Navigating Machiavellianism in Construction Projects: Leaders’ Communication Strategies and Employees’ Voice

Publication: Journal of Management in Engineering

Volume 40, Issue 6

Abstract

Construction projects, characterized by their significant budget, time, and resource demands, necessitate effective leadership. Existing research has predominantly focused on identifying ideal leadership styles for construction leaders, often overlooking the impact of “bad” leadership. This paper addresses this gap by exploring Machiavellian leadership within construction projects. Utilizing qualitative methods, 30 interviews with construction organization members were conducted to explore communication strategies employed by Machiavellian leaders and their impact on employee voice in construction organizations. The findings reveal that leader communication strategies are shaped by a combination of their Machiavellian personality, the context of the construction industry, and national culture. Furthermore, the impact of leaders’ communication strategies on employee voice depends on the Machiavellian tendencies of both the leader and the employee. This research offers a nuanced and informed research agenda that aligns with emerging industry needs, bridging the gap between theory and practice in construction project leadership.

Introduction

Construction industry is complex, unpredictable, physically unique, and one of the most dangerous industries in which to work (Harvey et al. 2018; Oswald et al. 2022). Construction workers are expected to work in messy, noisy, dusty conditions, while being exposed to adverse weather conditions (Sherratt 2016). Additionally, leaders in the construction industry face countless challenges (Ofori 2008). Leaders are under pressure to “win work” through competitive tendering processes, and are assessed in terms of the project budget, schedule, and quality (Oswald et al. 2020). In this context, leaders might consequently ignore the psychological well-being of their subordinates (Ahmad et al. 2022), to maximize output, work under tight timelines, and narrow profit margins (Oswald et al. 2020).

Accordingly, in a practical sense, the characteristics of effective leadership behaviors might be different in the construction industry, in relation to other industries (Oswald et al. 2022). Leadership is broadly defined as an “influence process” (Denis et al. 2012), and there is a growing body of leadership research with various perspectives to define the ideal leadership traits, behaviors, and styles for leaders in construction (Simmons et al. 2017; Larsson et al. 2015).

For example, Chan et al. (2014) highlighted that transformational leadership in the construction industry serves as a driver of innovation. This leadership style motivates followers to better perform by nurturing personal values and fostering creative thinking. Oswald et al. (2022) found that behaviors of supervisors in construction sites aligned with the Full-Range Leadership Theory (FRLT), including elements of both transformational and transactional leadership. Alternately, Liu and Chan (2017) suggested that contingent reward leadership is a desirable leadership style for inspiring innovation in construction.

However, evidence suggests that toxic leadership may exist in construction industries leading to detrimental outcomes (Khan and Khan 2022; Toor and Ogunlana 2009). Yet, the implications of toxic leadership, such as tyrannical leadership (Breevaart and de Vries 2021), abusive supervision (Khan and Khan 2022), and other forms of destructive leaderships such as Machiavellian leadership (Ahmad et al. 2022) in this type of setting need further examination.

Machiavellianism is defined as “a strategy of social conduct that involves manipulating others for personal gain, often against the other’s self-interest” (Wilson et al. 1996). The most recent study on Machiavellians in the construction industry, conducted by Ahmad et al. (2022), explored the moderating effect of subordinates’ Machiavellian personality trait on the relationship between tyrannical leadership and supervisor-rated subordinates’ task performance. However, their research exclusively concentrated on the Machiavellianism of employees, neglecting to consider the leaders Machiavellian personality. Research suggests that leader Machiavellianism can cause employee dissatisfaction (Shafer and Simmons 2008), distress (Monaghan et al. 2016), emotional exhaustion, burnout (Stradovnik and Stare 2018; Liyanagamage et al. 2023), turnover, and other negative workplace consequences (Koo and Lee 2022).

The aim of this paper is to explore Machiavellianism in construction projects, including leaders and employees, in an Asian context. Specifically, this study will journey through interview conversations with various actors in construction organizations, to (1) explore Machiavellian leaders’ communication strategies, and (2) examine the impact of leader Machiavellianism, manifested through communication strategies, on employee voice in construction organizations.

This article makes several significant contributions to the existing literature. First, this paper addresses the calls to explore leadership in different environments (Hinkin and Tracey 1994), to understand how leadership can manifest in different ways across different industries (Mesu et al. 2015), and the impact of those leadership styles on project processes (Graham et al. 2020) and employees (Imam 2021). Second, this research contributes to the limited literature on the conversational strategies of Machiavellians (Belschak et al. 2018; Ickes et al. 1986; Walter et al. 2005). Although there is a growing body of literature on Machiavellian leadership (Koo and Lee 2022; Liyanagamage et al. 2023), research purely based on personality traits to understand leadership tends to ignore or does not adequately capture one of the most central features of leadership, that is, communication (de Vries et al. 2010). This research extends previous research by exploring the impact of Machiavellian leader communication strategies on employee voice, particularly silence (Brinsfield 2013; Detert and Burris 2007; Erkutlu and Chafra 2019).

Third, this research addresses the need for an exploration of toxic leadership styles within the construction industry, considering cultural dimensions and examining how these dimensions influence the interactions between leaders and subordinates (Ahmad et al. 2022). Notably, this study contributes to the broader scholarly landscape by extending beyond the predominantly Western-centric research in this area, emphasizing the importance of investigating Machiavellian leadership in the Global South, developing contexts, extreme contexts, and across diverse industry and work settings (Liyanagamage and Fernando 2023). Lastly, by exploring how different approaches to leadership, including toxic styles of leadership, drive or constrain success, this paper aims to promote more informed research agendas that align emerging industry needs with theory and practice (Graham et al. 2020; Omer et al. 2022).

Literature Review

Open, regular, and two-way communication between leaders and employees is critical in the construction industry (Liao et al. 2014; Vredenburgh 2002). Leader-to-employee communication involves the conveyance of safety policies, dissemination of information regarding risks and safety measures, hazard analysis, prevention methods, performance updates, variations, timelines, stakeholder requirements, and other pertinent aspects. Leaders’ commitment to safety communication can motivate employees to work safely (Wen Lim et al. 2018), and safety-specific transformational leadership can lead to group-level safety performance (Cheung and Zhang 2020). Receiving information and feedback from leaders would enable the workers to develop themselves (Michael et al. 2006), while listening to issues and concerns raised by workers would allow leaders to identify potential hazards or deficiencies, which otherwise would have been ignored or gone unnoticed (Olive et al. 2006). Accordingly, leadership communication plays a critical role in the success or failure of construction project (Omer et al. 2022; Zaman et al. 2023). Two-way communication allows for dialogism, which is “talking with people not to them” (Cunliffe and Eriksen 2011). It acknowledges that meaning is created in conversations between people and discourse is in relationship to other people, other conversations, and other perspectives (Hunt et al. 2012). In dialogic conversations, views are shared through back and forth dialogue. The intention is not to manipulate or convince you to agree with my point of view but to create new possibilities (Cunliffe and Eriksen 2011). Dialogue can unify meaning which is “coming to a commonly shared purpose while recognizing the differences” (Cunliffe and Eriksen 2011).

However, not all leaders employ two-way communication strategies. Monologic communication strategies are prominent in traditional conceptualizations of leadership, where leaders are perceived as heroes capable of influencing others. In monologic conversations, leaders have control in the interaction and the leader’s opinions are not contested. The leader also manages the meanings and impressions of conversation, and their views are “fixed” as a common understanding (Bakhtin 2010). Monologic discourse is criticized for being oppressive and silencing other voices (O’Connor and Michaels 2007).

Accordingly, active listening plays an important role in dialogic conversations, to ensure that it does not “drown out another’s voice with nonsemantic arguments” (Bakhtin 1981).

Scholarly investigations into communication within the construction industry have been extensive. For instance, Oswald and Lingard (2019) highlighted the significance of supervisors engaging in open, frequent, and two-way safety-related communication with workers as a pivotal aspect of health and safety leadership in the Australian construction industry. A study conducted in the US construction sector revealed that fostering an environment where workers feel free to communicate openly with supervisors about safety correlates with the adoption of safer work practices (Cigularov et al. 2010). In the Danish construction industry, Kines et al. (2010) found that an increase in the frequency of safety-related discussions between foremen and workers significantly enhances workers’ overall safety compliance. However, a noticeable gap in the literature pertains to the exploration of how different leadership styles, particularly those deemed toxic, such as Machiavellianism, impact leader communication and employee voice within organizations.

Machiavellian Leaders and Communication Strategies

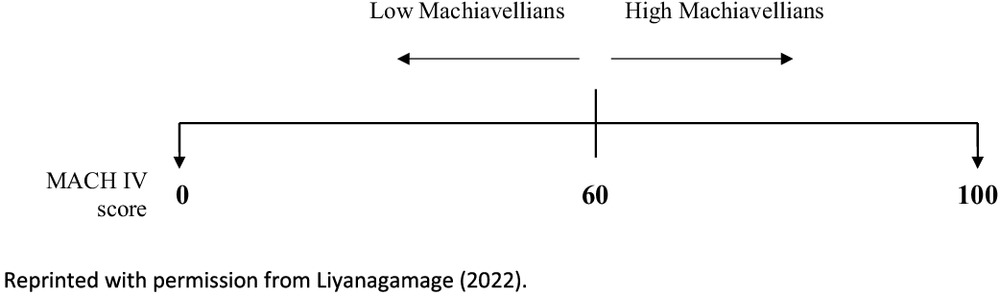

Machiavellian “designate[s] the use of guile, deceit, and opportunism in interpersonal relationships. Traditionally, the ‘Machiavellian’ is someone who views and manipulates others for his own purposes” (Christie 1970). It is a social influence process incorporating the use of politics, power, and expressive behaviors (Christie and Geis 1970). The MACH IV survey, developed by Christie and Geis (1970), is the most widely used survey to measure Machiavellian personality. In this survey, individuals who scored 60 and above were categorized as high Machiavellians (high Machs), while those scoring below 60 were termed low Machiavellians (low Machs). Fig. 1 presents the Machiavellian scale.

High Machs adopt various communication strategies for self-serving reasons. Walter et al. (2005) noted that high Machs’ desire for control is illustrated in their use of communication to uncover information from others to accomplish their self-interested goals and to control others. Belschak et al. (2018) reported that Machiavellianism involves the intentional withholding of information for opportunistic purposes. According to Gemmill and Heisler (1972), when individuals within the organization discern the manipulative tactics employed by high Machs, it often results in a pervasive sense of distrust. Consequently, these individuals may deliberately limit the provision of information, autonomy, and control granted to the Machiavellian figure. In the presence of Machiavellian individuals, others may find themselves compelled to engage in knowledge hiding as a means of self-protection.

High Machs prefer a role that allows them to “call the shots,” and often, in interactions, they are more self-focused, rather than other-focused (Ickes et al. 1986). The focus on self and other is quite evident in conversations, using first-person, second-person, and third-person pronouns. Those who are self-focused are likely to frequently use first-person pronouns, such as I, my, me, mine, and myself. Ickes et al. (1986) reported that high Machs’ use of pronouns demonstrates an assimilative and self-focused approach to social interactions. Interestingly, both high and low Machs indicated frequent use of first-person singular pronouns (that is, I, my, me, mine, and myself), followed by third-person singular pronouns (that is, he, she, and they) in dyadic interactions. They note that this is surprising, given that low Machs are often described as vulnerable, sensitive, truthful, and reluctant to exploit, among other positive characteristics (Nelson and Gilbertson 1991). These findings imply that Machiavellians (both high and low) enjoy talking about themselves, at the cost of others—a stark different from other leadership styles. For example, Cunliffe and Eriksen (2011) propose that morally responsible leaders prioritize open dialogue that recognizes and respects differences, fostering a shared understanding and collaborative decision-making process. However, Ickes et al. (1986) noted that their study on low Machs is limited because their methodology is a simple computer technique, with unstructured counts of pronoun frequency. They suggested that recording naturally ongoing conversation may be more effective.

Existing research on Machiavellianism in leadership conversations is limited and outdated, particularly in temporary project-based industries like construction (Ali et al. 2020; Keegan and Den Hartog 2004). The construction industry’s unique characteristics, marked by high subcontracting and diverse stakeholders collaborating on time-limited tasks, distinguish it (Potter et al. 2018). Construction projects involve multiple stakeholders, potentially leading to disputes stemming from varying perspectives (Illankoon et al. 2019). Leadership in construction is notably task-oriented, prioritizing end goals over means, aligning with Machiavellian principles (Ofori 2008). However, Machiavellians “self-focused” attitude in conversations can particularly influence the functions of construction organizations, where teamwork and effective communication between parties is imperative to successfully navigate complex contractual relationships, partnerships, and informal alliances between stakeholders (Senescu et al. 2013; Cheng et al. 2001). Given the industry’s distinctive nature and leadership structures, it provides an intriguing context for this research. Moreover, the impact of Machiavellian leader communication strategies on employee voice in construction organizations remains unexplored.

Employee Voice

Leadership behaviors and their communication strategies can influence employee voice (Kwak and Shim 2017). Voice is the “discretionary provision of information intended to improve organizational functioning to someone inside an organization with the perceived authority to act, even though such information may challenge and upset the status quo…” (Detert and Burris 2007). Freedom to speak up is imperative for organizational functioning and performance. Many elements influence employees’ decisions to speak up in an organization. For instance, speaking up inherently involves sharing thoughts with a leader or someone considered powerful within the organization (French et al. 1959), with the power to dictate pay, promotions, and job assignments (Dépret and Fiske 1993). Accordingly, leaders become significant to employees’ decisions to speak up. Research identifies that when employees perceive their leader as approachable (Milliken et al. 2003), accessible, and action-taking (Edmondson et al. 2003), they are more likely to speak up. A leader’s traits, behaviors, and attitudes can influence how and why employees decide to speak up or remain silent (Brinsfield 2013; Milliken et al. 2003).

Machiavellian leaders are described as manipulative and controlling, with deceitful intentions to pursue self-interested goals at the cost of others (Belschak et al. 2015; Den Hartog and Belschak 2012). Accordingly, it is not surprising that leader Machiavellianism can cause employee silence (Dahling et al. 2009). Employee silence is the “intentional withholding of information, opinions, suggestions or concerns about potentially important organizational issues” (Erkutlu and Chafra 2019). Employee silence can result in lower organizational commitment and innovation and increase corruption, turnover, and undesirable behaviors (Zaman et al. 2023). There are four classifications for employee silence. Acquiescent silence is “disengaged behavior stimulated by resignation”; quiescent silence is “self-protective behavior stimulated by fear that the consequences of speaking up could be personally unpleasant”; prosocial silence is “withholding work-related ideas, information or opinions with the goal of benefiting other people or organization”; and opportunistic silence is withholding information for opportunistic reasons (Erkutlu and Chafra 2019, p. 325). While current research indicates that Machiavellian leaders may induce employee silence, findings are at an early stage. A more in-depth exploration is needed to explore how the level of Machiavellianism exhibited by both leaders and employees impacts employee silence.

The literature underscores the pivotal role of effective communication in successful construction leadership (Kines et al. 2010; Oswald and Lingard 2019; Zhang et al. 2020); however, it also reveals that dark personality traits can influence leader’s communication strategies (Belschak et al. 2018; Omer et al. 2022), consequently impacting employee voice within organizations (Detert and Burris 2007; Erkutlu and Chafra 2019). Despite a growing body of research on Machiavellian leadership (Koo and Lee 2022; Liyanagamage et al. 2023), there remains a notable scarcity and outdatedness in studies specifically examining the intersection of Machiavellian leadership and communication. Moreover, prior research has primarily focused on either Machiavellian leaders or followers, neglecting various other organizational members within construction sites. The existing body of research is predominantly theoretical or based on empirical data from permanent organizations, lacking insights into the distinctive challenges posed by the construction industry (Ali et al. 2020; Keegan and Den Hartog 2004). Notably, most research in this field is skewed toward a Global West perspective, with limited attention to the Global South and the unique cultural and contextual challenges prevalent in this region (Liyanagamage and Fernando 2023). Empirical evidence suggests distinct perceptions of Machiavellianism in Sri Lanka compared to Western countries (Liyanagamage et al. 2023). For instance, the Machiavellian approach adopted by national leaders in Sri Lankan society and politics has been widely acknowledged (Jayatilleka 2013). Despite these cultural nuances, research on the manifestations of Machiavellianism in organizations and its impact on leaders and employees remains scarce. This research aims to address these gaps by investigating the conversational strategies of Machiavellian leaders in construction sites in Sri Lanka and the implications of these strategies on employee voice.

Methodology

Researchers exploring leadership within the construction industry have advocated for different methodological perspectives, outside of the dominant positivist traditions (Zou et al. 2014). While statistical relationships between leadership, performance, and employee impact have been hypothesized and tested (Ahmad et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2020), understanding what these behaviors look like in practice proves challenging with reliance on self-report surveys. Therefore, alternative research approaches grounded in qualitative methods can be employed to address knowledge gaps encountered by survey-based studies (Oswald et al. 2022).

This study adopts a qualitative research design, leveraging semistructured interviews to delve deeply into Machiavellian leaders’ communication strategies and their implications on employee voice. The research captures interview conversations with diverse organizational actors, providing retrospective accounts and lived experiences of workplace interactions (Tan et al. 2021). In terms of transferability, qualitative research is concerned with the contextual uniqueness and significance of the underlying process in the social world (Bryman 2016). As such, this research is focused on thick descriptions of the context and phenomena in study (Geertz 2008), and attentive to particularizations, rather than generalizations. However, to seek a holistic perspective, this research considers aspects of generalization as well as particularization in the discussion. Despite the limitations of this method, it is essential to emphasize that this research offers a more insightful exploration than previous empirical studies on Machiavellian leadership and communication.

Sample

The study sample consists of various actors involved in leadership processes, including leaders, followers (including employees, sub-contractors, project verifiers), and employees (includes non-followers). This research purposely approached construction projects in the Western Province of Sri Lanka, to gather data from different perspectives as described by various people in various stages of the project (Choi and Schnurr 2014). Large and medium-sized construction firms were identified through a Google search and approached. The final sample consisted of 30 participants from 9 construction firms. The sample size was considered by reflecting on previous studies conducting interviews, for instance, Tan et al. (2021) collected semistructured interviews from 18 leaders and directors, and Assaad et al. (2022) collected semistructured interviews from 11 off-site construction experts and professionals.

A summary of the 30 participants and corresponding organizational information is presented in Table 1. Participants’ names have been anonymized for confidentiality, and pseudonyms are provided. The highest educational qualification is the Charter, held by Thomas, Lance, Stuart, Bernard, and Arthur. This is followed by a master’s degree, Postgraduate degree, Bachelor of Science in Engineering or Civil Engineering, Higher Diploma, Diploma, Vocational qualifications, and Advanced level (i.e., Year 13) and Ordinary level (i.e., Year 11). One participant has education only to Year 9 in high school (i.e., Scott). A majority of the sample identifies as male, only four participants identify as female (i.e., Rachel, Vivian, Claire, and Natalie).

| Name | Organization position | Highest level education qualification | Leader or employee | Age | MACH IV score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | |||||

| Ian | Project Manager | B.Sc. Civil Engineering | Leader | 41 | 60 |

| Travis | Project Engineer | B.Sc. Civil Engineering | Employee | 30 | 71 |

| Patrick | Technical Officer | National Vocational Qualification | Employee | 32 | 49 |

| Anton | Mechanical Foreman | Advanced Level | Employee | 47 | 63 |

| Vivian | Site Supervisor | Diploma in Building Construction | Employee | 28 | 49 |

| Site 2 | |||||

| Thomas | General Manager | Chartered Civil Engineer | Leader | 51 | 54 |

| Brian | Civil Engineer | BSc Civil Engineering | Employee | 31 | 61 |

| Site 3 | |||||

| Lance | Senior Project Manager | Chartered Engineer | Leader | 43 | 53 |

| Tony | Project Coordinator | Master of Business Administration | Leader | 66 | 36 |

| Peter | Quality Assurance Engineer | B.Sc. Civil Engineering | Employee | 31 | 58 |

| Anthony | Foreman | Advanced Level | Employee | 40 | 47 |

| Site 4 | |||||

| Stuart | Project Director | Chartered Engineer | Leader | 53 | 46 |

| Bernard | Engineering Manager | Chartered Engineer | Employee | 34 | 50 |

| Paul | Planning Engineer | B.Sc. Civil Engineering | Employee | 26 | 46 |

| Site 5 | |||||

| Arthur | Project Director | Chartered Engineer | Leader | 52 | 54 |

| Rachel | Planning Engineer | Master of Project Management | Leader | 36 | 49 |

| Mitchell | Civil Engineer | B.Sc. Civil Engineering | Employee | 26 | 56 |

| Brendan | Assistant Engineer | Open University | Employee | 26 | 58 |

| Site 6 | |||||

| Uday | Project Manager | B.Sc. Civil Engineering | Leader | 52 | 70 |

| Claire | Quality Assurance Engineer | B.Sc. Civil Engineering | Employee | 34 | 55 |

| Chris | Civil Engineer | Diploma | Employee | 37 | 54 |

| Mike | Assistant Quantity Surveyor | Higher National Diploma in Quantity Surveying | Employee | 29 | 51 |

| Site 7 | |||||

| Darren | Technical Officer | Diploma in Quantity Surveying | Leader | 26 | 58 |

| Scott | Mason | Year 9 | Employee | 30 | 61 |

| Newey | Contractor-Carpentry | Ordinary Level | Employee | 34 | 51 |

| Site 8 | |||||

| Tod | Site Supervisor | Advanced Level | Leader | 31 | 58 |

| Lee | Technical Officer | Advanced Level | Employee | 57 | 55 |

| Natalie | Technical Officer | Diploma in Engineering | Employee | 35 | 50 |

| Site 9 | |||||

| Daniel | Technical Officer | Year 13 | Leader | 29 | 57 |

| Piyal | Mason | None | Employee | 51 | 51 |

Machiavellian Survey

The last column in Table 1 indicates the Machiavellian personality of the participants. The interview accounts provide a rich perspective of how Machiavellianism manifests in leader communication strategies, while the Machiavellian survey will be an addition to provide knowledge of individual-level personality traits. The intention behind using interview and surveys is for them to complement each other, generating novel insights through data triangulation. Machiavellian personality was tested using the MACH IV survey (Christie and Geis 1970), which is the most used survey to measure Machiavellian personality (Liyanagamage and Fernando 2023). It is a 20-question, five-point Likert-type scale self-assessment. The questions are framed to weed out Machiavellian characteristics, such as a cynical mindset from the question, “Anyone who completely trusts anyone else is asking for trouble.” The Machiavellian score was calculated using Rauthmann’s (2013) item scoring method. Participant data was entered into Microsoft Excel to formulate the MACH IV score. Those with scores 60 or higher were considered high Machs (see Fig. 1).

Compared to previous research, this study provides clarity on individual-level Machiavellianism in two ways. The sample includes both low and high Machs (according to the MACH IV survey), to gain a deeper understanding of the Machiavellian continuum. Additionally, instead of following previous research where the participants are classified into high or low Machiavellian according to the MACH IV score, this study openly presents the MACH IV scores of the participants.

Interview Data Collection

Data were collected through face-to-face semistructured interviews and field observations from July to August 2019. An interview protocol was developed based on a priori literature, which included questions about conversations in the construction site. The protocol outlined the interview procedure, including a summary of the study, research aim, ethical and confidentiality procedures, and interview questions. Questions at the beginning asked the participants to describe their position within the firm, and give information about the project, including the timeline, budget, and number of employees working on-site and off-site. Participants were asked about (1) their experience and conversations in the construction site, (2) experiences of communicating with those in positions of power, (3) difficulties experienced in the construction site, (4) communication strategies adapted to deal with the difficulties, and (5) thoughts for improving the communication process in the workplace.

Some interviews were conducted in English (10), and others in the native Sinhala (20) language. As a native Sinhalese speaker, I translated and transcribed all the interviews myself to be close to the data (see Hansen et al. 2022). The interviews conducted in English were transcribed word for word. Incoherent and unclear words were left out of the transcripts. Some participants used a lot of “erm” or constant pauses—these were either written as an ellipsis ‘…’ or removed. Throughout the transcription process, I continued to keep memos of contextual information and nonverbal cues. The translating process from Sinhala to English followed a free translation strategy (Wagner-Tsukamoto 2009), which was the most suitable given the differences in grammatical and syntactical structures between English and Sinhala. Because of the differences in English and Sinhala language, rather than focusing on exact words (i.e., literal translation), free translation was suitable to capture the meanings in conversations. A part of the translation process is interpretation. The words and their meanings in the source text are interpreted in a way that makes sense to the audience (Van Nes et al. 2010). English transcripts were collaboratively reviewed with a native Sinhala speaker fluent in English, comparing them with the original Sinhala transcripts to improve conceptual equivalence. Subsequently, the final English transcripts underwent review by a native English speaker to ensure overall clarity.

Interview Data Analysis

Thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (2012) was employed to analyze the data. Thematic analysis allows one to systematically identify, organize, and offer insights into patterns of meaning in data. This analysis was a hybrid with a combination of inductive and deductive analysis. The inductive was “driven by what is in the data” (Braun and Clarke 2012) and deductive coding through drawing on elements of conversation (Bakhtin 1981; Cunliffe and Eriksen 2011) and employee voice (Erkutlu and Chafra 2019). Initially, I read through the interview transcripts and listened to the audio recordings, from an analytical and critical mindset. I also drew on my observations during data collection. As the thematic analysis process evolved, I reread all the data to review the meaningfulness, coherence, boundaries, and quality of the themes. Several patterns were noted related to conversations, including dialogic and monologic conversations, active listening, employee voice, and employee silence. A codebook (Table 2) was developed to guide the analysis.

| Themes | Example interview excerpt |

|---|---|

| Leaders’ communication strategies | |

| Monologic conversations | “I have to convince the junior staff [and laborers] …” Brian. |

| “[Good leadership is] like a tree… information going through [branches] and it’s controlled by each manager” Paul. | |

| Dialogic conversations | “If there’s a problem in the site, they’ll tell me, and we will discuss it like friends and get an answer” Travis. |

| “I don’t say, ‘I’ did this… I say that ‘we’ did. I haven’t used the word ‘I’ because an individual cannot do anything” Tony. | |

| Active listening | “As a leader I’m listening to them [staff] first, I’m listening to them, and I try to get their idea and the decisions” Ian. |

| “We are open, we don’t isolate ourselves. So, the employees can approach us directly. We don’t want to create layers” Tony. | |

| Dialogue to unify meaning | “I always tell the client and the consultant that we’re not your enemy… we’re cooperating with them beyond the limit” Uday. |

| “That’s why we discuss with each and every person about what we’re going to do, what we will do. We discuss everything and share our knowledge…” Rachel. | |

| Leader (opportunistic) silence | “I’m telling them this is a loss [making] project… [because if] They’re thinking this is profit[able]… they will try to relax…” Ian. |

| “Rather than sharing it with someone, I like to have full responsibility on me. That’s easier… Then all the decisions that I take, I can decide rather than getting advice or waiting for someone” Stuart. | |

| Employees’ voice | |

| Employee voice | “[The boss] doesn’t have much experience as we have, and that is, the truth…” Scott. |

| “[T]hey put [so much] pressure on me… it makes me angry… There have been numerous times when I’ve argued with my boss…” Patrick. | |

| Employee silence | “Over here laborers can’t talk to the top. When you look at the office, there are glass rooms, and the bosses are in those rooms… Honestly, we’re scared to. Because we don’t know what sort of response we’ll receive” Vivian. |

To offer depth to the findings, following the data analysis, the participants were classified based on their leadership role. For this, I drew on social identity theory (DeRue and Ashford 2010), particularly the concepts of claiming and granting. Participants in positions of authority were claiming their identity as a leader, and their subordinate employees were leading conversations that grant those in positions of authority the identity of a leader. For instance, when Ian notes “As a leader, I’m listening to them [staff]” he was claiming himself the identity of a leader. The process of claiming and granting can be verbal or nonverbal and direct or indirect, such as manipulating artefacts linked with leadership. Likewise, other employees in the workplace granted Ian the “leader” identity through their choice of language (i.e., ‘leader’, ‘boss’, ‘sir’). I followed this process for all the construction sites, and Table 1 classifies individuals claimed and granted the identity of leader as “leader” and individuals in subordinate positions as “employee.” Some construction sites (i.e., 3 and 5) have more than one leader.

Findings

This interviews with leaders and employees in the construction industry are presented below. Leadership role of the participant and their MACH IV score is presented in parentheses, for example, Uday (leader, 70).

Theme 1: Monologic Communication Strategies with Machiavellian Intentions

Communication is critical, especially in construction firms where the success of a project is in the hands of various stakeholders working together toward the same outcome. In such environments, leaders tend to form relationships with selected individuals with direct influence over the construction project, for instrumental motives (Boyatzis et al. 2014). Uday (leader, 70) explains “I’m not the one who does everything here, because I’m not superman… [because] I cannot go ahead without the consultant’s support. To get their support we must have a good relationship…” However, stakeholders with influence on the project were receiving preferential treatment. Interviews suggest that the difference in status between engineers and laborers has formed an “us” versus “them” mentality, impacting their communication and relationship. Ian (leader, 60) explains that laborers are different, that they are uneducated and irresponsible, causing him to engage monologic communication strategies.

If you tell a laborer to come at 5.45 am, they won’t. We have to tell them two-three times. That’s the difference of a laborer. [They don’t understand] responsibility, they’re not thinking about time or work… so when we are working with them, we have to consider those things and manage them. Tell them that “you have to do this work, within this time frame”…

Similar monologic communication strategies were also noticed in spaces that were meant for knowledge sharing. Typically, construction sites have planned meetings in the morning, often termed “pre-start” or “toolbox” to discuss the daily schedule. These spaces provide opportunity for back and forth communication on how to tackle issues and create cross-team communication between different teams.

When I discuss the project with staff, I put the problem on the table, [I say] “I’m being very frank with you, I’m being very open now, if you have anything to say, tell me to my face, [but] don’t tell it here and there. If you have anything to say, tell me now. We can find a solution, if you think we have a better solution, tell us in the open, so it will be good for others too.” That is how I corporate with these people and coordinate, I think they are happy.

Uday (leader, 70) was rather threatening when he said, “tell me to my face.” My observations directed that Uday was perhaps frustrated at his staff for not openly and honestly communicating with him during the meeting and engaging in indirect vexatious claims instead. Although Uday’s language in the pre-start was not necessarily monologic, the tone and intensity expressed the need to control the conversation and a sense of distrust in the employees.

Interestingly, Paul (employee, 46), a 26-year-old planning engineer explains that “[Good leadership is] like a tree… information going through [branches] and it’s controlled by each leader.” Paul’s perspective recognizes that leadership should include communication channels, but also the control of information. According to the MACH IV survey, Paul would be classified as a low Mach, which further adds to the surprising nature of the finding that low Machs may share similar characteristics to high Machs. Likewise, Piyal (employee, 51), a 51-year-old masonry tradesman with no formal education, acknowledges the use of controlled information and deception in conversation. In Piyal’s perspective, the use of deception was not for harm, but to establish whether his colleagues are ‘honest’ or ‘trying to cheat.’

Different people have different perceptions… when I go to a workplace to build a relationship with a person, I figure out if a person can work or not. Not by their work, but by their perceptions. When I work with them, I can get to know…if he’s an honest man. But if he has deception in his mind, it will come out when he talks… [If] they’re not honest, [then] they’re trying to cheat. They’re not trying to build properly or beautifully; they’re trying to get the money. There are people like that, but people like that are easily caught.

Piyal relies on conversations to understand people and their differing perceptions and engage in conversations as a deceptive tool to uncover others’ immoral or dishonest discernments. However, Piyal believed that the cause was justifiable. These perspectives suggest that perhaps Piyal’s distrusting nature manifests in conversations, where he tries to ‘out’ them for their dishonesty.

Theme 2: Self-Proclaimed Active Listeners

Ian (leader, 60) explains the importance of listening in leadership, and to developing relationships.

As a leader I’m listening to them [staff] first, I’m listening to them, and I try to get their idea and decisions. I’m not showing them that I’m the person and only I can take decisions at this workplace. The team has [to take] decisions, I want to show them that this is a team decision. Finally, my decision is [implemented], but I’m asking them.

This account explains the deceptive nature of conversations. Ian agrees that employees should be listened to, and they should feel included in the conversations leading to decision making in the workplace. Nevertheless, Ian only creates such a context for ‘show’ and retains control of the final decision. In Ian’s perspective the subordinates would feel included in the conversation. Despite Ian’s strategies, some employees feel heard. For instance, Travis (employee, 71) explains that “Actually, he [Ian] is like an elder brother to me. Not to that extent but he always instructs me and even about personal matters…most of the time, I listen to him.” It is interesting to observe that the dynamic between Ian and Travis may stem from Travis actively listening to Ian, rather than the reverse.

In contrast, other employees feel unheard and neglected by the leadership. Anton (employee, 63) has informed the leadership about experiencing problems in the workplace, and “spoken up about them in meetings.” Anton has made this decision knowing that it may “backfire” given that their jobs are on a contractual basis, with those in positions of authority having firing power. Similarly, Vivian (employee, 49) expresses feeling fearful about approaching Ian, citing uncertainty about his potential response. She perceives a clear distinction between them, emphasizing his role as the “boss” situated in a “glass room,” in contrast to her outdoor office space. Therefore, she explains that she prefers to remain silent rather than voice her views. In contrast, Anthony (employee, 47) believes that employees should accept the leaders’ wishes, which he compares to a father-son relationship.

We do what our father tells us, or we should leave home… Even with [Lance] it’s like that, if you can’t work with the people he assigns, might as well leave. I would probably say the same, ‘if you can’t handle it, then leave.’ There’s no point in creating problems for no reason.

Theme 3: Pseudodialogic Conversations with the Intention to “Unify” Meanings

Mutual understanding is crucial for construction site teams. If team leaders or members are misunderstood, it can create a ripple effect of issues that might breach health and safety protocols or result in an injury. Some leaders attempt to cultivate a mutual relationship by unifying dialogue to achieve synchronized communication with the employees. For instance, Scott (employee, 61) explains that the team communication styles need to work together—they should share a mutual understanding of the situation in a construction site: “I have to build a friendly relationship with the helper… helper has to understand me, and I have to understand the helper.” As Scott explains, leaders need to communicate clearly, and the leader and team members should be willing to actively listen and respond openly and honestly. Unified conversations are crucial where people from different cultural, ethnic, religious, or socioeconomic backgrounds work together to complete one project. According to Tod (leader, 58), a supervisor in a medium-sized construction project, conversations leading to shared meaning is an ongoing journey.

Different people have different perspectives. It is impossible to figure out a person straightaway, [but] with time and by communicating…it’s possible to figure out a person’s tolerance, their skills, what jobs will be good for them if I wanted to speak to them how I should speak to them.

Communication can be in verbal or written form. Likewise, Stuart (leader, 46), a project manager of a large-scale construction site, reported to writing letters to their client, however for a self-serving reason.

For this project we have already written 250 letters [to the clients] … that relationship was very, very useful… [when a financial mistake happened] because they understood, they knew we are trustworthy contractors and we won’t misuse [them]… that way, when they found a mistake [they believed it to be a] genuine mistake, and they accepted.

Stuart strives to engage in continued dialogue with the clients, to build a relationship that is instrumental in nature, so when or if they make a mistake, then the client would be lenient toward them because of the existing relationship. Bernard (employee, 50) explains that Stuart creates an environment that plays a significant role in the employees’ acceptance of Stuart’s instructions.

If we are asked to do something, we can’t say no to that because it’s the way [Stuart] does things, we can’t say no. Most of the time we are doing it anyways because he is not forcing us. He ensures that the message conveyed correctly, so we know it’s our job, and we do it without hesitation… He gives us respect, so we do the job.

Bernard’s account further conveys Stuart’s ability to manipulate relationships through monologic conversations that appears to be dialogic in nature. Furthermore, during our conversation, Stuart mentioned enjoying making independent decisions without consulting fellow employees.

Rather than sharing it with someone, I like to have full responsibility for myself. That’s easier… Then, I feel like I’m a responsible person. Then all the decisions that I take, I can decide rather than getting advice or waiting for someone.

The interview conversations further unearthed other monologic conversations that appears to be dialogic, especially between staff members (“us”) and laborers (“them”). Often, people at the bottom of the hierarchy (that is, laborer’s) are not privy to the important decision-making dialogues that occur in staff meetings. The conversations held with laborers are mostly monologic, that is, the supervisor tells the laborer what to do. In this study, the dialogue that occurred between the office staff was not accessible to the laborer’s, thus causing conflict between staff and laborers. To bridge the gap in access to information that exists between staff and laborers, engineer Brian (employee, 61) states to engage in dialogic conversations to unify meaning.

I have to convince the junior staff [and laborers] because sometimes people on site might not know the whole story. Because they don’t overhear what we decide [off-site], so sometimes I have a chat with them to explain why we took a certain decision. This is why so and so took this decision, so please don’t get upset, we will follow this decision, even though we did something different last time, I remind them that next time we might do something entirely different, don’t expect to do the same thing again and keep them on their toes.

While recognizing the diverse voices of the laborers, Brian attempts to impose the managerial voice on them through monologic conversations, by seeking to convince and explain. Although engaging in dialogue with the laborers, Brian’s approach comprises of both monologic, where managerial views are forced on the laborers, and dialogic involving back and forth conversations with the laborers.

Discussion

This research stands out as one of the few studies exploring “ineffective” or “toxic” forms of leadership, specifically within the construction industry, presenting several contributions to the existing literature.

First, this study contributes to research on leadership in the construction industry, and particularly extends previous research on Machiavellianism to explore how Machiavellian behaviors are manifested in leaders’ communication strategies. The findings of this study suggest that high Mach leaders employ nuanced communication strategies that encompass both monologic (manipulate or convince you to agree with my point of view) and dialogic (fostering new possibilities while acknowledging differences) elements. These high Mach leaders strategically control meanings and impressions through their conversations, yet simultaneously engage in reciprocal dialogues with employees.

Notably, their communication strategies adapt based on factors such as the educational background, organizational position, and socioeconomic status of the involved employees. The interview accounts shed light on high Mach leaders initiating dialogic conversations with clients, site engineers, and office staff, treating them as equals. In contrast, their interactions with laborers predominantly involve monologic conversations, possibly serving as a means of exerting control. These differences in communication strategies may also be influenced by cultural elements, especially those related to socioeconomic discrimination rooted in material resources (such as education, income, and occupational prestige) and caste systems, which allow the dehumanization of people. Individuals from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, often engineers and project managers, may believe it is acceptable to perceive those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, typically laborers and site workers, as “other,” “them,” and “less than” themselves.

Nevertheless, high Mach leaders seem to value forming and sustaining relationships with some stakeholders and so, they engage in active listening. Insights gained from interviews with high Mach leaders indicate their engagement in conversations with stakeholders as a means to bridge the knowledge gaps existing among different hierarchical groups within the construction site. While these leaders assert that they create conversational opportunities and actively listen, their statements also reveal a desire to maintain a sense of control over the discourse.

The findings further indicate that low Machs adopt a dialogic approach to unify meanings aligned with their self-interest. Accounts from interviews with low Machs highlight their use of communication to bridge knowledge gaps and reconcile differences in perspectives. They recognize the significance of shared meanings within the construction industry, emphasizing its role in minimizing conflicts and fostering an understanding of others’ skills and capabilities. Yet, in contrast to existing literature (Dahling et al. 2009; Nelson and Gilbertson 1991), some low Machs mentioned leveraging communication strategies for deceptive and controlling purposes. These actions may stem from their distrust of others, driven by a desire to protect themselves for self-interest. This behavior, akin to the use of monologic conversations detailed by high Machs, contributes to the evolving discourse in post-heroic leadership studies. It challenges the notion of fixed traits or behaviors attributed to (ineffective) leadership, positioning leadership as a dynamic process. This novel finding challenges the traditional conceptualization of the Machiavellian continuum, particularly the prevailing behaviors associated to low Machs. The distinctiveness of these findings raises the possibility that the behaviors associated with low Mach individuals are context-specific to the construction industry. The high-pressure environment intrinsic to the construction industry might be a catalyst for the manifestation of Machiavellianism in low Mach communication strategies. However, due to the limited literature on Machiavellian communication strategies in the construction industry, as well as in other industries, additional exploration is important to substantiate these assertions.

Second, the study findings contribute to research on the implication of ineffective forms of leadership in the construction industry, on employee voice and employee silence (Brinsfield 2013; Erkutlu and Chafra 2019). The interview narratives highlight that low Mach employees tend to remain silent, while high Mach individuals speak up when they experience unfair, controlling, or manipulative behaviors. The findings suggest that, in the face of workplace dissatisfaction or problems, high Mach individuals are more inclined to voice their grievances compared to low Machs. This propensity of high Machs to speak up may be attributed to their confidence and a strategic approach to opportunistically gain traction, support, organizational status, and control over those in positions of power.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that some employees may genuinely express distress about the workplace culture or welfare, choosing to voice their concerns authentically. The findings further indicate that several low Mach individuals intentionally remain silent to shield themselves from the potential consequences of speaking up, such as termination, diminished contractual rights, or setbacks in promotions (that is, quiescent silence). In the interviews, low Mach employees exhibited a sense of fear toward high Mach leaders. Under these conditions in the long-term, employees’ psychological and emotional well-being may decline, perhaps leading to counterproductive workplace behaviors such as aggression, deviance, revenge, or conflicts, and absenteeism or presenteeism. Moreover, the reluctance to voice concerns about potential workplace hazards can significantly impact the overarching safety culture. Additionally, the concept of respect in Sri Lankan culture may play a pivotal role in employee silence. Traditional expectations of ‘obey your leader’ could normalize toxic leader behaviors, prompting employees to downplay their difficulties (Liyanagamage et al. 2023).

Toward a Framework for Machiavellian Leadership Communication Processes

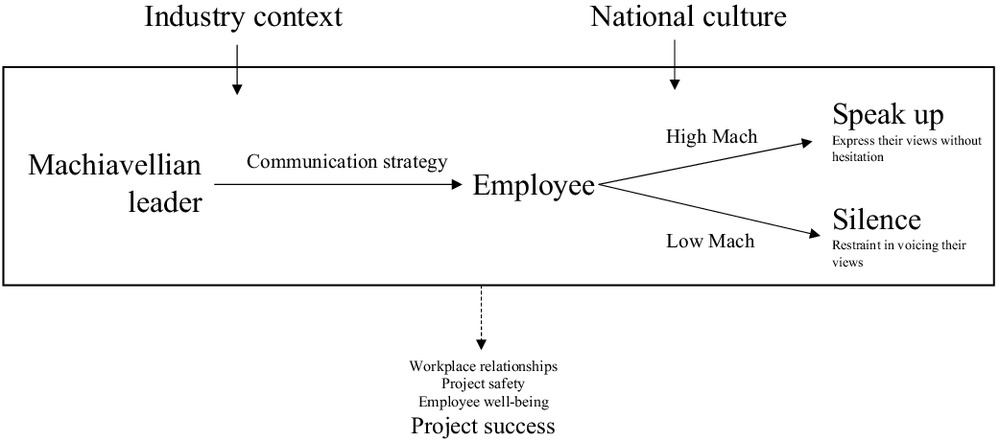

The findings above highlight that various elements influence manifestation of Machiavellianism in leader communication strategies, and its implication on employee voice, in the construction industry. Although these findings are preliminary, they are the first to explore this phenomenon in any context. Fig. 2 is an initial attempt to map the Machiavellian leadership communication processes.

Leader communication strategies are influenced by their Machiavellian personality, industry context (specifically related to the unique nature of the construction industry), and national culture (linked to aspects of respect that contribute to the normalization of toxic behaviors of leaders and socioeconomic discrimination within Southeast Asian culture). These communication strategies, whether monologic, dialogic, or a combination of the two, influence employee voice, depending on employee Machiavellianism. High Mach employees are likely to express their views perhaps due to confidence of self, whereas low Mach employees may restrain from voicing their opinions due to fear and cultural expectations.

Although the primary focus of this research was to explore the communication strategies utilized by Machiavellian leaders and to explore the impact of Machiavellian leadership on employee voice within construction organizations, the findings suggest broader implications. The communication processes identified in the study can have potential consequences for workplace relationships (see Senescu et al. 2013; Cheng et al. 2001), employee well-being (Li et al. 2022; Omer et al. 2022), project safety (see Kines et al. 2010), and ultimately, project success (Jian et al. 2016; Mollaoglu-Korkmaz et al. 2013). Nevertheless, further research is essential to verify and validate these hypotheses, specifically for Machiavellians.

Methodological Implications

The conflicting findings in this study, when compared to previous research on Machiavellians, prompt an inquiry into the potential redundancy of the MACH IV survey in leadership research. The study’s findings underscore the limitations associated with applying the MACH IV survey to Machiavellian leadership research. The survey classifies individuals into extreme categories, suggesting that low Machs are prosocial, caring, and sensitive, while high Machs are distrusting, controlling, manipulative, and hungry for power. However, the interviews in this research highlight the nuances of Machiavellians. They reveal that low Machs can display controlling, manipulative, and distrustful behaviors, while high Machs may exhibit sensitivity and are not consistently inclined toward control or manipulation. Furthermore, the MACH IV survey assesses an individual’s Machiavellianism at a specific moment, overlooking the evolving nature of Machiavellian tendencies across different times and situations in relation to others, viewing it as a dynamic process rather than a fixed trait.

Rather than centering on individual attributes, this question prompts an exploration of which interactions play a crucial role in the expression of Machiavellianism in leader communication strategies. The insights gained from interviews with leaders indicate the utilization of both monologic and dialogic conversation strategies, but these strategies are intricately tied to the dynamics with employees. If a leader ‘claims’ to control, deceive, or manipulate others through conversations, and if the employee participating in the conversation ‘grants’ this authority to the leader, we may observe the manifestation of Machiavellianism in leader communication strategies. Consequently, the manifestation of Machiavellianism in leader communication strategies may hinge on the ongoing processes of claiming and granting of authority within these interactions (Meier and Carroll 2020).

However, if employees ‘resist’ adhering to the controlling, deceptive, and manipulative strategies, the manifestations of Machiavellianism in leader communication strategies may be influenced. Nevertheless, employees may find themselves unable to resist their leaders’ demands, inadvertently allowing the occurrence of Machiavellianism in leader communication strategies. Moreover, this process may operate in reverse, where employees exert control or manipulate leaders or other colleagues through conversations. While these findings are preliminary, they contribute to the argument that Machiavellianism in leadership may be a “socially constructed” process (DeRue and Ashford 2010) that exists not only as a dark trait at an individual level.

Implications for Organizations

The findings suggest that Machiavellianism may impede positive communication, and accordingly, organizations should be attentive and identify when or why Machiavellianism manifests in conversations and promote self-awareness and personality development programs to help individuals understand their Machiavellian inclinations and how it can be harmful to others. This may help the leaders and employees recognize their role in granting and claiming manifestations of Machiavellianism in leadership conversations. Organizations should also create open communication channels and a trusting culture that allows employees to express their feelings and complaints, without fearing backlash or consequences. In addition, the findings of this study indicate that lower-level employees desire communication with higher-level leaders. However, in large-scale projects it may not be feasible to engage in frequent face-to-face communication, accordingly, construction leaders can adapt digital technologies (Rajabi et al. 2022) to create open lines of communication with their employees. Furthermore, the findings suggest that Machiavellianism in leadership is enacted not in a vacuum, but as part of various other elements. Therefore, leaders should not be solely held responsible for negative workplace behaviors. Other individuals, including employees, may be allowing the manifestation of Machiavellianism. All should be encouraged to behave in ways that create a positive organizational culture and promote lasting interpersonal relationships within and outside of the organization. Especially in the construction industry, where there are strong hierarchical separations, all stakeholders (including leaders) must support one another in their journey to achieve project completion.

Conclusion

Existing research has predominantly concentrated on identifying ideal leadership traits, behaviors, and styles for construction leaders, often neglecting the impact of “bad” leadership. Despite evidence suggesting the existence of detrimental outcomes due to bad leadership in the construction industry, research in this area is scarce. This paper addresses this gap by delving into Machiavellian leadership within construction projects, specifically focusing on an Asian context. The primary objectives were to (1) explore the communication strategies employed by Machiavellian leaders, and (2) examine the impact of Machiavellian leadership, as manifested through communication strategies, on employee voice in construction organizations. This research has several novel findings, which contribute to the body of knowledge on toxic leadership communication and leadership in the construction industry.

First, the findings indicate the intricate nature of communication strategies employed by Machiavellian leaders, revealing a dynamic interplay shaped by both leaders and employees. These strategies, which include elements of both monologic and dialogic communication, are tailored to suit employee demographics and cultural norms, incorporating elements of (pseudo-) active listening. Surprisingly, high Mach individuals may exhibit sensitivity and lack consistent inclinations toward control or manipulation, contrasting with previous empirical studies. Second, in contrast to the vast body of literature on Machiavellians, the findings of this study shed light on the capacity for low Mach individuals to exhibit controlling, manipulative, and distrustful behaviors in their communication strategies, a phenomenon potentially influenced by the unique dynamics of the construction industry.

Third, employee voice in organizations with Machiavellian leaders depends on employees’ Machiavellian personality, as well as cultural elements, such as the notion of respect. Ultimately, the Machiavellian communication processes and its implications for employee voice are influenced by various contextual and individual-level elements. Lastly, this communication process may influence critical organizational factors in the construction industry, including employee well-being, workplace relationships, safety culture, and ultimately, the project outcome, whether it leads to success or failure.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

There are several limitations that warrant acknowledgment; however, they also present opportunities for future research. First, this research provides insight into communication strategies of leaders and employees, relying solely on interview accounts. Future research could benefit from real-time observations of interactions between organizational members, encompassing diverse leader-worker and high-low Machiavellian relationships. Additionally, longitudinal ethnographic studies could provide a more comprehensive understanding of how the situational manifestation of Machiavellianism in leadership communication strategies evolves over time. Future research could verify these qualitative interview findings by adopting either a quantitative or mixed-method design, thereby triangulating and enhancing the generalizability of the results. Moreover, future researchers should consider the constraints inherent in the MACH IV survey and investigate individuals across the entire Machiavellian continuum. Second, the generalizability of the research to other geographic regions and industry contexts is limited, and further investigation is necessary to verify these findings in different settings. Finally, due to the male-dominated nature of the construction industry, most of the sample consisted of men. Future research could explore the whether the Machiavellian leaders’ communication strategies differ in female-dominated or less gendered industries, to understand if or how gender influence this process.

Data Availability Statement

The raw interview and survey data used during the study are confidential in nature and may only be provided with restrictions. The restrictions include the use of pseudonyms for participant anonymity, and only the thematically analyzed and coded interview excerpts are provided in the paper.

Acknowledgments

I extend my sincere gratitude to my Ph.D. supervisors, Professor Mario Fernando and Associate Professor Belinda Gibbons, for their support throughout my research journey.

References

Ahmad, R., S. Nauman, and S. Z. Malik. 2022. “Tyrannical leader, Machiavellian follower, work withdrawal, and task performance: Missing links in construction projects.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 148 (7): 04022045. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002290.

Ali, A., H. Wang, M. A. Soomro, and T. Islam. 2020. “Shared leadership and team creativity: Construction industry perspective.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 146 (10): 04020122. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001920.

Assaad, R. H., I. H. El-adaway, M. Hastak, and K. LaScola Needy. 2022. “The COVID-19 pandemic: A catalyst and accelerator for offsite construction technologies.” J. Manage. Eng. 38 (6): 04022062. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0001091.

Bakhtin, M. M. 1981. The dialogical imagination: Four essays. Edited by M. Holquist. Translated by C. Emerson and M. Holquist. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. 2010. Speech genres and other late essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Belschak, F. D., D. N. Den Hartog, and A. H. De Hoogh. 2018. “Angels and demons: The effect of ethical leadership on Machiavellian employees’ work behaviors.” Front. Psychol. 9 (Jun): 1082. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01082.

Belschak, F. D., D. N. Den Hartog, and K. Kalshoven. 2015. “Leading Machiavellians: How to translate Machiavellians’ selfishness into pro-organizational behavior.” J. Manage. 41 (7): 1934–1956. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313484513.

Boyatzis, R. E., K. Rochford, and A. I. Jack. 2014. “Antagonistic neural networks underlying differentiated leadership roles.” Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8 (Mar): 114. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00114.

Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2012. “Thematic analysis.” In Vol. 2 of APA handbook of research methods in psychology, edited by H. Cooper, P. Camic, D. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. Sher, 57–71. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Breevaart, K., and R. E. de Vries. 2021. “Followers’ HEXACO personality traits and preference for charismatic, relationship-oriented, and task-oriented leadership.” J. Bus. Psychol. 36 (2): 253–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09671-6.

Brinsfield, C. T. 2013. “Employee silence motives: Investigation of dimensionality and development of measures.” J. Organ. Behav. 34 (5): 671–697. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1829.

Bryman, A. 2016. Social research methods. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Chan, I. Y., A. M. Liu, and R. Fellows. 2014. “Role of leadership in fostering an innovation climate in construction firms.” J. Manage. Eng. 30 (6): 06014003. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000271.

Cheng, E. W., H. Li, P. E. Love, and Z. Irani. 2001. “Network communication in the construction industry.” Corporate Commun. Int. J. 6 (2): 61–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280110390314.

Cheung, C. M., and R. P. Zhang. 2020. “How organizational support can cultivate a multilevel safety climate in the construction industry.” J. Manage. Eng. 36 (3): 04020014. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000758.

Choi, S., and S. Schnurr. 2014. “Exploring distributed leadership: Solving disagreements and negotiating consensus in a ‘leaderless’ team.” Discourse Stud. 16 (1): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445613508891.

Christie, R. 1970. “Why Machiavelli.” In Studies in Machiavellianism, edited by R. Christie and F. L. Geis, 1–9. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Christie, R., and F. L. Geis. 1970. Studies in Machiavellianism. New York: Academic Press.

Cigularov, K. P., P. Y. Chen, and J. Rosecrance. 2010. “The effects of error management climate and safety communication on safety: A multi-level study.” Accid. Anal. Prev. 42 (5): 1498–1506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2010.01.003.

Cunliffe, A. L., and M. Eriksen. 2011. “Relational leadership.” Hum. Relat. 64 (11): 1425–1449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726711418388.

Dahling, J. J., B. G. Whitaker, and P. E. Levy. 2009. “The development and validation of a new Machiavellianism scale.” J. Manage. 35 (2): 219–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308318618.

Den Hartog, D. N., and F. D. Belschak. 2012. “Work engagement and Machiavellianism in the ethical leadership process.” J. Bus. Ethics 107 (1): 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1296-4.

Denis, J.-L., A. Langley, and V. Sergi. 2012. “Leadership in the plural.” Acad. Manage. Ann. 6 (1): 211–283. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2012.667612.

Dépret, E., and S. T. Fiske. 1993. “Social cognition and power: Some cognitive consequences of social structure as a source of control deprivation.” In Control motivation and social cognition, 176–202. New York: Springer.

DeRue, D. S., and S. J. Ashford. 2010. “Who will lead and who will follow? A social process of leadership identity construction in organizations.” Acad. Manage. Rev. 35 (4): 627–647. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.35.4.zok627.

Detert, J. R., and E. R. Burris. 2007. “Leadership behaviour and employee voice: Is the door really open?” Acad. Manage. J. 50 (4): 869–884. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.26279183.

De Vries, R. E., A. Bakker-Pieper, and W. Oostenveld. 2010. “Leadership= communication? The relations of leaders’ communication styles with leadership styles, knowledge sharing and leadership outcomes.” J. Bus. Psychol. 25 (Sep): 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9140-2.

Edmondson, A. C., M. A. Roberto, and M. D. Watkins. 2003. “A dynamic model of top management team effectiveness: Managing unstructured task streams.” Leadership Q. 14 (3): 297–325.

Erkutlu, H., and J. Chafra. 2019. “Leader’s integrity and employee silence in healthcare organizations.” Leadersh. Health Serv. 32 (3): 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-03-2018-0021.

French, J. R., B. Raven, and D. Cartwright. 1959. “The bases of social power.” In Vol. 7 of Studies in social power, edited by D. Cartwright, 150–167. Ann Arbor, MI: Univ. of Michigan Institute for Social Research.

Geertz, C. 2008. “Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture.” In The cultural geography reader, edited by T. Oakes and P. Price, 41–51. New York: Routledge.

Gemmill, G. R., and W. J. Heisler. 1972. “Machiavellianism as a factor in managerial job strain, job satisfaction, and upward mobility.” Acad. Manage. J. 15 (1): 51–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/254800.

Graham, P., N. Nikolova, and S. Sankaran. 2020. “Tension between leadership archetypes: Systematic review to inform construction research and practice.” J. Manage. Eng. 36 (1): 03119002. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000722.

Hansen, S., E. Too, and T. Le. 2022. “An epistemic context-based decision-making framework for an infrastructure project investment decision in Indonesia.” J. Manage. Eng. 38 (4): 05022008. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0001049.

Harvey, E., P. Waterson, and A. Dainty. 2018. “Beyond ConCA: Rethinking causality and construction accidents.” Appl. Ergon. 73 (Nov): 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2018.06.001.

Hinkin, T. R., and J. B. Tracey. 1994. “Transformational leadership in the hospitality industry.” Hospitality Res. J. 18 (1): 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/109634809401800105.

Hunt, A., K. Walby, and D. Spencer. 2012. Emotions matter: A relational approach to emotions. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Ickes, W., S. Reidhead, and M. Patterson. 1986. “Machiavellianism and self-monitoring: As different as ‘me’ and ‘you’.” Social Cognit. 4 (1): 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1986.4.1.58.

Illankoon, I., V. W. Y. Tam, K. N. Le, and K. Ranadewa. 2019. “Causes of disputes, factors affecting dispute resolution and effective alternative dispute resolution for Sri Lankan construction industry.” Int. J. Construct. Manage. 22 (2): 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2019.1616415.

Imam, H. 2021. “Roles of shared leadership, autonomy, and knowledge sharing in construction project success.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 147 (7): 04021067. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002084.

Jayatilleka, D. 2013. “Machiavelli in Sri Lanka: A response to Prof Carlo.” Accessed January 20, 2020. https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/machiavelli-in-sri-lanka-a-response-to-prof-carlo/.

Jiang, W., Y. Lu, and Y. Le. 2016. “Trust and project success: A twofold perspective between owners and contractors.” J. Manage. Eng. 32 (6): 04016022. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000469.

Keegan, A. E., and D. N. Den Hartog. 2004. “Transformational leadership in a project-based environment: A comparative study of the leadership styles of project managers and line managers.” Int. J. Project Manage. 22 (8): 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2004.05.005.

Khan, N. A., and A. N. Khan. 2022. “Exploring the impact of abusive supervision on employee ‘voice behaviour in Chinese construction industry: A moderated mediation analysis.” Eng. Constr. Archit. Manage. 29 (8): 3051–3071. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-10-2020-0829.

Kines, P., L. P. Andersen, S. Spangenberg, K. L. Mikkelsen, J. Dyreborg, and D. Zohar. 2010. “Improving construction site safety through leader-based verbal safety communication.” J. Saf. Res. 41 (5): 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2010.06.005.

Koo, B., and E. S. Lee. 2022. “The taming of Machiavellians: Differentiated transformational leadership effects on Machiavellians’ organizational commitment and citizenship behavior.” J. Bus. Ethics 178 (1): 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04788-2.

Kwak, W. J., and J. H. Shim. 2017. “Effects of Machiavellian ethical leadership and employee power distance on employee voice.” Social Behav. Personality 45 (9): 1485–1498. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.5896.

Larsson, J., P. E. Eriksson, T. Olofsson, and P. Simonsson. 2015. “Leadership in civil engineering: Effects of project managers’ leadership styles on project performance.” J. Manage. Eng. 31 (6): 04015011. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000367.

Li, K., D. Wang, Z. Sheng, and M. A. Griffin. 2022. “A deep dive into worker psychological well-being in the construction industry: A systematic review and conceptual framework.” J. Manage. Eng. 38 (5): 04022051. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0001074.

Liao, P. C., G. Lei, D. Fang, and W. Liu. 2014. “The relationship between communication and construction safety climate in China.” KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 18 (May): 887–897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-014-0492-4.

Liu, A. M., and I. Y. Chan. 2017. “Understanding the interplay of organizational climate and leadership in construction innovation.” J. Manage. Eng. 33 (5): 04017021. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000521.

Liyanagamage, N., and M. Fernando. 2023. “Machiavellian leadership in organisations: A review of theory and research.” Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 44 (6): 791–811. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2022-0309.

Liyanagamage, N., M. Fernando, and B. Gibbons. 2023. “The emotional Machiavellian: Interactions between leaders and employees.” J. Bus. Ethics 186 (3): 657–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05233-8.

Meier, F., and B. Carroll. 2020. “Making up leaders: Reconfiguring the executive student through profiling, texts and conversations in a leadership development programme.” Hum. Relat. 73 (9): 1226–1248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719858132.

Mesu, J., K. Saunders, and M. van Riemsdijk. 2015. “Transformational leadership and organisational commitment in manufacturing and service small to medium-sized enterprises: The moderating effects of directive and participative leadership.” Personnel Rev. 44 (6): 970–990. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2014-0020.

Michael, J. H., Z. G. Guo, J. K. Wiedenbeck, and C. D. Ray. 2006. “Production supervisor impacts on subordinates’ safety outcomes: An investigation of leader-member exchange and safety communication.” J. Saf. Res. 37 (5): 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2006.06.004.

Milliken, F. J., E. W. Morrison, and P. F. Hewlin. 2003. “An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why.” J. Manage. Stud. 40 (6): 1453–1476. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00387.

Mollaoglu-Korkmaz, S., L. Swarup, and D. Riley. 2013. “Delivering sustainable, high-performance buildings: Influence of project delivery methods on integration and project outcomes.” J. Manage. Eng. 29 (1): 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000114.

Monaghan, C., B. Bizumic, and M. Sellbom. 2016. “The role of Machiavellian views and tactics in psychopathology.” Personality Individual Differ. 94 (May): 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.002.

Nelson, G., and D. Gilbertson. 1991. “Machiavellianism revisited.” J. Bus. Ethics 10 (8): 633–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00382884.

O’Connor, C., and S. Michaels. 2007. “When is dialogue ‘dialogic’?” Hum. Dev. 50 (5): 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1159/000106415.

Ofori, G. 2008. “Leadership for future construction industry: Agenda for authentic leadership.” Int. J. Project Manage. 26 (6): 620–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.09.010.

Olive, C., T. M. O’Connor, and M. S. Mannan. 2006. “Relationship of safety culture and process safety.” J. Hazards Mater. 130 (1–2): 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.07.043.

Omer, M. M., N. A. Mohd-Ezazee, Y. S. Lee, M. S. Rajabi, and R. A. Rahman. 2022. “Constructive and destructive leadership behaviors, skills, styles and traits in BIM-based construction projects.” Buildings 12 (12): 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122068.

Oswald, D., D. D. Ahiaga-Dagbui, F. Sherratt, and S. D. Smith. 2020. “An industry structured for unsafety? An exploration of the cost-safety conundrum in construction project deliver.” Saf. Sci. 122 (Feb): 104535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.104535.

Oswald, D., and H. Lingard. 2019. “Development of a frontline H&S leadership maturity model in the construction industry.” Saf. Sci. 118 (Oct): 674–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.06.005.

Oswald, D., H. Lingard, and R. P. Zhang. 2022. “How transactional and transformational safety leadership behaviours are demonstrated within the construction industry.” Construct. Manage. Econ. 40 (5): 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2022.2053998.

Potter, E. M., T. Egbelakin, R. Phipps, and B. Balaei. 2018. “Emotional intelligence and transformational leadership behaviours of construction project managers.” J. Financ. Manage. Property Constr. 23 (1): 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMPC-01-2017-0004.

Rajabi, M. S., A. R. Radzi, M. Rezaeiashtiani, A. Famili, M. E. Rashidi, and R. A. Rahman. 2022. “Key assessment criteria for organizational BIM capabilities: A cross-regional study.” Buildings 12 (7): 1013. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12071013.

Rauthmann, J. F. 2013. “Investigating the MACH–IV with item response theory and proposing the trimmed MACH.” J. Personality Assess. 95 (4): 388–397.

Senescu, R. R., G. Aranda-Mena, and J. R. Haymaker. 2013. “Relationships between project complexity and communication.” J. Manage. Eng. 29 (2): 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000121.