concessionaire].” | ||

| “The event liability waivers do not include terrorism, third parties’ malicious acts, civil war, riot, or strike, which are risks that must be under insurance by the Concessionaire.” |

The cases unveiled a consistent pattern of opportunistic behavior exhibited by impacted stakeholders toward PPP transportation projects, resulting in two mechanisms that contribute to cost overruns. The first mechanism occurs during the preimplementation phase, wherein individuals falsely claim to be part of the local communities in order to seek compensation through fraudulent lawsuits against the project. One notable example is the Circunvalar Prosperidad Cartagena-Barranquilla toll road, where multiple people attempted to build on the Virgin’s Marsh zone, claiming to be historical inhabitants of this zone, and seeking compensation through fraudulent lawsuits against the project. The second mechanism emerges during the implementation and operation phases, wherein impacted stakeholders engage in blackmail by threatening protests that disrupt traffic unless they receive additional economic compensations and facilities beyond what was initially established, such as the Bolívar-Antioquia toll road. Ironically, the cost overruns resulting from these opportunistic behaviors by impacted stakeholders are often borne by the stakeholders themselves in user-pay transportation PPPs, perpetuating a reinforcing cycle between social opportunism and toll tariffs. Interviewees in both countries acknowledged the challenge of convincing impacted stakeholders that expanding the project scope ultimately leads to higher contributions from them through taxes or toll tariffs.

Interplay at the Project Level: Social Value Shortcomings

At the project level, the interplay between responsible, impacted, and interested stakeholders is shaped by the tension between positive outcomes achieved through PPPs and the toll tariffs imposed. PPPs are intended to create social value by delivering societal benefits that surpass what either party could achieve independently (Caldwell et al. 2017). However, in user-pay transportation PPPs, the creation of social value must also consider the equilibrium between these benefits and the toll tariffs and taxes paid by society.

The cases examined in both countries revealed that toll tariffs are often driven up by the public sector’s objective to reduce public subsidies for the project. Consequently, toll tariffs have seen annual increases of up to 3.5% after adjusting for inflation in some projects (Castelblanco et al. 2022b). Unbalanced tariff structures have significant political and social implications, eroding public support for the projects (Osei-Kyei and Chan 2017). For example, in Colombia, excessive toll tariffs led to the early termination of one PPP project (Cesar-Guajira) during the preimplementation phase in one of the country’s poorest regions because impacted stakeholders obstructed the installation of toll collection facilities. In Chile, a significant portion of the social movement in 2019 focused on demanding an end to user-pay transportation PPPs, especially in urban toll roads such as AVO Príncipe de Gales-El Salto and AVO Presidentes-Príncipe de Gales. Excessive tariffs erode projects’ social legitimacy and, ultimately, lead to renegotiations that will affect project performance as pointed out by an interviewee: “[The contract stipulated] that a toll booth had to be installed in Functional Unit 1 [of the Pasto-Rumichaca project], but the community consistently opposed it. Differential rates were proposed, but [the communities] did not accept. Finally, in an addendum, the expansion of the road in the Functional Unit 1 section was completely eliminated, and the toll booth was relocated.”

The optimistic bias of the public sector in forecasting toll revenues also negatively impacts the social value of the projects (Chung et al. 2010). Unrealistic revenue forecasts continue to be common due to risk underestimation and the neglect of macroeconomic crises that periodically occur (Villalba-Romero and Liyanage 2016a). Camino de la Madera in Chile and Malla Vial del Meta in Colombia encountered significant decreases in traffic compared to the initial forecasts, resulting in different outcomes for each project. The former had to be terminated early, while the latter required renegotiation of the project scope to adapt to the traffic changes. Consequently, contingency budgets are often insufficient, and long-term demand is overestimated, jeopardizing the project’s financial equilibrium over its life cycle (Carpintero et al. 2013; Ottaviani et al. 2024). As a result, the public sector frequently overestimates revenues and miscalculates the project’s life-cycle costs (Flyvbjerg et al. 2007).

Analysis of the contractual clauses in both countries revealed that several risks that may affect the project’s financial equilibrium can have detrimental effects on users. Risk response mechanisms outlined in the contracts stipulate that certain risks may lead to an extension of the initial concession period or additional increases in user toll tariffs, negatively affecting impacted stakeholders in either case (Table 7). Traffic risk, for instance, is allocated to the public sector in both countries, resulting in higher public subsidies and extending the concession period through mechanisms such as flexible terms or minimum income guarantees. Furthermore, contractual clauses in both countries state that cost overruns resulting from risks allocated wholly or partially to the public sector (e.g., site connections, environmental risks, land acquisition) may be transferred to users through higher toll tariffs.

| Risk | Chilea | Colombiab |

|---|---|---|

| Demand risk | “Revenue and Demand Risks: The risks associated with the uncertainty of the traffic of the Toll Collection Facilities during the operation phase can be distributed through a Minimum Income Guaranteed mechanism.” | “Public Sector’s Principal Responsibilities during the Maintenance and Operation Phase: If the concessionaire has not reached its corresponding Toll Collection Present Value, the gap is determined, and the Agencia Nacional de Infrastructura (ANI) will compensate it in Years 8, 13, and 18. If by the end of the 25th year, the concessionaire has not reached its Toll Collection Present Value, the concession period can be extended until the 29th year.” |

| Toll rate increase | “Suspension of the Contract: If the concessionaire has experienced damages that result in indemnities, it can be rewarded through increases in toll rates, public subsidies, the concession period, or any other factor of the contracts’ regime.” | “Public Sector’s Risks: The detrimental consequences of the project’s Toll Resolution, the incorporation of differential rates in the existing Toll Facilities and/or New Toll Facilities [are allocated to the public sector]. To offset the Value of the Risk Materialization, the Risk Compensation Mechanisms will be employed.” |

| “Mechanism to Increase Rates and Toll Stations: Risk Compensation will be reimbursed to the Concessionaire by increasing the user fees of the toll facilities and/or the development of additional toll facilities to guarantee the Toll Collection Present Value.” |

The imbalance between service levels and toll tariffs also has a negative impact on the social value of projects, particularly in urban toll PPPs. In these projects, congestion tariffs are designed to discourage users from utilizing the roads during peak hours and regulate average speeds during those periods. However, this intended self-balancing mechanism has not significantly influenced users’ choices, leading to the majority of users paying higher prices for subpar service levels. In response to protests and the support of local governments, the national public authority in Chile decided to reduce the tariffs for all urban toll road PPPs including AVO Príncipe de Gales-El Salto, AVO Presidentes-Príncipe de Gales, and Conexión Vial Ruta 78–Ruta 68.

In general, the three types of issues presented in this analysis are interconnected. Social involvement pitfalls trigger bounded rationality and information asymmetry for responsible stakeholders, resulting in inadequate risk analyses and social opportunism. Mutual distrust leads responsible stakeholders to neglect community concerns, viewing them as a source of risk rather than recognizing their role as essential stakeholders contributing to the project’s social value. Consequently, when toll tariffs are defined, impacted stakeholders are not adequately considered, leading to excessive payments and, ultimately, protests and unrest against the project.

Rethinking the Role of Impacted and Interested Stakeholders

To address the identified issues, this section proposes specific adjustments to the role of impacted and interested stakeholders at multiple levels, taking a life-cycle perspective. These stakeholders have the potential to contribute to enhancing the legitimacy and outcomes of toll road PPPs worldwide.

In addition to social consultation, there is a need for relational governance between responsible stakeholders (such as the public and private sectors) and impacted stakeholders (including users and local communities) to overcome fragmented communication, opportunistic behavior, and excessive toll tariffs. The current dyadic contractual governance scheme in PPPs should evolve into a triadic relational governance scheme that actively involves impacted stakeholders in the decision-making process. By including impacted stakeholders within the institutional framework, social value propositions in toll road PPPs can extend beyond the provision of transportation infrastructure. This can be achieved by strengthening the identification of impacted stakeholders, determining their primary interests, developing a mutually agreed communication strategy, and regularly evaluating stakeholder management using appropriate indicators. This triadic relational governance scheme has the potential to reduce the likelihood of time and cost overruns resulting from social opposition.

Local governments play a crucial role in addressing the fragmentation of impacted stakeholders, facilitating a comprehensive identification process and balancing public centralization. In unitary countries like Colombia and Chile, local governments can act as mediators, establishing permanent connections with diverse social organizations and individuals situated near the project site. They can foster continuous communication channels between responsible stakeholders and impacted stakeholders, promoting mutual trust and a shared vision of project goals.

PPP bidders can assume an accountability role to counteract bounded rationality and information asymmetry. Nonpreferred bidders, in particular, can exercise life-cycle accountability during the implementation and operation mediated by the role of lenders. Previous research has highlighted how networks within private companies involved in the PPP market, including SPVs and nonpreferred bidders, are characterized by well-connected actors who exert significant influence over their private partners (Guevara et al. 2022). These links are manifested in tangible connections between companies, where multiple partners within nonpreferred bidders of one PPP have joint ventures or share ownership with the preferred bidder on other PPPs. Such intricate connections mean the performance of the project indirectly impacts nonpreferred bidders in terms of their reputation and their ability to secure private financing for future PPP projects. Therefore, there is a clear incentive for nonpreferred bidders to monitor and advocate for good performance from the SPV because any detrimental impact on the project can have cascading effects on their relationships with lenders and their capacity to participate in future PPP projects. In essence, nonpreferred bidders act as a form of oversight, motivated by their interconnected interests and the potential for future collaborations. Furthermore, this inherent motivation not only fosters accountability but also serves as a safeguard, mitigating adverse outcomes like mistrust and opportunistic actions against the project that are often exhibited by interested stakeholders. This is in contrast to impacted stakeholders who often face challenges in unifying heterogeneous interests among individuals, limiting their interaction with project decision makers. Bidders’ accountability can facilitate access to project-related data by international and national debt lenders, enabling them to make more informed decisions.

During the preimplementation phase of project finance transportation projects, the financial closure process incorporates complementary risk assessments by lenders. Lenders can complement the weaknesses of the public sector by demanding better performance from SPVs in the financial, social, and environmental dimensions of the project. These requirements stem from lenders’ inherent risk aversion and are accepted by the SPV because timely financial closure is crucial to avoid delays in project implementation and secure funds for capital expenditures. Consequently, the probability of various risks occurring can be significantly reduced.

The role of SPV advisors is crucial because they often oversee social consultation processes as part of the environmental impact assessment in the preimplementation phase (Kågström 2016). These advisors plan and execute social consultation processes and propose measures to mitigate potential impacts. They possess expertise in diverse disciplines and technical backgrounds, complementing each other’s knowledge. The SPV should strengthen the role of these consultants beyond obtaining approvals for the social consultation process and environmental licenses. They can provide valuable insights for better risk identification and planning, ultimately leading to improved project performance.

Contributions

This study’s findings carry several contributions for megaprojects’ stakeholders. First, while the complexity of megaprojects is intricately tied to the impact and interplay of a myriad of stakeholders operating at various levels, the existing literature on megaprojects has predominantly concentrated on a limited subset of stakeholders. Gil (2023) stressed the importance of responsible stakeholders in retrospectively distributing value to crucial stakeholders at the project level. Conversely, this study’s findings delve into additional intricate interactions at another level, the organizational one. This research found that local communities articulate grievances stemming from historical governmental neglect and engage in systematic behaviors at the program level. These behaviors involve constraining the sharing of vital information, thereby impacting the risk management efforts of responsible stakeholders.

Second, while Di Maddaloni and Davis (2018) underscored the necessity of stakeholder management at the project level, this study posits that strategies at that level, though essential, are insufficient to meet the needs and expectations of local communities. It is also necessary to address issues at the organizational level, including historical conflicts among stakeholders, centralization in the public sector, and coercive influence. Complementarily, this study recommends addressing fragmentation at the institutional level, encompassing regulations, the scope of consultation, a life-cycle approach, and the identification of stakeholders.

Third, while Witz et al. (2021) established that trust built over time with other stakeholders or organizations serves as an initial reference for legitimacy perception, this research goes further by illustrating that this pattern intensifies in PPPs developed along the same route after the completion of a previous PPP’s concession period. Consequently, the foundation for building trust and legitimacy encompasses not only perceptions of organizations or stakeholders but also past perceptions of the societal value of the project and the historical tariffs paid by users for the services provided. In essence, this research extends Witz et al.’s (2021) concept of contextual organizational and institutional trust to the project level.

Last, while prior literature has predominantly addressed the involvement of a broad spectrum of stakeholders in enhancing megaproject outcomes, certain key actors such as nonpreferred bidders, lenders, and SPV advisors have been overlooked (Gil 2023; Di Maddaloni and Davis 2018; Witz et al. 2021). This study sheds light on the strategic significance of nonpreferred PPP bidders, positioning them as crucial stakeholders to complement the accountability role of impacted stakeholders. These bidders play a vital role in exercising life-cycle accountability during the implementation and operation phases, leveraging their communication ties with the public sector and demonstrating effective control and monitoring capabilities over project outcomes. This proactive accountability role facilitates access to project-related data for international and national debt lenders, empowering them to make more informed decisions. This role stands in contrast to impacted stakeholders who often struggle to unify diverse interests, limiting their interaction with project decision makers. Additionally, lenders assume a pivotal role during the preconstruction phase, complementing the public sector by imposing additional commitments on the SPV in the financial, social, and environmental dimensions of the project to secure financial closure under project finance. These requirements, stemming from lenders’ inherent risk aversion, are accepted by the SPV to prevent delays because timely financial closure is crucial for project implementation and securing funds for capital expenditures. While Ninan et al. (2019) proposed practices to manage external stakeholders’ strategies in megaprojects, this research goes a step further by highlighting the critical role of SPV advisors. They are responsible for planning and executing social consultation processes on behalf of the SPVs as part of the environmental impact assessment while proposing measures to mitigate potential impacts. Understanding the advisors’ role is essential for implementing practices with persuasion and flexibility. Specifically, SPV advisors can enhance their engagement with impacted stakeholders from the preconstruction phase, establishing effective persuasion mechanisms to increase the social legitimacy of the project and foster collaboration between impacted and responsible stakeholders. Persuasion relies on flexibility to incorporate strategic scope enhancements, minimize environmental impact, and enhance the societal value provided by the project, particularly in transportation megaprojects.

Conclusions

This article delved into the dynamics of stakeholders in user-pay transport PPPs through a multiple-case study approach. The analysis revealed three key issues present in the two analyzed PPP programs: (1) social involvement pitfalls, (2) bounded rationality and information asymmetry, and (3) social value shortcomings. These issues stem from underlying causes at the institutional, organizational, and project levels.

In light of these findings, this research puts forward specific adjustments to the roles of impacted and interested stakeholders (including users, communities, advisors, debt providers, bidders, and local governments) from a holistic life-cycle perspective. These stakeholders possess the potential to make substantial contributions to enhancing the outcomes and performance of user-pay transportation PPPs.

A key recommendation centers around the transformation of the existing dyadic contractual governance scheme into a multidimensional relational governance model. By integrating the wide arrangement of impacted and interested stakeholders within the institutional framework, the social value propositions of toll road PPPs can transcend the mere provision of transportation infrastructure. Particularly, local governments emerge as vital facilitators, forging robust communication channels between responsible stakeholders and impacted stakeholders, particularly in unitary countries. This concerted effort is crucial for establishing mutual trust and nurturing a shared vision of the project goals. Complementarily, PPP bidders can assume a pivotal accountability role by facilitating enhanced access to project-related data for debt lenders, thereby augmenting the decision-making process. Lenders, in turn, can complement the weaknesses of the public sector by demanding elevated performance standards from SPVs across the financial, social, and environmental dimensions of the project. It is imperative that the SPV strengthens the role of consultants beyond their traditional purview of obtaining approvals for social consultation processes and environmental licenses. These consultants can become instrumental stakeholders, contributing to better risk identification and planning, ultimately bolstering project performance.

Overall, this study provided valuable insights into the dynamics of stakeholders in user-pay transport PPPs, highlighting key issues and proposing adjustments for enhancing stakeholder engagement and project outcomes. However, further research is needed to delve deeper into this complex field and explore additional dimensions. Future studies could investigate the long-term impacts of the proposed adjustments on the performance and sustainability of user-pay transportation PPPs. Additionally, examining the role of emerging technologies, such as digital platforms and data analytics, in facilitating stakeholder collaboration and decision-making would be beneficial. Furthermore, comparative studies across different regions and contexts can offer valuable insights into the transferability of findings and the effectiveness of various governance models. Last, exploring innovative financing mechanisms and risk-sharing frameworks can contribute to the development of more robust and equitable user-pay transportation PPPs. By continuing to explore these avenues, researchers can make significant contributions to the advancement of theory and practice in the field of construction engineering and management.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice Presidency of Research and Creation’s Publication Fund at Universidad de los Andes for its financial support.

References

Amadi, C., P. Carrillo, and M. Tuuli. 2018. “Stakeholder management in PPP projects: External stakeholders’ perspective.” Built Environ. Project Asset Manage. 8 (4): 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/BEPAM-02-2018-0048.

Amadi, C., P. Carrillo, and M. Tuuli. 2020. “PPP projects: Improvements in stakeholder management.” Eng. Constr. Archit. Manage. 27 (2): 544–560. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-07-2018-0289.

Benítez-Ávila, C., A. Hartmann, G. Dewulf, and J. Henseler. 2018. “Interplay of relational and contractual governance in public-private partnerships: The mediating role of relational norms, trust and partners ’ contribution.” Int. J. Project Manage. 36 (3): 429–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.12.005.

Berrone, P., J. E. Ricart, A. I. Duch, V. Bernardo, J. Salvador, J. P. Peña, and M. R. Planas. 2019. “EASIER: An evaluation model for public-private partnerships contributing to the sustainable development goals.” Sustainable 11 (8): 2339. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082339.

Biygautane, M., C. Neesham, and K. O. Al-Yahya. 2019. “Institutional entrepreneurship and infrastructure public-private partnership (PPP): Unpacking the role of social actors in implementing PPP projects.” Int. J. Project Manage. 37 (1): 192–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2018.12.005.

Biziorek, S., A. De Marco, and G. Castelblanco. 2023. “Public-private partnership national programs through the portfolio perspective: A system dynamics model of the UK PFI/PF2 programs.” In Proc., 39th Annual ARCOM Conf., 1–12. Leeds, UK: Association of Researchers in Construction Management.

Biziorek, S., A. De Marco, J. Guevara, and G. Castelblanco. 2024. “Enhancing the public investment in public-private partnerships using system dynamics modeling.” In Proc., 2023 Winter Simulation Conf. New York: IEEE.

Boyer, E. J. 2019. “How does public participation affect perceptions of public–private partnerships? A citizens’ view on push, pull, and network approaches in PPPs.” Public Manage. Rev. 21 (10): 1464–1485. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1559343.

Caldwell, N. D., J. K. Roehrich, and G. George. 2017. “Social value creation and relational coordination in public-private collaborations.” J. Manage. Stud. 54 (6): 906–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12268.

Carpintero, S., J. M. Vassallo, and A. Sánchez Soliño. 2013. “Dealing with traffic risk in Latin American toll roads.” J. Manage. Eng. 31 (2): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000266.

Castelblanco, G., E. M. Fenoaltea, A. De Marco, P. Demagistris, S. Petruzzi, and D. Zeppegno. 2024. “Combining stakeholder and risk management: Multilayer network analysis for complex megaprojects.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 150 (2): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1061/JCEMD4.COENG-13807.

Castelblanco, G., and J. Guevara. 2022. “Building bridges: Unraveling the missing links between public-private partnerships and sustainable development.” Project Leadersh. Soc. 3 (100059): 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plas.2022.100059.

Castelblanco, G., J. Guevara, and P. Mendez-Gonzalez. 2021. “Sustainability in PPPs: A network analysis.” In Interdisciplinary civil and construction engineering projects, 1–6. Fargo, ND: ISEC Press.

Castelblanco, G., J. Guevara, and P. Mendez-Gonzalez. 2022a. “In the name of the pandemic: A case study of contractual modifications in PPP solicited and unsolicited proposals in COVID-19 times.” In Proc., Construction Research Congress 2022, 50–58. Reston, VA: ASCE.